New Delhi: It is difficult to imagine that something would tie British colonial anthropologists to modern Indian government stamps. But a new exhibition in Delhi shows how British stereotypes about tribal communities have been more or less select-copy-pasted by successive Indian governments in their stamp covers.

In popular imagination, tribals have for long been reduced to a set of iconographic tropes: the exotic, the primitive, the violent, the dancer and one who is close to nature. A new exhibition titled Reframing The Adivasi at the India International Centre Annexe questions this reductive imagery. It brings together a range of cultural material including images of colonial-era museum artifacts, photographs by 19th century anthropologists, lithographs, magazine articles, and commemorative government-of-India postage stamps.

In this provocative visual archive of ‘seeing’, the single takeaway is that the British and the sarkari gaze are similar when it comes to a tribal person.

“We have put together an archive of images to show how the British stereotypes about the Adivasi continue into the post-colonial period,” said co-curator Sangeeta Dasgupta, associate professor of history at the Jawaharlal Nehru University.

“There’s a way in which these stereotypes have been built, replicated, and strengthened over 200 years”.

Even today, state-run tribal museums – from Delhi to Bhopal — continue to exoticise tribal people. They rarely go beyond showcasing their food, huts, bows and arrows, craft and culture, and celebrating them as singing-and-dancing calendar communities. The exhibition, curated by Dasgupta and Azim Premji University professor Vikas Kumar, is an important intervention in these standard representations. It calls out this lazy visual culture that diminishes over 10 crore people of India.

Objects of curiosity

The exhibits reveal the prevailing iconography of tribals from two lenses – British images and independent India’s stamps. These two narrative templates are then broken by a third lens, one of tribal self-representation.

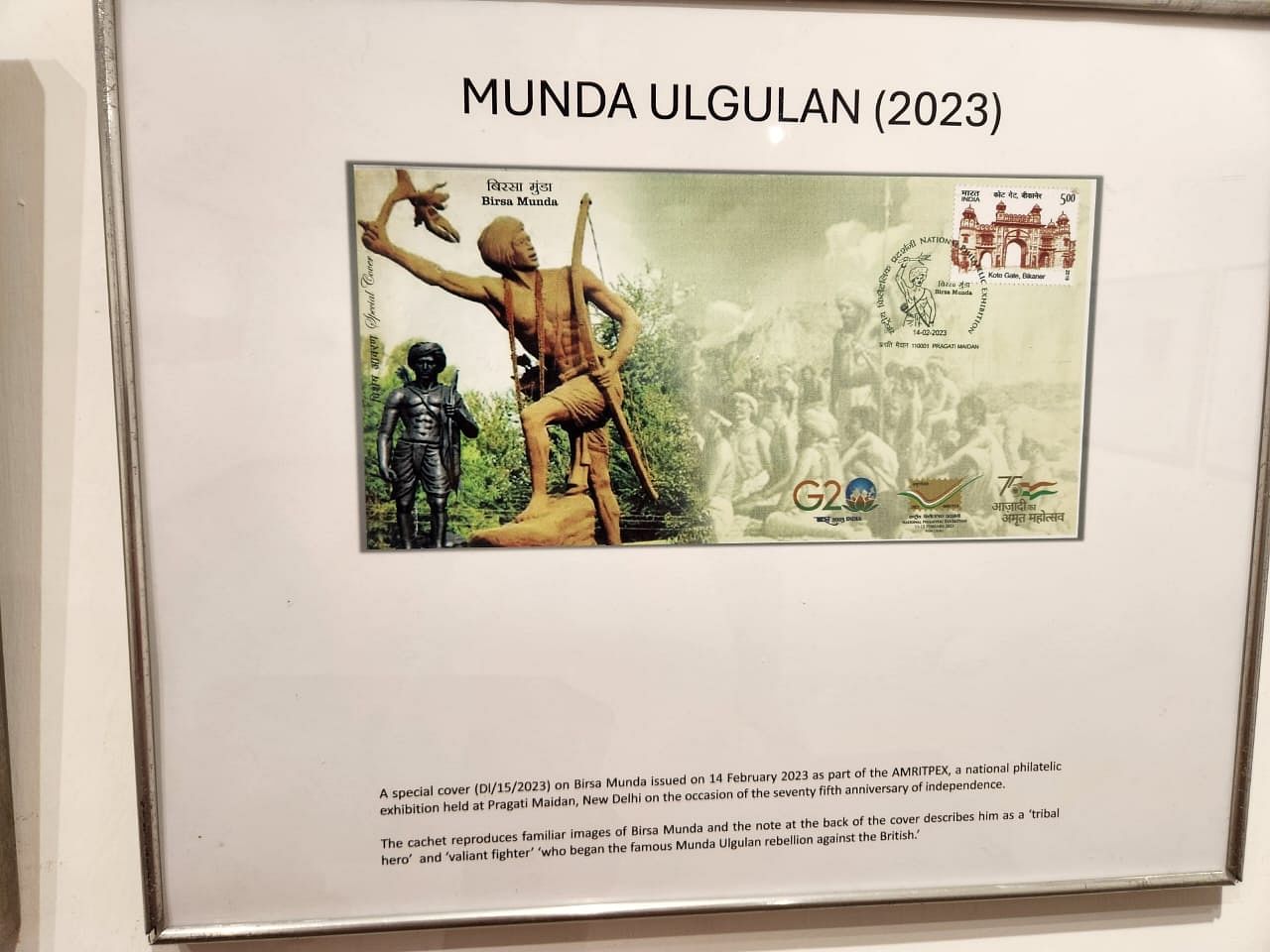

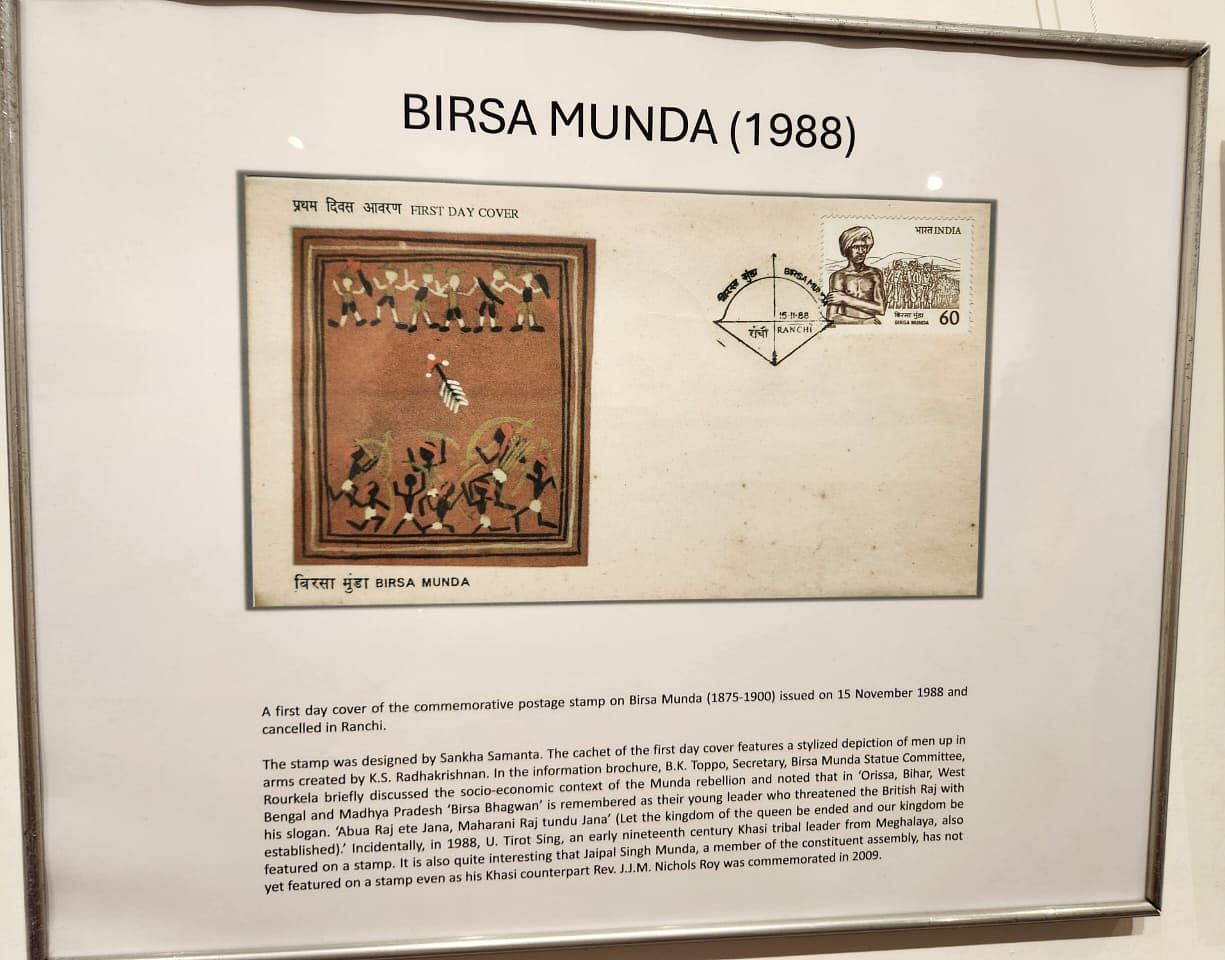

State-produced postal material was circulated across India on a very wide scale, making stamps an important historical artifact. Kumar’s carefully curated postal stamp cover collection featuring India’s tribes was released between 1981 and 2023. These show the tribal male as bare-chested, wearing fancy headgears, feathers and jewels, and often armed – ie., when not dancing. The Tribes of India stamp series shows tribal culture as unchanging, static, and impervious to modern influences. One stamp cover from 2019 even features the GI tag number given to a form of tribal painting.

“The Indian state has to radically rethink the existing modes of engagement with the tribal people,” said Kumar.

The pattern is even older. A stamp from the 1960s was called ‘Nehru and Nagaland’. It shows Nehru wearing a plume hat, holding a spear, and walking ahead of a group of Nagas in traditional clothes. This, however, didn’t make it to the exhibition.

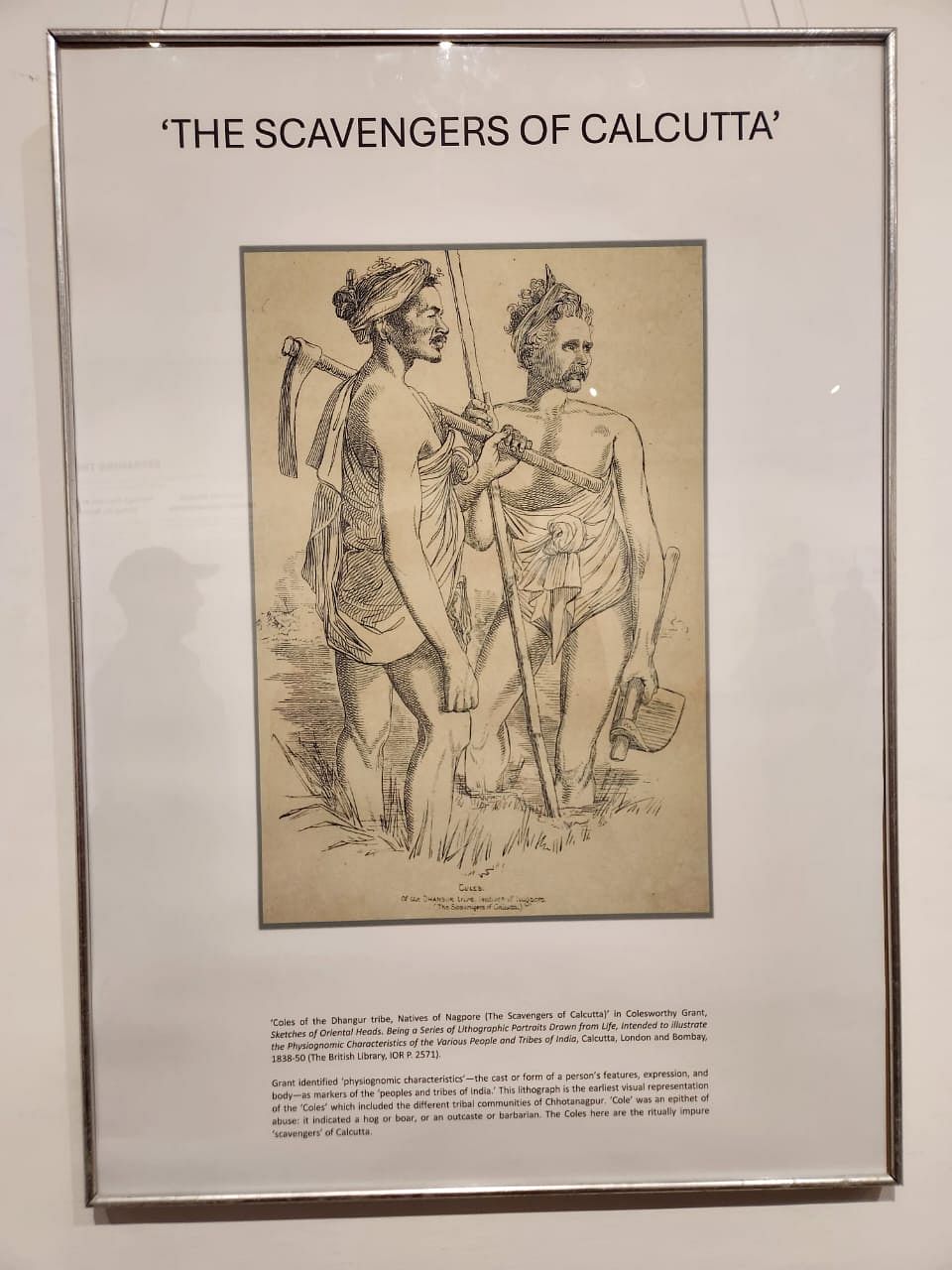

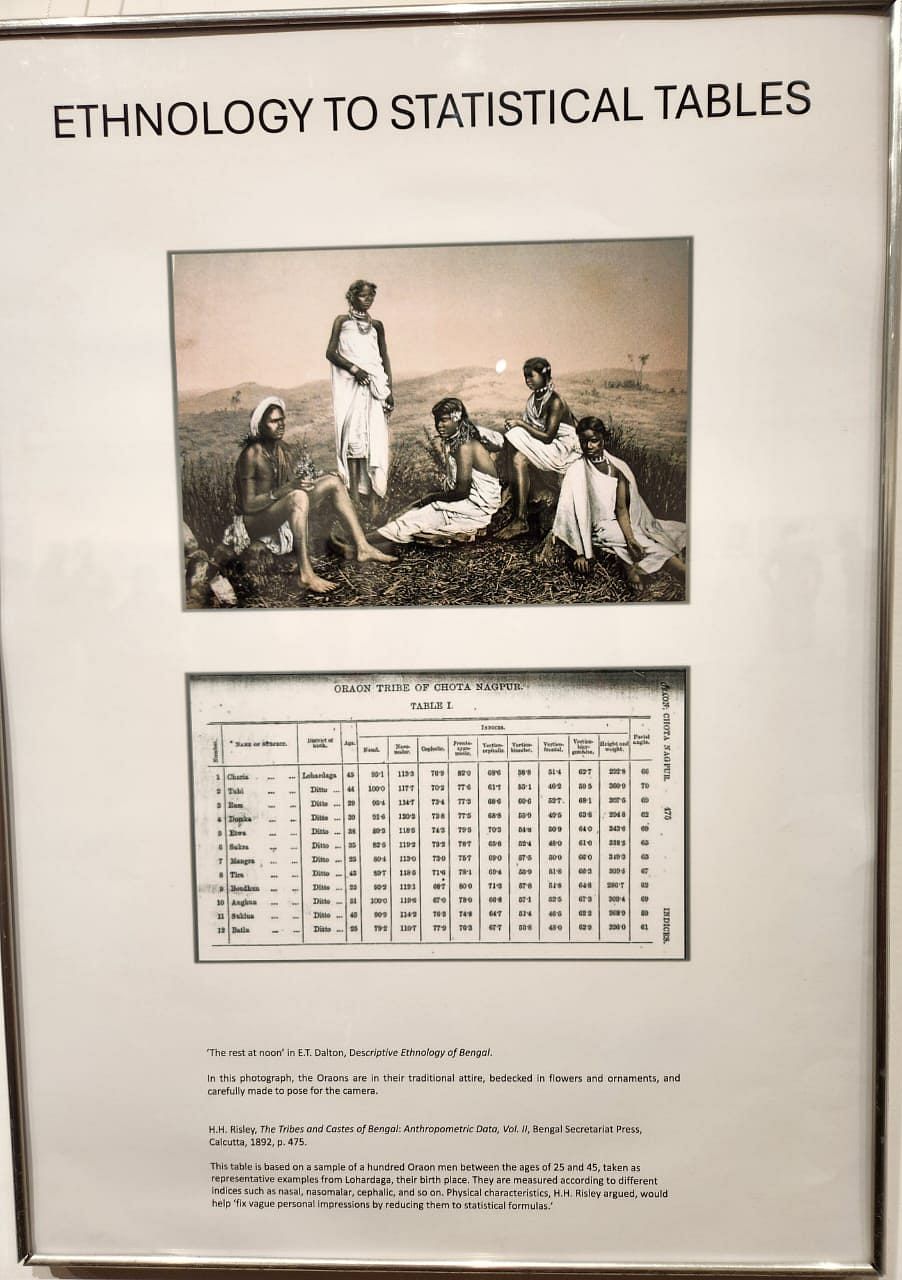

On the other side of the gallery, Dasgupta has curated the images produced by early British anthropologists who drew and photographed tribals as objects of curiosity. Images of the Oraon tribe are set against a table of measurements of their body parts – a pseudo-scientific practice that dominated and guided Western thinking about people from the African continent and Jews.

These measurements were used to serve notions of White racial superiority. Objects belonging to Oraons of Chotanagpur were sent to the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford where they were displayed next to those of Nigerian tribes.

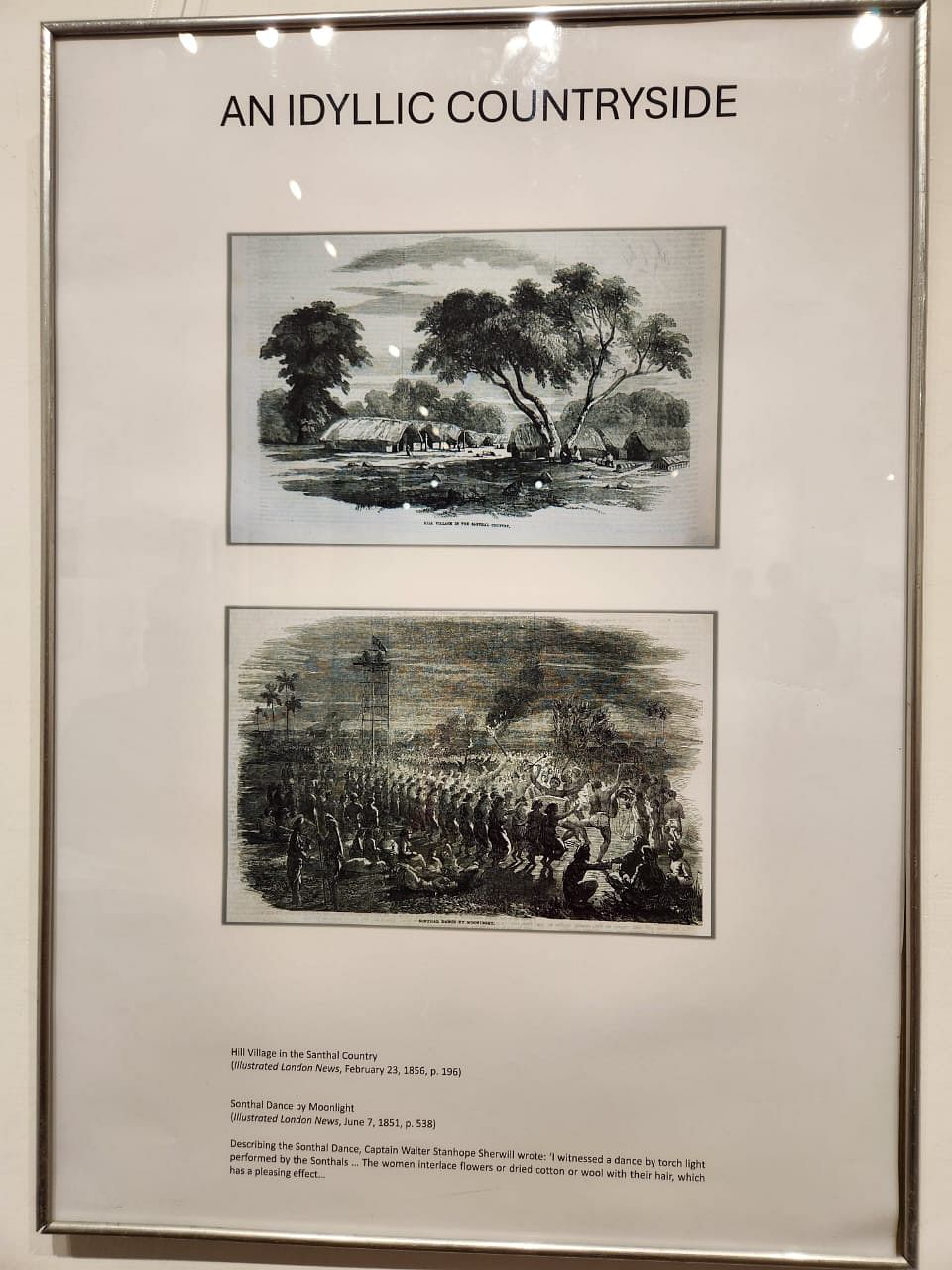

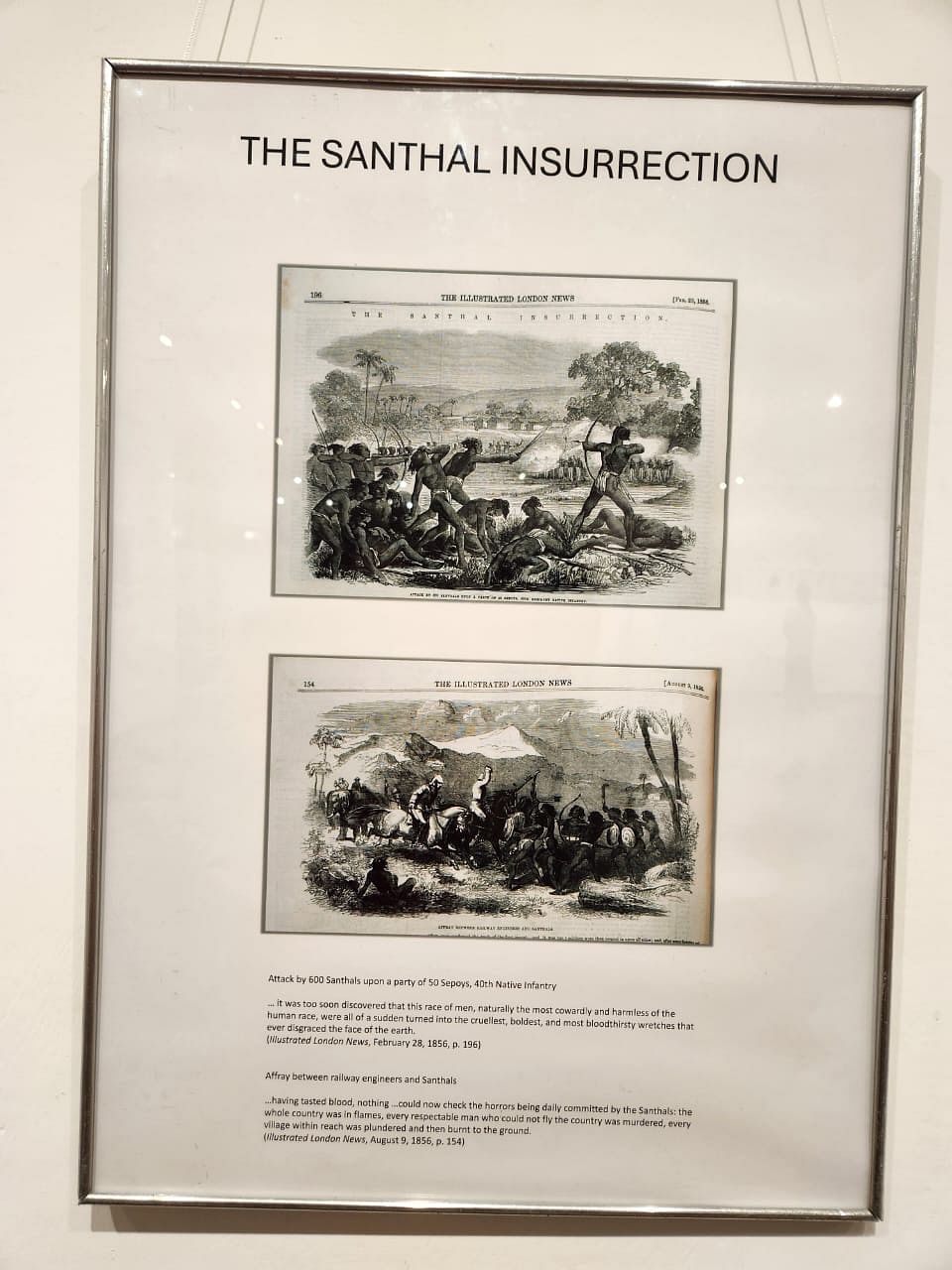

Two images from the Illustrated London News in 1856 and 1851 showed the idyllic countryside of tribal hamlets and their moonlight dances. Another edition from 1856 showed the Santhal Rebellion and the attack on British sepoys. The text in the weekly magazine is chilling: “It was too soon discovered that this race of men, naturally the most cowardly and harmless of the human race, were all of a sudden turned into the cruelest, boldest, and most bloodthirsty wretches that ever disgraced the face of the earth…Having tasted blood, nothing could now check the horrors being daily committed by the Santhals.”

“There are drawings of idyllic countryside and then there is this portrayal of them as absolute savages. It’s as if they are saying ‘we thought they were gentle, innocent, but they erupted suddenly into dangerous, blood-thirsty people’,” said Dasgupta.

“This image of the violent tribal is later co-opted by independent India in its national freedom struggle.”

Also read: What’s missing in the new Humayun Museum of Mughal history? A key decade of India

What’s important

The philately collection sported many stamps on the revolutionary freedom fighters from the tribal community – Birsa Munda, Sido and Kanhu Murmu, Baburao Puleshwar Shedmake, Jatra Bhagat and Budhu Bhagat. One stamp cover in 2017 says the freedom struggle in Jharkhand started much before India’s first war of independence in 1857. Another from 2018 describes the Paika Rebellion against the East India Company rule in 1817.

Birsa Munda features on many stamp covers – from 1988 to 2023. But Kumar said he did not see a single stamp image of Jaipal Singh Munda, the tribal member of India’s Constituent Assembly, an Olympic gold medalist who captained the Indian field hockey team in 1928, and writer.

“The absence of Jaipal Singh Munda from this archive is the most important thing,” he said. “What they show is less important than what they choose not to show. Jaipal Singh did not wear feathers, did not dance for you. He would raise difficult questions about the place and rights of Adivasis in constitutional democracy.”

Also read:

Nothing about us without us

The curators’ subversion occurs in the third section that is sandwiched between the colonial and the philately collections. It is meant to be one of self-representation, foregrounding an adivasi’s own voice in contrast to the other portrayals.

It features Nirmal Minz, a Ranchi theologist, professor, poet, activist and a Bhasha Samman awardee for his work in Kurukh language. His first image is accompanied by his slogan “Garv se kaho hum Adivasi hain” – or “say it with pride that we are Adivasi”.

“It is the polar opposite of the kind of representation you see in history and in the present,” explained Dasgupta.

A line from his poem is exhibited: “The sun has risen, the Kurukh people must rise too”. He had called for the Kurukh to be given recognition in the Eighth Schedule.

“It’s time for adivasis to become real partners in the co-creation of what could be validated and become authentic knowledge,” his daughter, Sonajharia Minz, a professor of Artificial Intelligence at JNU, said at the exhibition. “Nothing about us without us.”

The exhibition is open till 28 August, 2024.

Rama Lakshmi, a museologist and oral historian, is ThePrint’s Opinion and Ground Reports Editor. After working with the Smithsonian Institution and the Missouri History Museum, she set up the ‘Remember Bhopal Museum’ commemorating the Bhopal gas tragedy. She did her graduate program in museum studies and African American civil rights movement at University of Missouri, St Louis. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

thank you for this article.

i think what has been indicated in it is the fundamental challenge when it comes to forming any opinion or judgement about anyone other than your own self (therefore the reason why being opinionated or judgemental regarding others is not a good thing, and can eventually lead to unjust biases and prejudices) which is – what according to your personal opinion or judgement are the characteristics defining another person, is, at the end of the day, but a representation of the image of that person as it has formed inside your own mind, and not necessarily a representation of the image of that person as it exists inside their own mind.

and thus, if one wants to follow the principle of fairness, then one should never feel a sense of certainty about who another person truly is based on their personal opinion or judgement, until and unless they get that opinion or judgement cross-checked and verified by actually talking to that particular person, and asking them about what they think about their own selves.

i guess it is an important idea behind the need to have a fair and impartial judicial system in any society as well.

thanks again.