New Delhi: Qawwalis from Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya dargah have echoed through Nizamuddin’s gullies for centuries, but in a dimly lit alley on a chilly night, another sound took over. A group of young men slapped their palms against their thighs, building up a beat and rhythm. Then, Umaid ‘Pablo’ Abbas closed his eyes and launched into an Urdu-driven rap song. His voice was raw and his words had nothing to do with the Chishti saint.

“Dhokebaaz log, dogle yaar hai ye log,

Dass lenge sanp banke ye, aese yaar hai ye log,

Bante paak sanf bahaut, nasha kare haram,

Kaam kare bina inhe chahiye inaam,

Inhe doon mein sudhar, ye gana likh kar.

Inhe doon mein sudhar inke baap bann kar.”

Traitors, two faced-people,

They’ll strike like snakes while pretending to be saints.

These guys act pure, but it’s all fake.

They’re deep into drugs, doing wrong, yet want rewards…

I’ll set them straight with this song. I’ll show them who’s boss.

Abbas’s friend Rehan ‘MC Error’ Khan nodded along, then jumped in. Kids playing nearby stopped to listen. Some neighbours love it, others roll their eyes, saying this isn’t what Nizamuddin stands for. But for these rappers, it’s a way to be heard—and a way to give back.

“We’ve seen pain, we’ve seen hunger, we’ve seen doors shut in our faces. But rap lets us turn all of that into something powerful,” said 20-year-old Khan. “I want to represent Nizamuddin through my rap. I want to add to its name.”

For the past 700 years, Nizamuddin has been known for its qawwali and the Sufi traditions of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya. But in the its narrow lanes, basti rappers are creating something new. Their mausiqi (music) isn’t about saints or shrines. It’s about a city that overlooks them, a system that leaves them behind, and the struggle to survive. It’s also about love, betrayal, friendship, hope, and the need to connect with the wider world.

They take inspiration from Sufi culture but aren’t bound by it. Qawwali has long crossed over into other genres, from Kun Faya Kun in Rockstar (2011) to the many Coke Studio renditions of mystic poet-musician Amir Khusrau’s Aaj Rang Hai. These basti rappers are pushing it even further.

“Qawwali doesn’t let us say what we want to say. The things we write, we can’t express them through qawwali. Rap gives us that space,” said 24-year-old Abbas.

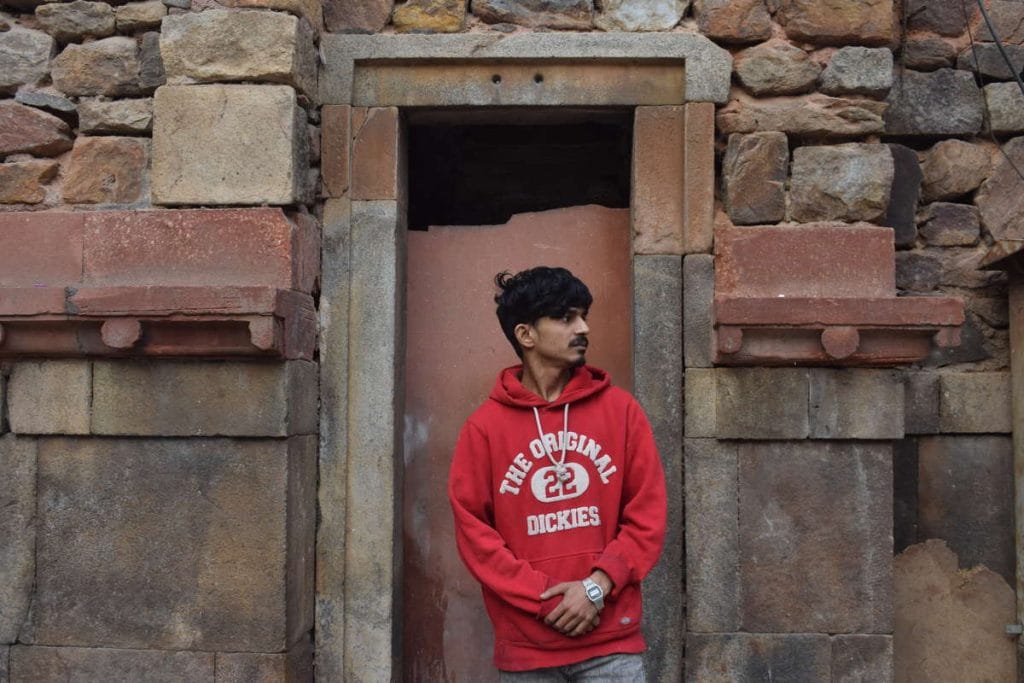

By day, Abbas sells momos and chowmein at his stall. He’s shy and softspoken with a disarming smile. But as the sun sets, he embraces his identity as Pablo, carefully selecting his signature hoodies and chains. When it’s time to perform, he gathers his energy, raising his voice with purpose and passion.

Poverty limits opportunities for men like Abbas and Khan, but smartphones bring the world closer. They watch Mumbai’s gully rap scene, follow global hip-hop trends, and share their music on Instagram and YouTube. One viral clip can turn a local rapper into a name beyond the basti.

With exposure to social media and international trends, young people are remixing tradition and creating fresh forms of expression, according to Azra Abidi, head of the Department of Sociology at Jamia Millia Islamia.

“Young people feel the need to understand the true essence of music. That’s why they’re experimenting and even trying to create their own version of Sufi music infused with innovative ideas,” she said.

And then there is catharsis. For Abbas, rap started as a response to personal heartbreak and the frustrations of daily life.

“I picked up the pen when I felt like no one was listening,” he said. “When I rap, it’s like I’m reclaiming my voice.”

Also Read: Sufi saints and Sultans in Delhi—a delicate balance of asceticism and politics

Rap as an escape

It’s the gritty gangsta life, and the pin code is Delhi-13. Young men prowl in dark streets, between desolate buildings, under a sprawling banyan tree. Over a thumping beat with sharp, looping rhythms, MC Error locks eyes with the camera and spits lyrics about loyalty, locality, and lawlessness:

“Dilli 13 mein kaale kaale kaand kare humne;

Dilli 13 mein kaale kaale daag lage apne

Dilli 13 ke toh chhod doon main kaise…

Saare dagabaaz nikle, koi paas na aaya.

Dilli 13, mere saath uska hi saaya.”

We did dark, dark deeds in Delhi-13.

Dark, dark stains have marked us in Delhi-13.

How can I leave Delhi-13?…

Everyone betrayed me, no one stayed close.

Delhi-13, you’re my only refuge.

This is the music video of ‘Dilli 13’, Rehan Khan’s latest YouTube release—his homage to the streets where he grew up.

“I’ve spent my whole life—my 20 years—here. My basti is everything,” he said. “This place is my heart. I’ll never leave.”

For the last four and a half years, hip-hop has been his outlet. In 2020, as Delhi shut down, Khan’s household income vanished . His family was struggling, and at the same time, friends he trusted turned their backs on him. Heartbreak, isolation, and frustration piled up. Rap became his escape, a way to turn pain into poetry.

“I couldn’t trust anyone; I started facing mental health issues. Nobody understood me. I had no one, so I started writing rap,” he said.

His stage name, MC Error, is a reminder of some of the choices he regrets, but he shrugs: “Every mistake is a lesson.”

Khan made it to high school, but the school never felt like it was meant for him. Teachers talked about history and math, but nobody talked about the struggles outside the classroom.

With nothing but a phone and a need to be heard, he started his YouTube channel in 2020. What began as an outlet started giving him a sense of purpose. He now calls himself a “people’s poet.”

He has no sponsors, no record labels, and builds his sound with whatever resources he can gather. His YouTube channel has only 124 subscribers, but ‘Dilli 13’ has over 1,200 views since its release in January. He’s getting somewhere, even if slowly. And he’s found a tribe—young men in the basti who look up to him, who see their own stories in his words.

Mahaul, mausiqui, and mentorship

The quiet lanes near Mirza Ghalib’s Haveli have become an unlikely stage, where basti rap is edging out traditional mausiqi. Open terraces, empty courtyards, and narrow alleyways now double as impromptu performance spaces for young rappers.

Rehan Khan has become a leader among them. His ambitions go beyond rapping—he wants to put Nizamuddin on the map through hip-hop to show that even from the narrow lanes of the Basti, powerful voices can rise. He hopes to mentor young artists, set up a proper recording space, and one day perform on a bigger stage beyond Delhi.

“I want to make my family proud,” he said.

His parents, once sceptical, have come around. Seeing his dedication, they’ve started supporting his craft—buying him better headphones, a mic, and a secondhand laptop. What once seemed like a distraction has now become a source of pride.

“As long as he’s doing something productive, we’re happy,” his father said.

Khan’s music has inspired others in the basti. His neighbour Rider, also known as Saad Ali, had given up rapping for four or five years, focusing instead on his work at a mirror and glass-cutting shop. But after watching Khan and other local rappers, he’s finding his way back.

“It was these brothers who helped me get back on track with my music,” Ali said.

Among those Khan has influenced is Umaid Abbas, who started rapping only six months ago but is now passionate about it.

Originally from Amroha, Uttar Pradesh, Abbas comes from a migrant family. His father, a tailor, moved to Nizamuddin Basti in search of a better life but struggled to make ends meet. Abbas had always been drawn to hip-hop, but it was Khan who pushed him to take it seriously—encouraging him to rap during late-night jam sessions, helping him refine his flow, even co-writing some of his early verses. Their bond has grown through music, with hours spent crafting lyrics together.

“Music is my lifeline, and my pen offers me redemption,” Abbas said. “When no one listened, my pen became my voice.”

Their rehearsal spaces are the open spaces of the city—Sunder Nursery, Humayun’s Tomb, the basti’s gullies, under the arches of Barakhamba. With a phone playing a beat and a notebook filled with hurried scribbles, they practice wherever they can, without a mic or speakers.

When he’s not working on his music, Abbas runs an Indo-Chinese food stall, which he started with his brother 7 years ago. He now lives in a home he built himself after years of renting. His journey hasn’t been easy, but he’s determined. One of his songs speaks of perseverance itself as an achievement:

“Mehnat hai jaari, abhi to bohat kuch hai baaki.

Mehnat karta rahun, meri yahi hai kamyabi.”

Hard work continues; much remains to be done.

I keep persevering, that is my true success.

Writing alongside his ‘brothers’—his fellow basti rappers—Abbas captures life in the margins, turning shared experiences into punchy verses. Under a tunnel in Nizamuddin, he spontaneously broke into a rap:

“Akela hi sahi, uss rab ki thi marzi.

Karte hain ye waar, peeth peeche yaar.

Inhe nahi pata, poori planning hai tayyar.

Mere yaar thoda ho ja hoshiyar, warna mai kaam daal doon raaton raat.”

Even if I’m alone, it’s fine, for it was the will of the Divine.

They strike blows, behind my back, these friends.

They don’t know, I’ve got a whole plan ready.

My friend, be a little cautious, or I’ll get the work done overnight.

This was his first song, inspired by a friend’s betrayal. Though there’s no video, the track has earned him respect among friends.

“Through my rap, I shared my truth with the world. For the first time, the people in my basti truly saw me—and they showed love like I’d never felt before,” he said with quiet pride.

Sufi influence and new sounds

With his winged locks, Instagram reels featuring swanky cars, and cigarettes in hand, Abbas doesn’t look like someone shaped by Nizamuddin’s spiritual culture. But he insists his passion for rap is rooted in the basti’s Sufi traditions.

“It is all an influence from Dilli 13,” he said. “Every corner has a story.”

Both Abbas and Khan remain deeply connected to the spiritual essence of Nizamuddin. Growing up near the dargah, they were immersed in Sufi poetry, qawwalis, and the teachings of Amir Khusrau, which shaped their understanding of music and storytelling.

“Sufism teaches us to express the deepest emotions—love, pain, and longing. That’s what we do with rap,” said Khan. “The only difference is that we talk about today’s struggles.”

For them, hip-hop is a modern form of Sufi expression, where beats replace the rhythm of qawwali, but the essence remains the same. Just as Sufi poets questioned authority, spoke for the oppressed, and searched for truth, their rap challenges social injustice, betrayal, and survival in the streets of Delhi.

“Our words, like Sufi verses, come straight from the heart,” Abbas added. “Instead of singing in the dargah, we rap in the gullies.”

Though Abbas finds solace in qawwali and writes primarily in Urdu to stay true to his roots, rap is the musical language he connects with the most.

“Qawwals, for all their beauty, often focus on devotion rather than personal emotions,” he said.

While Khan respects the qawwali tradition, he sees hip-hop as the sound of their generation.

“Qawwali will always have its place, but desi hip-hop is the voice of today,” he argued.

As Sufi music meets the rebellious rhythms of hip-hop, it challenges the community to redefine its musical identity. Some see it as a natural evolution, a fusion of old and new that speaks to resilience and reinvention.

Qawwal Sultan Niyazi, one of the renowned Niyazi Brothers who mesmerises audiences weekly at Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, is open to the change.

“Qawwali is soulful music and rap is a form of entertainment. But they are both some form of music,” Niyazi said. “Music moves the heart and if someone derives peace from music, then let them pursue it.”

But not everyone is thrilled about it. For some, rap is just noise.

“This new culture is absurd. The basti is renowned for its dargah, Sufi traditions, and qawwali. Why are these youngsters ruining it?” said Rubeena, a Nizamuddin resident.

Yet rap is no adversary to Sufi music. Scholar Abidi argues that the Sufi ethos of peace, inclusivity, and “inherited spirituality” will always draw people in and has room for everyone.

“We are living in a plural society which is based on the idea of coexistence… and every religion, especially Sufism, teaches us this idea of coexistence,” she said.

In most of their songs, Khan and Abbas keep circling back to the basti and their lived experiences, but now and then, bigger dreams glimmer through.

In his song Zikar, Khan raps about lost innocence and heartbreak, but ends on a promise to himself: “Mushkilon se saari, main sambhalta rahunga. Haan, ek din main bhi jana, star banunga”—I’ll handle all the difficulties. Yes, one day I’ll become a star.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)