New Delhi: The history war of the past decade has largely split India’s past into a glorious ancient Hindu era, followed by a dark period of around 1,000 years, marked by endless cycles of invasion and conversion.

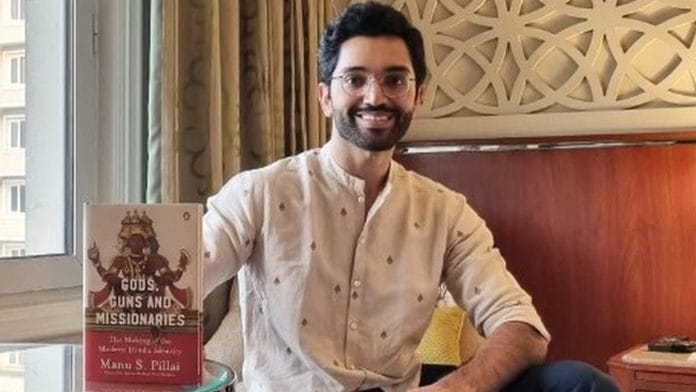

While conversions did happen, the story isn’t so simple, as author and historian Manu Pillai argues in his new book, Gods, Guns, and Missionaries: The Making of the Modern Hindu. He writes about the valiant Hindu pushback against the British Raj’s Christian conversion project. And it is in this response that Pillai locates the roots of modern Hindu identity and Hindutva.

“The story really begins with the encounter between European power and Hindu society. It’s about politically backed Christianity,” said Manu Pillai in an interview with ThePrint. “It’s that tension between foreign power and local religious systems and culture.”

The book explores this civilisational interface and how it led to creative reinterpretations of Christianity and Hinduism. Pillai describes it as “a multi-layered effort to understand what happened over those last 400 to 500 years that leads up ultimately to the birth of Hindutva”.

Here are edited excerpts from the conversation. For the full interview, do visit ThePrint’s YouTube channel.

RL: Right now, the Hindu victimhood narrative is dominant, and the last few hundred years are being portrayed as a period of repeated assaults on the Hindu faith. And yet, when I read your book, it’s mostly about Hindu resilience and how the Hindus fought back.

MP: There was an entire generation of British colonisers in India who were very pro-Hindu culture. They were smashing coconuts at temples, giving donations to Tirupati and the Padmanabhaswamy Temple, participating in Hindu rites, commissioning astrologers to decide things for them… at that stage of colonialism, they wanted to fit in with Hindu society.

But then, there were events happening in Britain also. There was the rise of evangelicalism there. A new form of Christianity emerged in this period. And when that happened, it became about evangelical attacks on Hinduism, to which Hindus were also responding. Even in colonised societies, there is no such thing as abject surrender.

By the 19th century, with British power entrenched and controlling so much of India, [conversion] became more and more of a threat. That’s when this great appetite grew to somehow define the contours of Hinduism and be able to push back and say, no, this is not going to work

It’s not really a story of some kind of siege of Hinduism, or some kind of war on it. The British didn’t have that kind of total power either. Yet, it was influential, it did cause a kind of soul searching in Hindu society. It did result in calls for reform, and a new framing of what it means to be Hindu and what Hinduism itself is.

Also Read: Mughal historian Swapna Liddle is Lutyens’ Delhi’s new toast. She isn’t caught in history wars

RL: So, you’re looking at the colonial period beyond just commerce and power—you’re looking at conversion as one of its central motives. And you’ve quoted Dalhousie as saying religious conversion to Christianity actually gives colonialism a taller purpose.

MP: When the first missionaries came to India, they saw a very alien culture—something they didn’t recognise at all. They were convinced that all Hindu gods are monsters, that these are all representations of Satan sitting in Hindu temples.

Then, with a little more exposure, they started saying, okay, hold on. Clearly, there’s a theology to this. Clearly, this culture has its own rationale and logic. We need to study this. Conversion is still the goal. But there was a willingness to try and appreciate what the local culture was about.

Then, you had the Protestant Reformation happening in Europe. By the 18th century, there was a whole set of intellectuals in Europe saying that the church had got it wrong—let’s go and see what the Hindus have in their philosophy that will help us support our project of reason and rationality and a new conceptualisation of God.

RL: There is the binary that many of these people created between what you call the lesser Hinduism and the higher Hinduism—the philosophical bedrock of the faith and the everyday ritualistic Hinduism.

MP: Remember, Europe had this narrative, especially after the Protestant Reformation, that religion and scripture got corrupted under the Catholic Church. And that’s why you needed the Reformation. And they applied that lens to India as well, which is that there is pristine Hinduism… It’s about the abstract divinity. It’s about, you know, God in his highest sort of conceptualisation. It’s about ideas.

There were rumours that the East India Company would send a whole platoon of missionaries to convert everybody… That’s when regimentation [among Hindus] became more of a real thing. It paved the way to Hindutva, that hardening of attitudes, the feeling that, okay, we need to now become defensive about faith

And then they actually came to India. They saw that we sing in temples, have rituals and goat sacrifices and so on. So, they started saying that, here also, there was a decline from some kind of pristine purity to some kind of a mess. And that’s why they started prioritising that older version—that pristine, pure version of Hinduism—over the living culture of the Hindus. That’s essentially the binary they created.

But Hinduism itself is a composite religion. It doesn’t come out of one source. It’s a conglomerate. A confederacy of sorts. It has one explanatory framework [but] others reject it. There are those who say, no, we do feel that the heart of Hinduism is in the rituals, is in the temples, is not merely an abstract philosophy, it is in living culture.

At the time of the enlightenment, people like Voltaire were very besotted with the ideas in the Vedas. None of them actually read the Vedas, but they were convinced that the Vedas somehow held monotheistic ideas that predated the Bible, that predated revealed religion. And they often used what they thought of as Hindu ideas in their fight against the church.

And that’s the big interesting thing about Hinduism, right? Because it’s such a diverse faith, it’s got such an archive of ideas, even in the scriptures. There’s just so much happening that different people could read different things into it.

RL: That leads us to the next question, which is about the multiplicity and plurality of the Hindu faith. There was no one book, no one god. This kind of staggering diversity within a faith almost makes it look disorganised, easier to occupy and convert. But your book suggests that this multiplicity helped us. So, how did it help us? And what do we derive from that for 21st-century India?

MP: [Missionaries] always come across this Hindu attitude that God has created multiple ways to find Him, and we accept that yours is one way, but it’s not our way. We have a different way. Whereas for missionaries, because they are in a foreign country to propagate their faith, they say, no, this isn’t a buffet where you can go and pick what you want. God is one, which means that God could only have revealed one way.

There were rumours that the East India Company would send a whole platoon of missionaries to convert everybody. There was this great suspicion, once we came under British rule, that there was always an effort to convert people to Christianity.

What is the text of the Hindus? Is it the Vedas? Is the Gita? These debates emerged. And the Gita became very popular as a sort of handbook of Hinduism. It’s a traditional text. We inherited it, but it’s also something that Europe appreciates, which means we could use it against missionary pressures and say, no, these are our ideas.

That’s when regimentation [among Hindus] became more of a real thing. It paved the way to Hindutva, that hardening of attitudes, the feeling that, okay, we need to now become defensive about faith—it became a way to justify resistance to Christian missionaries and evangelical motives.

By the 19th century, with British power entrenched and controlling so much of India, [conversion] became more and more of a threat. That’s when this great appetite grew to somehow define the contours of Hinduism and be able to push back and say, no, this is not going to work.

RL: And was that tweaking done with Europe in mind or the European gains in mind? And can you tell me about what kind of changes or distortions that brought to the faith?

MP: By the 19th century, Indian intellectuals were also looking at European ideas. It’s a two-way street. Just as the Indian ideas were going into Europe—where European intellectuals were mining Hinduism for their battles and their intellectual debates—Hindu minds here were also actively consuming a European framework.

So, Ram Mohan Roy, and figures like him, almost implicitly recognised that religion, as it’s defined in its dominant framework by the West, features books, a philosophical set of ideas, a certain kind of dogma. And they were trying to see how Hinduism can be made to fit that mould.

And what Hindus have is a religious system that has a very different evolution. It’s a living, breathing organism. It has no fixed contours. It’s a diverse tradition… [so] there was an attempt towards a unified way to understanding it.

Under colonial pressures and exposed to modern education, English ideas, the English language etc, a lot of reformers in India started trying to put Hinduism in this modern mould, and that’s where they started prioritising texts.

What is the text of the Hindus? Is it the Vedas? Is the Gita? These debates emerged. And the Gita became very popular as a sort of handbook of Hinduism.

It’s a traditional text. We inherited it, but it’s also something that Europe appreciates, which means we could use it against missionary pressures and say, no, these are our ideas.

You’ve brought in that [European] gaze, but you’re using it for your own purposes to push back.

RL: Is it safe for you to be a public historian today talking about conversion?

MP: Well, it’s an anxious and fraught time in general to talk about history because history is very politicised, right? History is not just the past. It is very present. We are still renaming cities. We are still fighting over who did what, at what period of time.

And it’s understandable. Societies draw meaning in the present by interpreting and sometimes reinterpreting the past. That’s just the nature of the world. That’s where the historian really comes in to clarify and nuance things.

Political parties have ideologies. Ideologies are supported by interpretations of history.

Is it safe? Well, my very first book got me a defamation notice with many crores written on it. I’ve been cancelled at different points by the right, by the left. But it doesn’t matter.

I think there are enough intelligent, sensible people around who are actually interested in these topics, and that makes it worth it. And yet, we’ve had a late emergence of public historians in India. William Dalrymple recently said that it’s because of our Indian academics’ failure that many Indians are moving to what’s called WhatsApp history today. I think it’s possible that we may have flattened it a little bit, but I understand what he was trying to say. To the extent that we have really good research that is done in academic spaces, but it is not necessarily communicated outside of those spaces.

At the same time, we have a huge bubbling up of interest in history. History is political, people are interested in the past. And somehow, this part of the conversation is monopolised largely by populist history. There’s a difference between popular history and populist history.

Also Read: Doniger, Truschke, Pollock didn’t ‘kill’ Sanskrit. Brahmins did

RL: Have you read Discovery of India by Jawaharlal Nehru? Would you say that he was performing the role of a public historian?

MP: That’s an interesting question. He was certainly channelling history to give the present a certain meaning and emphasis and interpretation. I don’t think he saw himself as a historian engaging with history as such. For him, it was more about drawing meaning in the present and trying to understand what kind of India existed. Nation-building was part of that.

So, I think he was more of a political thinker who was marshalling history for a political project. Everybody does it. Political parties have ideologies. Ideologies are supported by interpretations of history.