New Delhi: Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay’s tryst with the millennia-old Indus script started over a dinner conversation with a Cambridge University professor in 2014. Since then, the 42-year-old software engineer hasn’t looked back.

“I have been fascinated with this script since 2010 and sought scientific analysis to understand it,” said Mukhopadhyay, recalling how she approached Ronojoy Adhikari, a Cambridge professor who had worked on the script earlier, for research assistance.

While the duo parted ways in just three months, Mukhopadhyay’s obsession with the Indus script only grew. She continued her research, challenging established theories and focusing on the script’s structural nature and mercantile origins.

Over the last 100 years, experts from across the spectrum – archaeologists, linguists, epigraphists, engineers, civil servants, cryptographers, historians, and scientists – have made several failed attempts to understand the Indus script. While research approaches have gone from traditional epigraphic methods to computational and statistical ones, the mystery has remained unsolved. But with Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin’s recent announcement to confer a million-dollar prize upon those who decode it, there is renewed vigour to decipher this corpus of Harappan symbols. A new wave of scholars is turning to AI and advanced methodologies to crack the code.

Bahata Mukhopadhyay and cryptographer Bharath Rao aka Yajnadevam, two independent researchers from vastly different fields, are at the forefront of deciphering this elusive script.

Mukhopadhyay was even part of the three-day Chennai seminar where Stalin declared prize money for Indus script researchers. “We have not been able to clearly understand the writing system of the once flourishing Indus Valley…The efforts of the state government are to ensure the right place for Tamil Nadu in the country’s history,” the CM had said.

He also laid the foundation for a statue of British archaeologist Sir John Marshall, credited with discovering the Indus Valley Civilisation in 1924. On top of this, Stalin allocated Rs 2 crore to establish a research chair in the name of Iravatham Mahadevan, a civil servant and eminent scholar of the Indus script from Tamil Nadu.

I have used a cryptogram approach to deciphering the Indus script. I wanted a hard problem to keep me occupied — Yajnadevam, cryptographer

Welcoming Stalin’s announcement, Mukhopadhyay said it would push many scholars to decode the script. “For a long time, there has been no such organised effort.”

In December 2024, in Rajya Sabha, Union minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat had addressed questions about ongoing efforts to decode the Indus script. “There is no such proposal to launch scientific study to investigate the population history of South Asia using genomics to address conflicting theories,” he had said in the context of deciphering the script.

A puzzle so far

In the absence of a Rosetta Stone-like artefact – which helped scholars decode Egyptian hieroglyphics – and a lack of bilingual texts, making sense of the Indus script remains a big challenge. Each symbol varies in form and style. And most inscriptions are remarkably short, ranging between two and 20 symbols.

Scholars such as the epigraphist Iravatham Mahadevan and Finnish Indologist Asko Parpola linked the script with Dravidian languages. Others, such as the computer scientist Subhash Kak, suggested that the Brahmi script had been derived from the Indus script.

Mahadevan’s work is more focused on the script’s internal structure and syntax and doesn’t commit to a specific linguistic context. Asko Parpola’s work, on the other hand, is more linguistically oriented, with a focus on deciphering the script’s meaning and its connection with the Dravidian language family. Both concluded, however, that the Indus script was linked to proto-Dravidian languages.

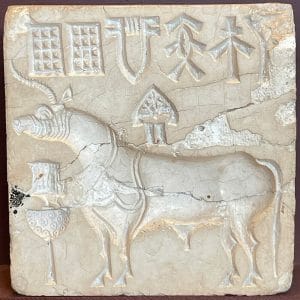

The Indus Valley Civilisation flourished in large parts of modern-day Northwestern India and Pakistan, over an area of about one million square kilometres. The Indus script symbols revealed during excavations were inscribed on terracotta tablets and seals.

But there was never any consensus on the number of symbols. Mahadevan listed 417 distinct signs in 1977, Parpola estimated 386 signs in 1994, and epigrapher Bryan Wells estimated 694 signs in 2015.

In the early 2000s, some researchers questioned if these symbols were a language at all.

In 2004, historian Steve Farmer, computer linguist Richard Sproat, and Indologist Michael Witzel in a paper claimed that the script did not constitute a language-based writing system.

In the last decade, however, independent researchers such as Mukhopadhyay have contended that each sign of the Indus script holds a specific meaning.

Omar Khan, founder of Harappa.com said earlier this month that AI could assist scholars in deciphering the script of the Indus Valley. However, it is crucial to not equate AI with magic, stressed Mukhopadhyay. “You must use the technology in the context of the subject domain.”

Also read: See how Gujarat’s Kanmer links to Dholavira, Harappa—India’s urbanisation journey lies here

New scholarship

Bahata Mukhopadhyay’s focus on the script’s structural and mercantile roots contrasts with Yajnadevam, who uses cryptographic methods to study it.

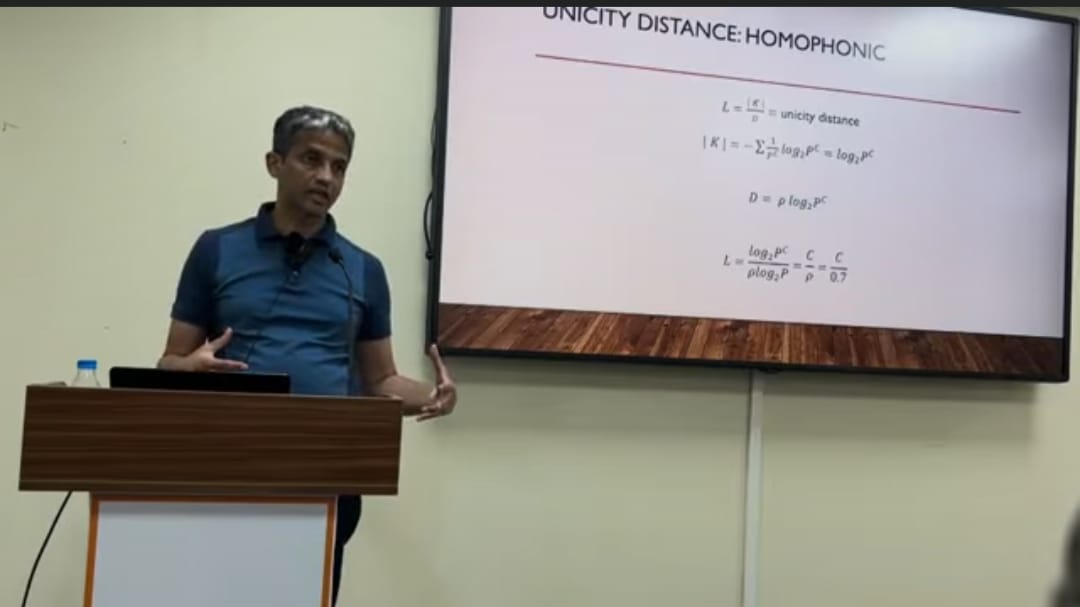

Yajnadevam claims his research approach is the only one that makes good use of decades-old methods and foundations of information theory.

“I have used a cryptogram approach to deciphering the Indus script. I wanted a hard problem to keep me occupied,” said Yajnadevam, a US-based cryptographer who started working on the script during Covid-19. “Cryptanalysis has been successfully used in deciphering many scripts,” he said, adding that the key to decoding the corpus is to digitise it “and create an inventory of signs”.

His research paper ‘A Cryptanalytic Decipherment of the Indus Script’, is not yet peer-reviewed and currently available on Academia.edu. However, it has still managed to spark conversation among scholars.

According to Yajnadevam, his work challenges old notions about the nature of the Indus civilisation, its antiquity, its supposed discontinuity, and the ingress of Sanskrit in the mid-2nd millennium.

In his paper, he treats the script like a large ‘cryptogram’, a concept introduced by American mathematician and computer scientist Claude Shannon. “We decipher every sign sequentially using regular expressions and set-intersection. Brahmi glyphs are discovered to be standardized Indus signs,” reads his paper.

Yajnadevam claims that Indus inscriptions are written in grammatically correct post-Vedic Sanskrit. Seventy-six ‘allographs’ (alternate forms of the same letter or character) constitute most signs in the script. Conjunct signs (combinations of two or more symbols), make up the rest.

“Our decipherment can read every inscription and we translate 500+ inscriptions including the 50+ longest, 50+ shortest and 400+ medium-sized inscriptions including 100+ inscriptions with conjunct signs,” he wrote.

Yajnadevam is eyeing Stalin’s million-dollar prize too. After the CM’s announcement, he wrote a post on X tagging Tamil Nadu’s finance and archaeology minister Thangam Thenarasu: “Please advise on how to claim the 1 million dollar announced by the TN government.”

Praising the state government’s announcement, he said: “It’s a wonderful initiative to resolve a longstanding problem.”

Bahata Mukhopadhyay, who also dabbles in poetry, self-schooled herself on the complex subject of the Indus script. She even resigned from her software company Infor and took a year off to explore the nitty-gritty of a script that was completely alien to her at the time.

“That time was very fruitful for me and I explored many books on this subject and learned how ancient scripts such as Linear B were deciphered,” she said.

In the last five years, Mukhopadhyay has published three research papers in the peer-reviewed journal Nature. Her first paper, published in 2019, focused on the structural aspects of the Indus script. Her second paper, published in 2021, spoke about the linguistic diversity in the Indus Valley Civilisation. And her third one, published in 2023, indicated that the Indus script encoded rules and information about ancient taxation and commercial licensing.

Her initial findings suggest that the structures on the seals are not phonetic and are largely logographic – which means that individual symbols represent things. “Most scholars have not analysed the script this way. I studied the signs individually and established the structure,” said Mukhopadhyay.

Also read: Daimabad was home to skilled agriculturalists—even before Harappans’ cultural influence

Dravidian roots

Over the decades, there has been a concerted effort to connect the Indus script to Dravidian languages.

At the event where Stalin announced his million-dollar prize, he also released a book titled Indus Signs and Graffiti Marks of Tamil Nadu: A Morphological Study. Authored by Professor K Rajan, academic and research advisor to the state’s archaeology department, and R Sivanantham, the department’s joint director. According to a report by the same authors, more than 90 per cent of the ancient graffiti marks found at 140 archaeological sites in Tamil Nadu have parallels or similarities with Indus Valley Civilisation symbols.

I explored many books on this subject and learned how ancient scripts such as Linear B were deciphered – Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay, software engineer

In her 2021 research paper, Mukhopadhyay wrote that the Indus Valley Civilisation script was rooted in ancestral Dravidian languages.

Mukhopadhyay also told ThePrint that some Indus signs, which might have used Dravidian symbolism, can be linked to Proto-Dravidian root words. Giving an example, she said some fish signs of the Indus script likely formed mina, the Dravidian word for fish. She further explained how the words used for elephants in Bronze Age Mesopotamia – such as pīri, pīru – were borrowed from pīlu, a Proto-Dravidian elephant-word that was prevalent in the Indus Valley Civilisation.

In her paper, she wrote that ‘pīlu’-based words, used to convey the meanings of ivory, elephant and toothbrush in IVC, originated from the Proto-Dravidian tooth-word pal/pīl.

Also read: Tamil Nadu has the largest Iron-Age urn burial site. We must look beyond our Harappa frenzy

The mercantile script

According to Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay, decoding Indus signs will help reconstruct the ancient economy. It was, after all, a mercantile script used mainly for commercial purposes.

Mukhopadhyay has argued in her research that Indus seals are like revenue stamps, possibly recording taxed commodities, licensed crafts, and tax rates.

Archaeological evidence suggests, said Mukhopadhyay, that these seals were also used for commercial purposes. This is because the script is found mainly on seals and not on other mediums.

“Indus people were trade savvy and it was a complex economy. The inscribed stamp seals were primarily used for enforcing certain rules involving taxation, trade control, commodity control and access control,” she said. Indus seals found near city gates (such as in Harappa) and craft workshops (such as in Chanhu-daro) were often used for taxation along with standardised Indus weights, she added.

According to Mukhopadhyay, there is a possibility that Harappan people had other regional scripts. They could have been lost as they were mainly written on perishable materials.

“When the administrative structure of the Indus Civilisation collapsed, administrative tools like writing also disappeared,” she said.

The Indus script did not phonetically spell out words, she added. It had no alphabets or syllables and used symbols to explain different words and meanings.

“Each Indus script sign has a rich and complex story to tell us,” she said.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

Here is a recent result which actually cracks the Indus Valley Script. This was done using cryptanalysis and it solves it completely and shows that it is mathematically also correct using shannon’s criteria.

https://www.academia.edu/78867798/A_cryptanalytic_decipherment_of_the_Indus_Script&ved=2ahUKEwj5ru389oGLAxX22TgGHQFGIsQQFnoECC0QAQ&usg=AOvVaw1b1QEKiteqUl4cBBVIImBe

The paper is still being updated to make it more accessible to people. But the current version has all that is needed to verify correctness.