New Delhi: Thousands of faces are frozen in time at Mumbai’s Hamilton Studios—from maharajas and magnates to would-be migrants posing for passport photos. Now, owner Ajita Madhavji is racing to save the 96-year-old photography studio’s historic collection, teaming up with archivists from Coventry University, UK, to digitise two decades of post-Partition photographs before they’re lost forever.

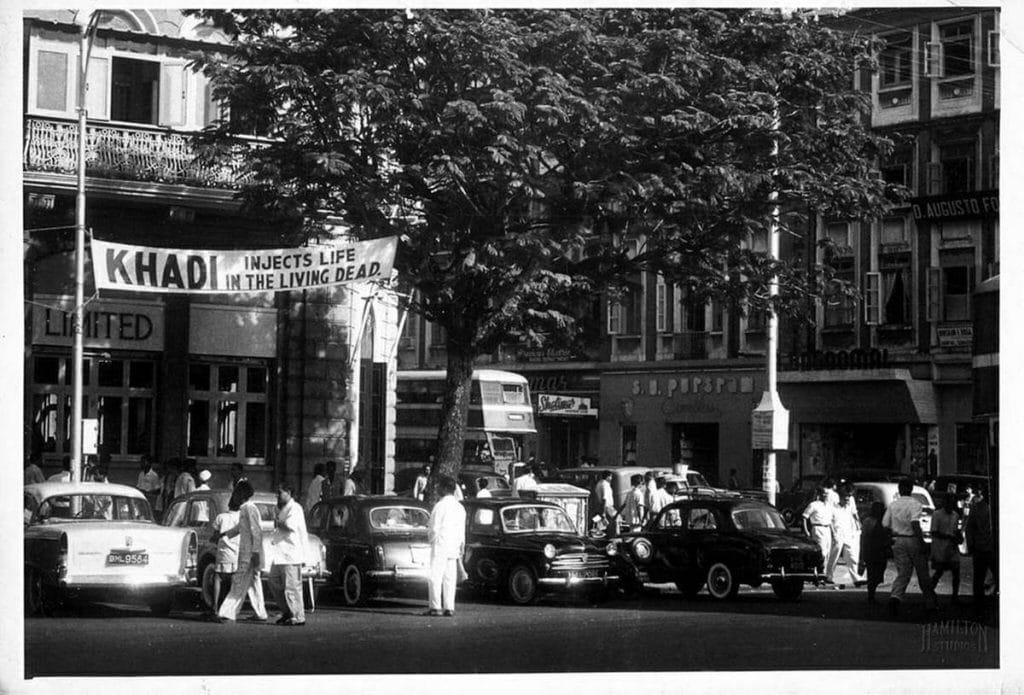

This phase of the Hamilton Studios project will digitise over 20,000 artefacts—negatives, prints, and documents—from 1947 to 1967, a period of political upheaval in India as well as mass migration to the UK. These images and documents offer a window into a country in flux—as well as the people and moments shaped by that upheaval. It’s a reliable contribution to collective memory amid contested histories of Partition.

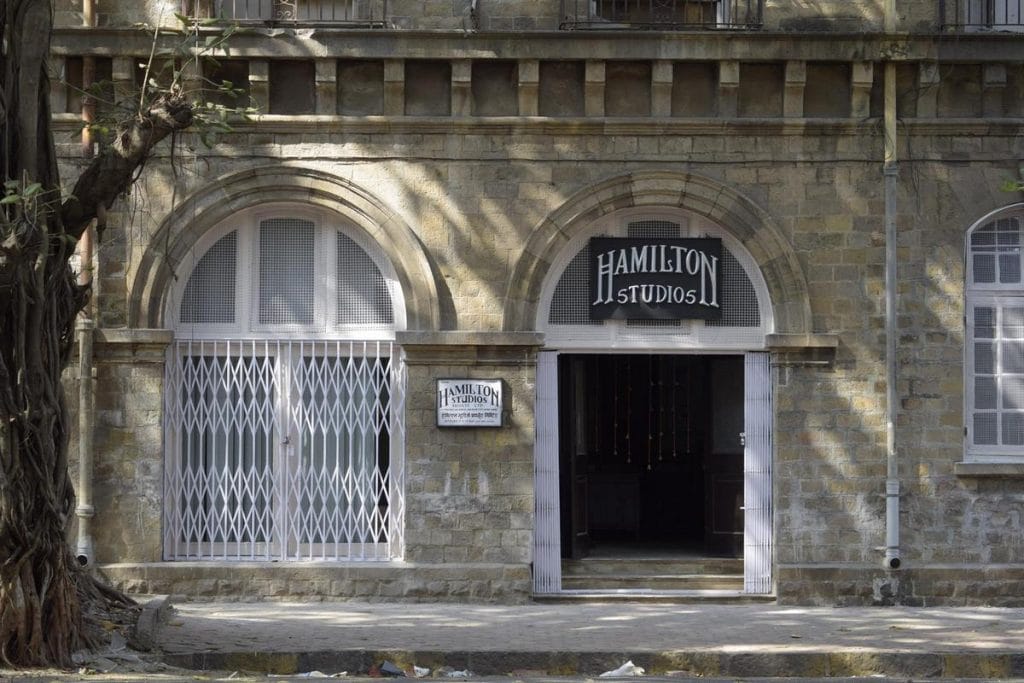

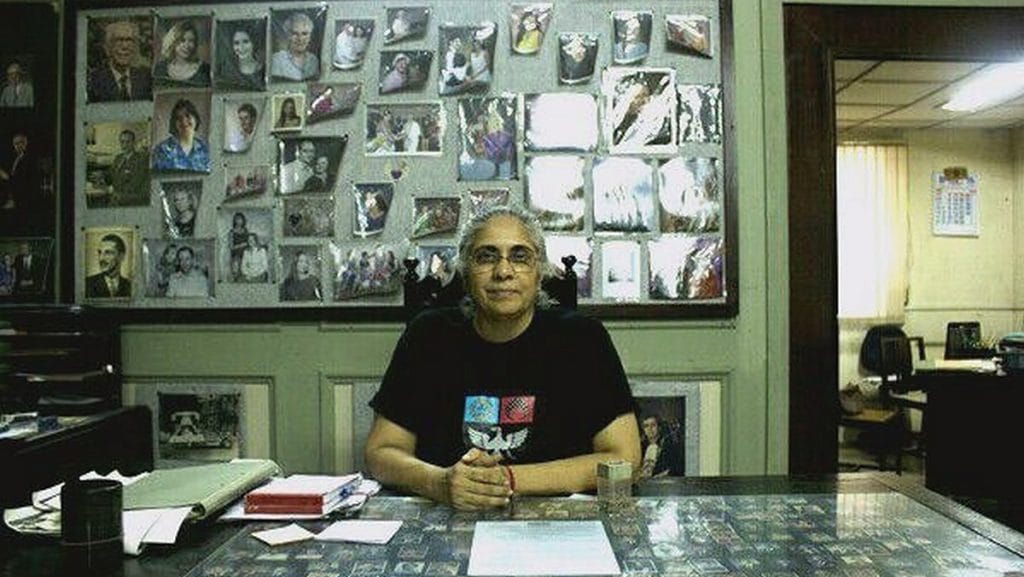

But for 68-year-old Madhavji, this isn’t just about history—it’s also personal. She’s fighting to protect the legacy of her father Ranjit Madhavji. He bought the studio in 1958 from Italian businessman Sir Victor Sassoon, but Hamilton’s history goes back to 1928, making it one of India’s oldest surviving photo studios. With 600,000 images and documents spanning nearly a century, the studio in Mumbai’s Ballard Estate is a treasure trove of history. But it’s just about hanging on, with court cases over the building and a waning business.

With so much to handle, preserving the archives took a back seat—until an opportunity came along in 2017 to collaborate with professional archivists. Madhavji jumped at it.

“We were delayed as far as the archiving process was concerned,” Madhavji told ThePrint. “But I always wanted the Hamilton collection to become something like an educative institution where people—especially students —could learn from it.”

The post-Partition archiving is the second phase of the Hamilton Studios digitisation project, building on an earlier effort that digitised pre-Independence photos. The present exercise is taking place at the Mumbai studio, overseen by digital archiving expert Ben Kyneswood of Coventry University, and is set for completion by October 2025. The project is supported by the Modern Endangered Archives Programme at UCLA Library and funded by Arcadia, a foundation dedicated to cultural preservation and open access Interns from the National Institute of Design (NID) are also assisting with the archiving—just as they did in the first phase.

“There’s so much to learn from an old photograph,” Madhavji added. “This was always my idea for Hamilton. I never wanted the archives to just be used commercially.”

Also Read: British photographers showed sites of 1857 violence, without people. They erased Indians

New chapter for Hamilton archives

A chance encounter at the 2017 Kala Ghoda Arts Festival changed everything for Ajita Madhavji.

After years of turning down business offers to monetise Hamilton Studios’ archives, she met a photography enthusiast who suggested a different path—partnering with the British Library. That’s how she got connected with Dr Benjamin Kyneswood, associate professor in Digital Heritage and Culture at Coventry University.

“Ben said he could help collaborate between the British Library and us, and that he’d be the in-between party,” Madhavji said. “That’s how the whole thing started. The ball started rolling, and we made an application.”

The collection includes passport photos, glass and celluloid negatives, test prints, and invoices that reveal the photography techniques and business practices of the time. Advertisements from the era give a snapshot of the consumer culture of the time.

The first batch of digitised material will cover 1947 to 1951, focusing on Indians who migrated to the UK under the 1948 British Nationality Act. The second batch, from 1963 to 1967, captures a surge in migration—by the 1971 UK census, the British-Indian population had grown tenfold since Partition. The third batch from 1951-1963 will be looked into after completion of the other two batches.

“The period from 1947 to 1967 is truly fascinating, filled with upheaval after Partition,” Kyneswood told ThePrint. “We found many passport photographs from that era, as families sought new lives in the UK, Kenya, and beyond. These photos captured young people—18 to 20-year-olds—on the brink of change.”

Faces in the crowd

Hamilton once boasted of an impressive clientele—from lords and ladies during British rule to Dr BR Ambedkar, industrialist JRD Tata, and Bollywood stars like Vinod Khanna and Zeenat Aman. The studio’s early portraits were known for their distinctive luminosity, with sharp details. Such is the fame that in 2015, a descendent of Russia’s Romanov dynasty especially came to get a portrait made in the studio.

Since taking over the studio in the 1980s, Ajita Madhavji has expanded its services to include bespoke exhibitions. Yet maintaining the archive of historic portraits, street scenes, and royal weddings has been a constant challenge.

One major issue is Mumbai’s humidity. With the studio’s 20-foot ceilings, multiple humidifiers are needed, driving up costs. The heat also puts the celluloid materials at risk of melting and the air conditioning has to run 24/7—adding to the massive electricity bills. Without institutional support, the financial strain has been overwhelming.

And then there’s the rise of phone cameras and editing apps.

“Photography today isn’t specialised and everyone is a photographer nowadays, with an iPhone in their hands. Who needs studios anymore?” said Madhavji wistfully.

But now, they have become more relevant than ever—not just the glamorous shots of movie stars and royalty, but ordinary portraits too.

“Connecting everyday people to their history is really important. These individuals, who rise each morning, work hard, and care for their families, may not be famous, but they deserve this spotlight,” Kyneswood said. “We may even find living relatives or their children who still have prints at home. But the original negatives, with their greater detail, offer so much more potential.”

Also Read: How John Edward Sache photographed 19th-century India

Countering ‘political narratives’

The work to preserve Hamilton’s archives is part of a broader movement to save the memories of Partition and the years that followed. The project complements academic initiatives like Stanford’s and Harvard’s respective 1947 Partition Archives, as well as private collections such as the Indian Memory Project and the Delhi-based Partition Archive.

But in India, securing resources for cultural preservation is an uphill battle, and according to Anusha Yadav, founder of the Indian Memory Project, it’s often brushed off as a “first world problem”.

“We are currently riding a zeitgeist but we can’t rely solely on entrepreneurship. It is brave for Ajitaji to have that grit because there is a lot of law and politics behind grants,” said Yadav. “It is a privilege since India is not able to offer cultural personnel yet and documenting physical archives is a task. Culture is power but you need resources to empower.”

In the wake of Partition, entire generations struggled with trauma and displacement. It took decades for communities to openly confront the pain. Photographs became one of the few tangible records of that time, offering a more nuanced understanding of the past—and challenging the often jingoistic narratives surrounding Partition.

These visual chronicles resonate not only in India, but across the border in Pakistan.

“These photos give us a more detailed view of the past, beyond the usual political narratives,” said Anam Zakaria, a Partition historian from Pakistan. “The preservation of the tangible and intangible memories of Partition and post-Partition years is so critical, especially at a time when we are at the brink of losing this history.”

Yadav compared the preservation of memories to piecing together clues in a detective novel. Without them, she warned, future generations would struggle to understand their identity.

“In 20 years, without family stories and visual memories, how will we locate our identities?” she asked. “And if you forget collective identities, you cannot have a future or a national memory. When we fail to preserve our history, narratives can be misappropriated.”

For Ajita Madhavji, Hamilton Studios may be struggling to keep its footing in a fast-paced digital landscape, but it’s standing firm as a guardian of history and an encyclopaedia of a bygone era.

“It’s a legacy entrusted to me, and I won’t trade it away. It needs to be preserved and treasured, and it’s something that can be passed onto future generations,” she said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)