Sonipat: A handwritten screenplay of Girish Karnad’s Samskara, Sai Paranjpye’s scribbled notes for Chashme Baddoor, and the personal papers of former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh have found a new home. Ashoka University’s Archives of Contemporary India is redefining what such a repository can be—not dusty and fusty but modern, cutting-edge, and alive with history.

The first private archive of its kind in India, it’s slowly becoming a favourite destination for eminent personalities looking to preserve their legacies, especially after visiting the facilities.

“The first response of most people, after we reach out to them, is usually to come and see—they want to know whom they are handing over their precious works to,” said Deepa Bhatnagar, director of the archives. “We also do not immediately push for acquiring the works. It’s a gradual process of building trust.”

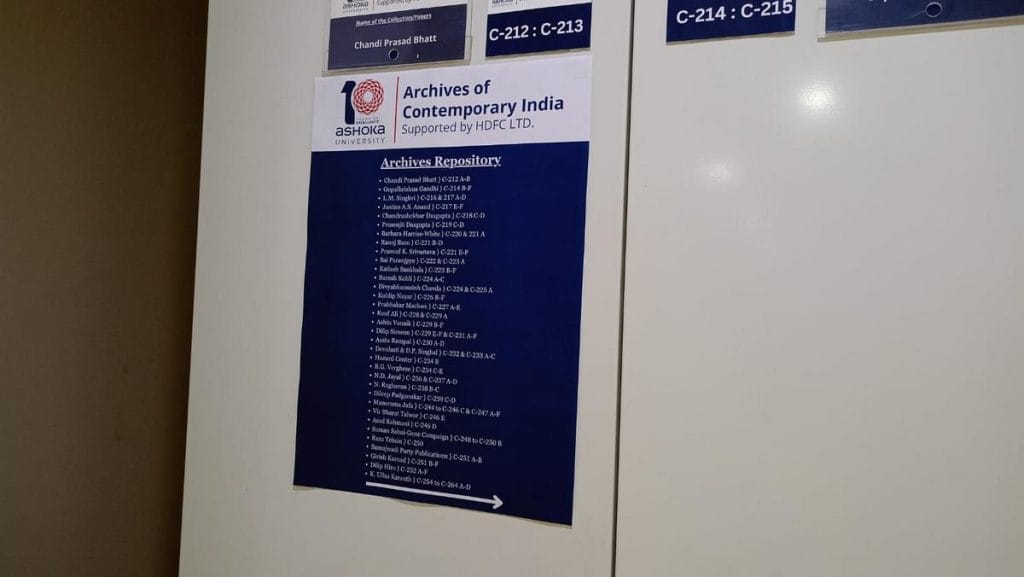

Spread over 1,500 square metres in Ashoka University’s Sonipat campus, the archive challenges the stereotype of decaying, forgotten records crammed into old cabinets. It’s housed in a temperature- and moisture-controlled hall designed to preserve fragile materials and make them accessible. In just two years the archive has catalogued a diverse and extensive collection—including the papers of India’s second President Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, historian Narayani Gupta, Chipko Movement pioneer Chandi Prasad Bhatt, novelist Kiran Nagarkar, and filmmakers and playwrights such as Karnad and Paranjpye. It even hosts The Hoot’s digital archive.

Private archives are not a new concept in India. Across fields, such collections are slowly being established to fill the gaps left by the crumbling structures and poor infrastructure of national and state archives. But Ashoka’s archive is the first within a private university, using the latest technology from the start. While public archives are inching toward digitisation, Ashoka’s team catalogues and digitises simultaneously.

The archive’s journey began in 2017 when then vice-chancellor Rudrangshu Mukherjee, a historian and author, championed the idea of creating Ashoka’s own repository. He brought in Bhatnagar, a seasoned archivist, to make it happen.

At first, the project moved slowly, with the archive starting out as a spare room in the administrative building. Most people in the section had no idea what archives were, but made space for Bhatnagar and her team of just one other person to figure out the basics—how to store fragile materials, connect with potential donors, hire staff, and build a functioning operation from scratch.

Finally, two years ago, that cramped room was swapped for a sprawling, purpose-built basement. Now, visitors step out of the lift to the archive’s striking red logo and enter cool, white-walled hallways where archivists are busy sorting and cataloguing. Rows of boxes, stamped with Ashoka’s logo, line the shelves in the records room.

Students have been putting the archive to good use.

“There are so many personal documents—from letters and interviews to unpublished works of prominent people. They’re a lens into someone’s mind,” said Arushi Bhargava, a Young India Fellow. “Where else will I see their creative process or original scripts, right in the university?”

Also Read: Hamilton Studios is racing to save Mumbai’s post-Partition faces. UK archivists are helping

‘I am the lucky one’

Nearly a year after filmmaker Sai Paranjpye donated her works to the Ashoka University archives, she flew down to Delhi and visited in person to see if Bhatnagar and her team were preserving them as well as they had promised. After an extensive tour on 17 October, the 86-year-old was satisfied.

“People think Ashoka is lucky to have my papers, but I am the fortunate one that my works will be preserved by the latest expertise and in such a wonderful space,” said Paranjpye.

The visit capped a process that began in 2022, when Ashoka’s archive team first reached out to Paranjpye. Archive associates Shivani Bajpai and Chirag Sharma also visited her home, carefully going through her collection and earning her trust.

Scripts and drafts of award-winning films like Sparsh (1980), Katha (1983), Disha (1992), Papeeha (1993), and Saaz (1997) are part of the collection, stored in brown boxes, neatly labelled and stacked. It also includes personal correspondence, photographs, and newspaper clippings.

Paranjpye’s visit included an interactive session with students and screenings of her films, including the Filmfare-winning Disha. For many, the hard-hitting drama about immigrant workers was eye-opening.

“After the screening of Disha, there was complete silence. Not one person clapped, and I was concerned. Then a young student said that he was actually too stunned to even react,” said Paranjpye.

The intensity of Disha surprised students who had previously watched her delightful comedy Chashme Baddoor.

“Disha was unlike anything I’ve ever seen,” said student Arushi Bhargava. “I loved how Paranjpye showed the village space and life. I am an architect and I kept drawing scenes from the movie during the screening.”

Paranjpye’s archive also offers insights into how her works have endured.

“When looking through her collection, what stood out for me is that her movies, especially Chashme Baddoor, have been watched and written about nearly every year,” said Mumtaz Mohiuddin, a scholar at the university. “It is testament to how relevant her films have remained.”

In her interactive session, Paranjpye charmed students with stories about her unusual childhood and flair for storytelling.

“I would spend a lot of time alone on my rocking chair,” she said, laughing. “My mother’s friend once asked if little Sai was quite alright.”

Paranjpye, who wrote her first book when she was barely 10, donated copies of many of her plays too, including Jaswandi and Sakhe Shejari, as well as works for children like Nana Phadnavis and Jaducha Shankh.

“She is extremely witty, and did not try to flaunt anything. I liked the fact that she also acknowledged her privilege of being born into the kind of distinguished family she had, and how her mother’s encouragement was crucial,” said Mohiuddin.

Building an archive

When Rudrangshu Mukherjee, former VC of Ashoka University, decided the university needed its own archive, the idea was ambitious but abstract— even after archivist Deepa Bhatnagar was roped in.

Bhatnagar recounted Mukherjee pointing to an under-construction building and saying, “That’s where the archive will be”

For years, she worked out of a temporary set-up in the administration block, waiting for the space to be ready. Covid delays didn’t help, but by the time the new facility was completed in 2022, the archive was finally ready to start its mission in earnest.

The team began collecting materials well before the space was ready — but key archiving processes like fumigation, digitisation, and staffing could only start once the facility was complete, with scanners and preservation chambers in place.

“Almost everyone wants us to first meet them and see the kind of materials they have,” said Bhatnagar, who was previously a history professor at Jesus and Mary College and head of research and publications at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library.

She and her team have travelled across India—from Chamoli to Jaipur, Bengaluru to Mumbai—to convince people to part with their collections and personally take custody of documents.

What started off as a one-woman operation has now become a 12-member team, including six archivists.

Preservation with precision

Once a collection reaches the archive, the multi-step preservation process unfolds with scientific precision.

First, the papers are fumigated in massive chambers that look like sophisticated tandoors, glowing red when switched on. These chambers disinfect the documents, eliminating pests or insects that might eat away at the paper.

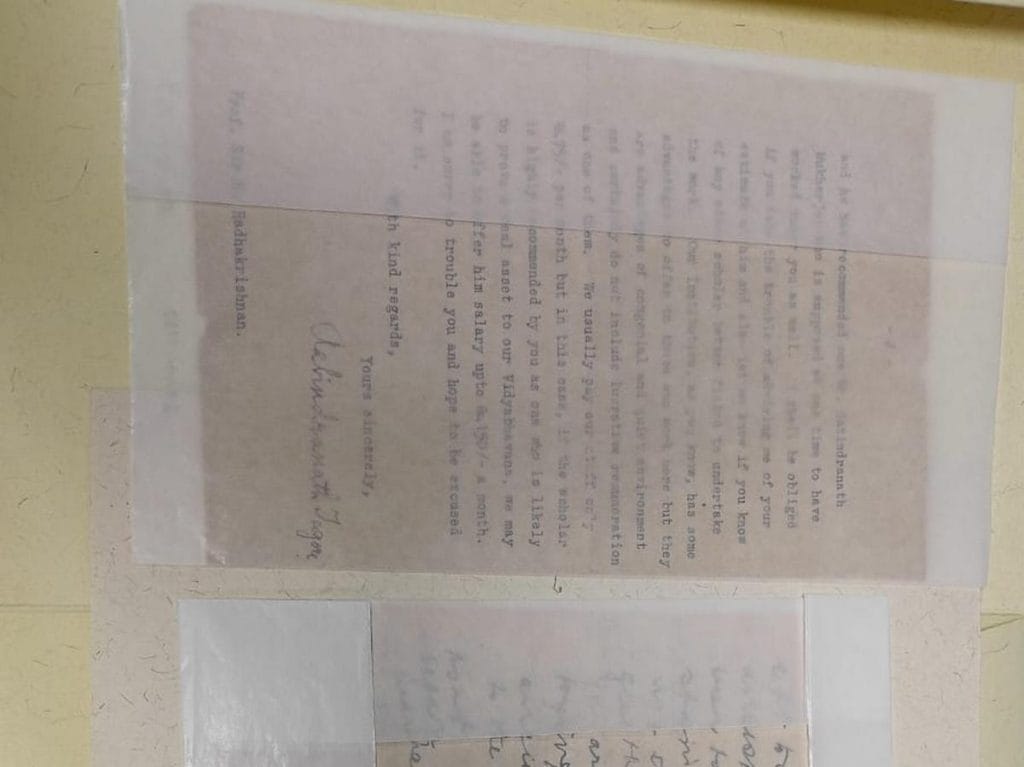

Aged and delicate papers are also layered with imported glassine sheets from the US to halt further deterioration.

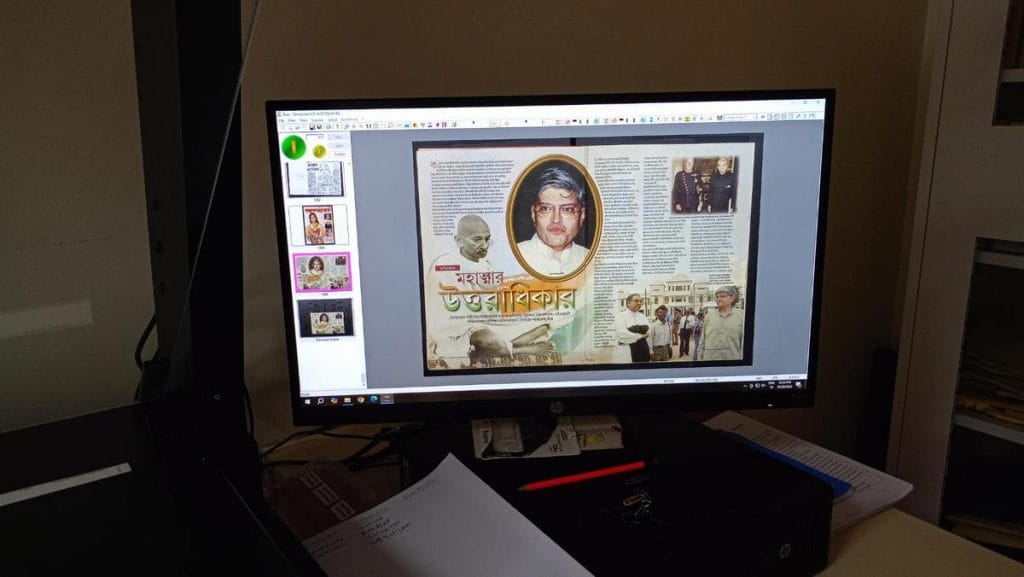

Next comes digitisation. Using a giant scanner, archivists create high-resolution images of each document. These images are later catalogued and uploaded online, allowing researchers from anywhere to explore the materials. In addition, students are educated about the process and importance of archives through various programmes and classes.

The facility has 24/7 temperature control to protect fragile materials.

“I have worked as an archivist in various government places, where the AC is turned off at 5 pm— I’ve seen the damage it does to documents,” said Bhatnagar.

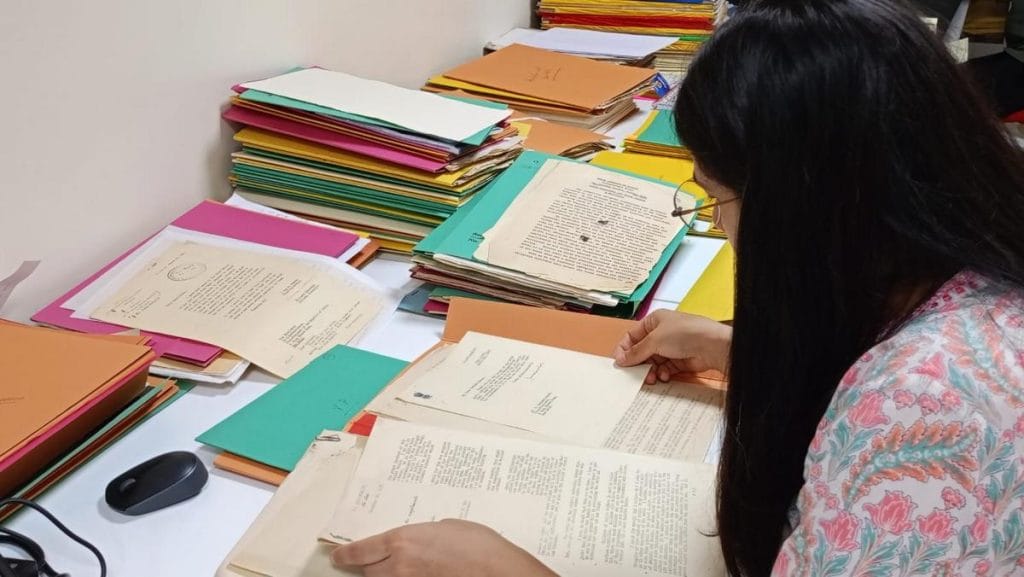

For the archivists, the day begins at 10 am and involves painstakingly cataloguing the collection they are assigned. A single person’s collection can take weeks or even months to organise.

“On the busier days, we also have talks or visits from eminent personalities or even student tours, and we are involved in interactions,” said Sonali Verma, an archives project associate.

For many, this is their first experience as archivists, and they’ve picked up skills on the job. Others, like Chirag Sharma, came with solid experience.

“I’ve worked at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library for almost eight years,” Sharma said. “I can safely say that the archives here have state-of-the-art infrastructure and skilled people handling all the material.”

The archive has made an impression on many visitors. Historian Narayani Gupta, after seeing the thorough processes, expressed regret that her husband’s papers were not preserved here, according to Bhatnagar.

“Professor Narayani Gupta said she wished we could have also preserved the works of her husband, the noted historian Partha Sarathi Gupta, which were donated somewhere else,” Bhatnagar said.

Also Read: Wars to Green Revolution to Emergency, National Archives are full of gaping holes

Stories that matter

Girish Karnad agreed to donate his papers to the Ashoka University archives just in time. It was 2018, just a year before his death, and the documents were in need of care.

“When we went to get the papers, he was about to shift houses. These were in boxes on shelves in a room adjacent to his office. I could see the dampness and moulding,” said Bhatnagar.

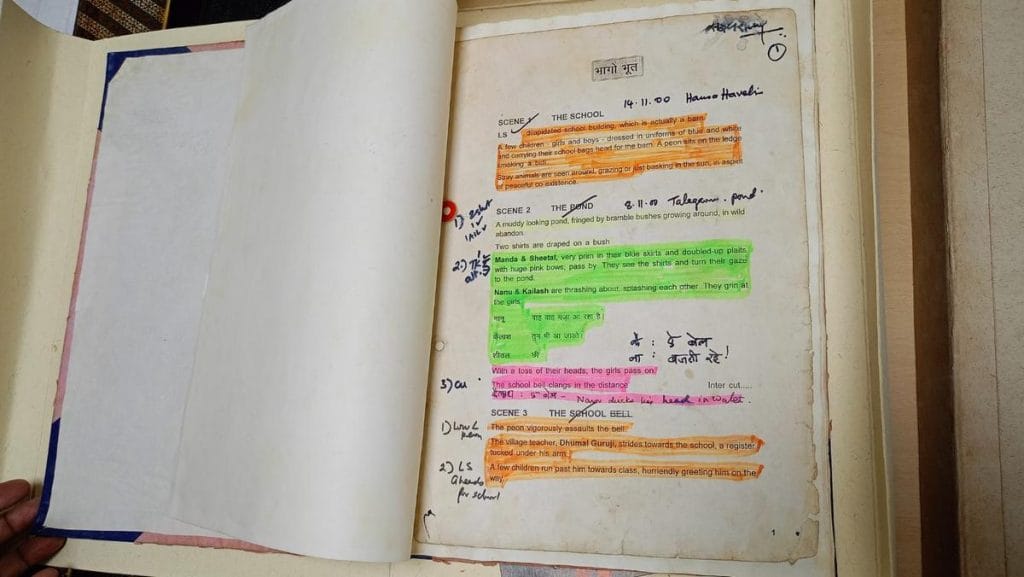

The materials include a photocopy of the script for Karnad’s iconic movie Samskara, handwritten drafts of Kanooru Heggadithi and Anveshana, and typed copies of his plays such as Nagamandala, Bali, and Rakshasa Tangadi. Filled with notes, cancellations, and improvisations, the papers offer a rare glimpse into how he brought his screenplays to life.

The collection is already proving valuable for researchers like Mohiuddin, who is using Karnad’s works for her ELM (Elective Learning Module) project.

“I am using his works in the archives to carve out the history of Karnad’s contribution to primarily Hindi cinema through his works in both Kannada as well as Parsi theatre,” she said.

Many other collections are also drawing scholars to Ashoka’s archive.

Retired IIM-Kolkata professor Jayanta Bandyopadhyay, now a distinguished fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, took a trip down to study documents related to environmental activist Chandi Prasad Bhatt.

“We have managed to find documents crucial to our research,” Bandyopadhyay said. “It is very impressive, the way they have built this up. You can have the best technology and money, but something like this also needs good human leadership, which the place got.”

Bhatnagar and her team, meanwhile, are busy growing the collection. Next on their list is the work of Aruna Vasudev, a film scholar, critic, and festival curator often called the ‘Mother of Asian Cinema’. Vasudev was the founding editor of Cinemaya, a film quarterly dedicated to Asian cinema that began publishing in 1988 and the recipient of the first Satyajit Ray Memorial Award

“She passed away a few weeks ago, and we are now in talks with her daughter to include her work in our collection, along with editions of the magazines,” said Bhatnagar.

But students have their own wish lists for the archives, with some eager to see a broader range of names.

“The archives are definitely helpful in knowing more about the key figures of contemporary India. But I want more subaltern history and people from the marginalised communities included too,” said Mohiuddin.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)