It was 1946 and Partition was all but a certainty. While Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s All India Muslim League pushed for the creation of Pakistan, it failed to create organisational networks early on to ease the lives of the people ‘belonging’ to what is today called Pakistan. Of these absent organisational networks was a newspaper aimed at serving as the people’s voice. It was not until May 1946 that Progressive Papers Limited was established and with it, Pakistan Times.

The paper, while not an official mouthpiece of the Muslim League, announced “We are a Muslim League paper” in its editorial by its first editor-in-chief, Faiz Ahmad Faiz.

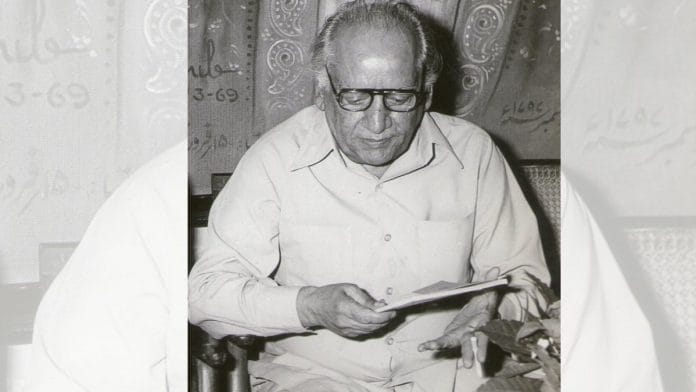

Faiz today is widely known as poet, author, communist, teacher and army officer. But editor-in-chief of Pakistan Times is an identity of his that is often overshadowed. His poem, Hum Dekhenge, has taken India by storm as protests erupted across the country against the new citizenship law, but the years that preceded this iconic piece of work are telling of the person he finally became.

Faiz once said, “It’s not enough just to be familiar with the language, you also have to know its mood.” Although he knew Arabic and Punjabi, most of his work is in Urdu,but his audience is international. He even wrote about Palestine and Africa. He wrote about wherever he felt there was oppression, and a need to lend his voice. Faiz’s years at Pakistan Times were barren of any poetry, but in his editorship, he “assumed the stance of opposing the governmental policies of Liaqat Ali Khan, especially on issues concerning Pakistan’s association with the British Commonwealth and the country’s pro-American, anti-Russian Cold-War policies”.

ThePrint takes a look at the life of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, on his 109th birth anniversary, as editor-in-chief of Pakistan Times and the poetry he wrote in prison.

Pakistan Times

When Mian Iftikharuddin — the owner of Progressive Papers Limited — requested Faiz to be the editor-in-chief, the poet was hesitant, having had no experience at a newspaper. But Iftikharuddin was convinced that a week-long mentorship under Brigadier Desmond Young would be enough for Faiz to learn the ropes. The newsroom was buzzing, the excitement was palpable, people would turn up early and stay till after hours.

“Faiz was always on the lookout for bright and talented young writers who were courageous in their writing and displayed some freshness of thought,” wrote Ali Madeeh Hashmi — Faiz’s grandson — in his book Love and Revolution: Faiz Ahmad Faiz.

The editorial policy of Pakistan Times was based on Jinnah’s numerous speeches which focused on a democratic Pakistan, the welfare and progress of its people, equal representation of all identities residing in the country, among other such issues.

Faiz believed “the real success of a newspaper depends on its reporters who chase after the news on the streets, from one office to another, from one desk to the next”. The lead story in Pakistan Times was often international news, to which Faiz used to say, “Your country is more deserving of your attention.”

Danish Husain — actor, poet, Dastango and theatre director (who had a small role in Nandita Das’ Manto, in a court scene that also featured the character of Faiz)— tells ThePrint, “Knowing Faiz, editorial (at Pakistan Times) must have been very independent and of high journalistic calibre. He was not the kind of man who would sell himself.”

Faiz was the editor-in-chief from the paper’s inception until he was picked up by the state police on 9 March 1951 and accused in the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case. He, along with 14 others, were tried on charges of treason and conspiracy against the Government of Pakistan — the punishment of which was the death penalty.

Also read: On his death anniversary, remembering the most interesting man I’ve met: Bhindranwale

Prison poetry

Thus began some of the darkest years of Faiz’s life, but some of the best years for his poetry. It was almost as if he was making up for the time he lost as a poet at Pakistan Times.

“Even though he was in jail, he didn’t lose hope. His poetry isn’t dark, it’s not filled with pessimism,” Husain tells ThePrint. He added, more importantly his “poems don’t compromise on the literary part of it nor do they slide down the melodrama spiral, and that was his greatness”.

Describing his four years in prison, Faiz said, “(It) is first like another adolescence when all sensations again become sharp and one experiences once again that same original astonishment at feeling the dawn breeze, at seeing the shadows of evening, the blue of the sky, and feeling the passing breeze.”

Urdu poetry can be classified into two schools, where classical poets follow the old registers set by Jigar Moradabadi and the like. While modern poets recreated the old style, Faiz stood in the middle, combining romanticism with revolution. Naqsh-e-Faryadi (Poems for Remonstrance) was Faiz’s first collection of poems and in it was the poem Mujhse Pehli Si Mohabbat Mere Mehboob Na Maang (Beloved, do not ask me for that love again). And it is this poem when Faiz first shifted “from traditional Urdu poetry to ‘poetry with purpose’”. The first stanza reads typically like a love poem:

Mujh se pahlī sī mohabbat mirī mahbūb na maañg

(Love, do not ask me for that love again.)

Maiñ ne samjhā thā ki tū hai to daraḳhshāñ hai hayāt

(I thought as long as I have you, life is radiant)

Terā ġham hai to ġham-e-dahr kā jhagḌā kyā hai

(What pain could rival the pain of being without you)

It is then followed by a stanza about grave social injustice:

An-ginat sadiyoñ ke tārīk bahīmāna tilism

(The dark and savage enchantment of countless centuries)

Resham o atlas o kamḳhāb meñ bunvā.e hue

(Woven in soft silk, satin, brocade and velvet)

Jā-ba-jā bikte hue kūcha-o-bāzār meñ jism

(Bodies everywhere being sold in markets)

Khaak meiñ luThḌe hue ḳhuun meñ nahlā.e hue

(Bodies soaked in the dust and sunk in the blood)

Also read: Of caste struggles and women empowerment, a look at Premchand’s short stories

A similar trend is seen in his Lauh-o qalam (Slate and Pen):

Asbāb-e-ġham-e-ishq baham karte raheñge

(We shall gather reasons for the sorrows of love)

Vīrāni-e-daurāñ pe karam karte raheñge

(And so remove the desolation of the times.)

Haañ talḳhī-e-ayyām abhī aur baḌhegī

(Indeed, the bitterness of days will now increase further;)

Haañ ahl-e-sitam mashq-e-sitam karte raheñge

(Indeed, the people of tyranny will continue their tyranny.)

The poem weaves in and out of the multiple imageries of the slate and pen. In saying “the desolation of the times”, Faiz perhaps refers to Pakistan’s situation back then and also acknowledges the continued tyranny and the uphill battle they had to face to defeat it. Moving closer to the end of the poem and harking back to a “beloved”, Faiz writes:

Baaqī hai lahū dil meiñ to har ashk se paidā

(If blood remains in the heart, then we will make from every)

Rañg-e-lab-o-ruḳhsār-e-sanam karte raheñge

(Tear, colour for the lips and cheeks of the beloved.)

Another prison work of his that is often overlooked by translators is Sísõn Kã Masïhâ Koï Nahïn (There Is No Savior of Crystals). Writing about post-Partition disillusionment, Faiz does not hold back while reflecting the horrors of all that India and Pakistan were “robbed” of. Unlike the two poems mentioned above, while this one uses imagery, it does not switch between a beloved and the country:

Phir duniyā vāloñ ne tum se

(People of this earth robbed you)

Ye sāġhar le kar phod diyā

(Of the goblet, then shattered it)

Jo mai thī bahā dī mittī meñ

(Letting its wine run in the street)

Mehmān kā shahpar tod diyā

(They broke the guest’s bright wings.)

“Because of Faiz’s romanticism of revolution, his poetry acts like a balm,” explains Husain. Faiz’s revolution doesn’t look like violence and gore, it looks like hope.

An offer to return

Four poetically-rich years later, Faiz was released from prison. When he came back, he was offered his old job at Pakistan Times — which was now owned by the government — to which he said, “Principles are not for sale. Tell the government to hand the newspapers back to Progressive Papers Limited and let us run them the right way.”

Listing the three reasons behind the degeneration of Pakistani journalism, Faiz said, “It (journalism) became a business, second reason is that people became afraid (after Mohammad Ayub Khan seized Pakistan Times in 1958), and third was that a sense of pride in your profession was lost.”

Also read: Modi’s India unhappy with protesters singing Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge. Zia’s Pakistan was too