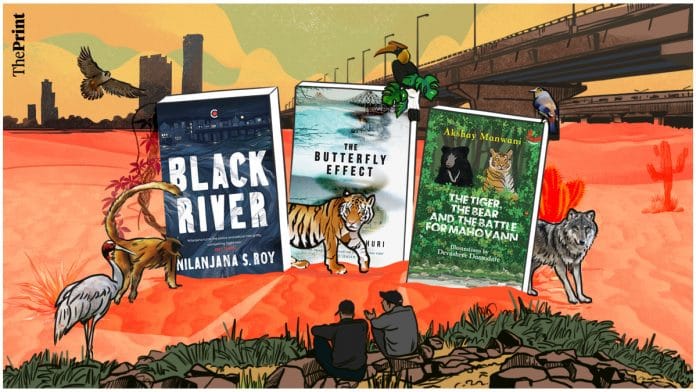

New Delhi: For the most part, Delhi turns its back on her, staining her swollen body with its ashes and garbage and sewage, choking her with the city’s waste, its discards, its corpses and diseases,” writes Nilanjana Roy in Black River.

Roy is talking about the Yamuna, rendering the river alive as she describes its death. This — anthropomorphism — is one of the features of the growing genre of climate fiction. Rising environmental concerns and the planetary crisis form the nucleus of the narrative.

Amitav Ghosh is credited with being the first Indian English-language writer to venture into the seldom talked-about space with his 2016 book, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. The non-fiction book assessed representations of climate change in popular imagination, asking why and whether it had remained elusive in story-telling.

The Great Derangement did not open the floodgates, but the trickle of climate fiction is now a steady stream catering to an increasingly aware and curious audience.

The rise of cli-fi

In its more one-dimensional avatar, climate fiction falls under the blanket of speculative fiction. In 2020, American sci-fi writer Kim Stanley Robinson published the canonical ‘cli-fi’ book The Ministry For The Future, about an organisation that advocates for the rights of future generations as though they had the same validity as the present generation.

Now books being published are in various categories under the label— from literary fiction where an exhausted river steers the characters’ arcs to dystopian fiction that immerses the reader into extremes emerging from inaction. There are even children’s books about the environment.

“I have just read and loved a manuscript looking at a post-climate change world where the coasts no longer exist and the war on water has created complete destruction of law and order and governance. Perhaps this kind of dystopian fiction is the best way to awaken people to the urgency of the climate crisis,” says Tarini Uppal, senior commissioning editor at Penguin Random House India.

But the question remains – is this a new phenomenon?

“The climate crisis has almost always had a shadow presence of some kind in our literature—don’t we read of droughts, urbanisation, receding monsoons, our unbreathable air and undrinkable water in so many Indian narratives?” adds Manasi Subramaniam, editor-in-chief at Penguin India.

Yet, as the immediacy of the crisis intensifies, more and more books are being tagged as such.

Also Read: What’s eco-anxiety? It’s caused by climate change and can be combated

The instinctive writer

Published in November last year, Black River follows Rabia as she moves next to the Bhalswa Landfill in Delhi’s Jahangirpuri, and searches for ways to build a life on the outskirts of fumes and toxicity.

As for the ‘why’ behind Black River, Roy calls writers “highly instinctive creatures”.

“It [the book] started out with curiosity about the Yamuna – a place that the city had turned its back on,” she says.

“Climate change is intimate,” she adds, saying that writing a book that emerges from neglect, and the missteps we have taken changes your sense of the city. Giving the example of one of her characters Khalid, whom she describes as a river man, she says, he knows the river down to its innards – it is his means of sustenance – and so he feels its every change viscerally.

“The river is at the heart of the book. It is about a colony within Delhi. The history of the Yamuna is bound with the promise of what nature offers you in your city,” Roy says.

By giving non-human life importance, the human race becomes less arrogant, less uncaring. “I felt an urgency while writing. Each time I went back to check a certain detail, between 2017 and 2020, so much changed. Families moved out, floods were getting worse. Living in Delhi is like living in fast-forward,” says Roy.

As she finished the final draft, she found that the river had changed again. “I got the sense I was dealing with a mighty force. We’re seeing what happens when we mess with natural forces, like in the case of Joshimath,” she says.

“The Yamuna dances, revealing a glimpse of what she might have been without the city’s discards,” reads Black River indicting the citizens of Delhi for their apathy and disregard, which is another notable feature of climate fiction. The reader is not just made aware of the crisis, but also made to feel uncomfortable for contributing to it, directly or indirectly.

“Climate fiction is part of a larger concern that affects a lot of people, though it may not necessarily be expressed in the same form,” says Karthika VK, publisher, Westland Books

Books from the genre, including Black River, function as microcosms, weaving together various issues that plague the world today.

“It is a creative reflection of the realities of our time. Today, it is a prerequisite to be concerned with what’s going on.” says literary agent Kanishka Gupta.

Roy, Karthika, and Gupta, all point towards Janice Pariat’s latest book, Everything the Light Touches, described in The Guardian as “a dialogue with nature” as an example of this style of writing.

The main character Shai, inspired by Goethe’s radical botanical writings, travels to the forests of the lower Himalayas, full of unanswered questions about politics and sexism in science. She learns that issues in science are beyond the dismissal of women: they’re also about “how botanical knowledge was sought, gathered, processed, gleaned – and whose methods were considered sound and ‘scientific’.”

Also Read: What books did ThePrint’s columnists love in 2022? They should be on your list too

Climate fiction for children

Books are also being written as a means to document, as the erasure of entire species and ecosystems becomes a reality. Environment and wildlife activist Akshay Manwani seeks to inform a younger generation of what once existed, by inculcating curiosity and a sense of wonder in children.

“Children’s minds are like sponges,” he says. His book, The Tiger, The Bear and The Battle for Mahovann pledges to give information that is specific rather than overload young minds with the vagaries of life and nature.

Climate fiction, as marketed for children, doesn’t necessarily require the loudness climate discourse typically calls for. Instead, the stories crafted can have subliminal messaging — of seeing and respecting animals the way one would humans, of being sensitive to one’s external environment, and living more sustainably.

“I wanted to tell a story that captivates and introduces children to the vastness of India’s biodiversity, not just the country’s flagship species,” says Manwani. Children’s literature fulfils a dual role, by simultaneously educating and entertaining.

“Every book, every video, every photograph is archival footage,” he adds.

He believes it is important to not dabble in “generic terms” when it comes to children. “If we tell them, this is not just any ordinary langoor, but the golden langoor or this is not your typical bird, but the great Indian hornbill – their minds are piqued,” he says.

As is implied from its title, Manwani does focus on so-called ‘flagship species’ like the tiger, which already has a number of mammoth projects in place for its conservation in the subcontinent. But, he uses the magnetism of the tiger to lure his reader in. The book ends with a six-page glossary, detailing the host of ‘side characters’. The 35 species of birds and animals listed include the peregrine falcon, the sarus crane, the Indian grey wolf, and the silver-breasted broadbill.

A number of parents and children have sent him feedback, telling him that they learnt something about the spectrum of animals that India has to offer.

The fact that there are multiple identities flourishing under the same ‘genre’, reflects the malleability of climate fiction.

“There is a lot more reading in the space. It is something that is only going to grow. Currently, it is nascent in a lot of categories. But, it is convenient to put a label on it. Labels attract the reader,” says Karthika.

Also Read: Ashneer Grover, Ankur Warikoo books sell like hotcakes. Startup guys new India’s storytellers

Regional exploration

While climate fiction is emerging as a label in English-language writing, regional writers have also been exploring ecological questions and the now fraught relationship between humans and non-humans.

“I think of books like Rising Heat by Perumal Murugan, translated from Tamil by Janani Kannan, or Budhini by Sarah Joseph, translated from Malayalam by Sangeetha Sreenivasan. Both put the environment at the centre of the narrative, calling out the devastation wrought upon the planet by ceaseless, single-minded development or urbanisation in the name of progress,” says Penguin’s Subramaniam, pointing out that there exists a body of environmental literature outside of English.

There’s poetry as well.

“One recent book that immediately springs to mind is Hunchprose by the truly gifted Ranjit Hoskote, which closely interrogates human greed and its impact on the planet,” she adds.

In The Great Derangement, Amitav Ghosh attributed the gaping hole of environmental writing in Indian fiction in English to “the grid of literary forms and conventions that shaped the narrative imagination in precisely that period when the accumulation of carbon in the atmosphere was rewriting the destiny of the world.”

This is despite having two notable works — The Hungry Tide (2004) and Gun Island (2019) — that fall neatly under the category of climate fiction. The former closely inhabits the Sundarbans and reinforces the idea of human fallibility in the face of nature while the latter ticks every climate-fiction box. It places global systemic issues, like the ensuing onslaught of refugees from consequently inhabitable regions, in the foreground of a planet in flux that subsumes and aggravates everything else.

However, Ghosh dislikes the term being used to describe his work, as he feels it is just one of the many interconnected realities that he wants to represent.

Are there any readers?

According to publishers, the market for speculative fiction in India is limited, with fewer writers and readers, as compared to the West.

However, outside the big five publishers and their writers, a tiny cli-fi movement has been brewing. Rajat Chaudhuri, who used to work in activism before switching to writing full-time, has been working with the genre since 2013.

Chaudhuri’s Butterfly Effect, published by Niyogi Books in 2018, is based in Kolkata. The plot kicks off with a lab accident brought about by a genetically modified rice seed. The ensuing events are then aggravated by climate change. Chaudhuri straddles utopian and dystopian writing, saying that grief and sorrow can also motivate people.

He also edited a volume of short stories, Multispecies Cities: Solarpunk Urban Futures.

“Cities are alive, shared by humans and animals, insects and plants, landforms and machines. What might city ecosystems look like in the future if we strive for multispecies justice in our urban settings?” reads the introduction.

His next book, also due to be published by Niyogi Books, probes the act of splitting up. As the world ‘splits’ into two, so does its protagonist, torn between his high-consumption lifestyle and his identity as a climate activist. It picturises three major climate change-wrought events — smog in Delhi, a landslide in the Himalayas, and desert storms in Rajasthan.

“I have started seeing more and more manuscripts coming in that focus on the environment and climate change but the market for novels around these themes is still very small,” says Penguin’s senior commissioning editor, Tarini.

Chaudhuri too admits that readership needs to be greater. “We need a Chetan Bhagat of climate fiction,” he jokes.

There is also the presumption that non-fiction may capture the nuances of the crisis better. But, climate change is still a human phenomenon, built and nurtured by one race. And this effect — “the human effect” — can only be captured through fiction, argues Tarini.

And as the climate crisis unfolds, with closer proximity and greater intensity, fiction might just be our final place of residence.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)