When Sabyasachi Mukherjee returns home to Kolkata this March after his celebrated show in Mumbai, there is one entry in his calendar that he is most unlikely to miss: a walk-through at a textiles exhibition in the city. The exhibition recounts how undivided Bengal clothed the world for centuries across the colonial capitals of London, Paris, Lisbon and Copenhagen – just as Mukherjee is doing today, on an even bigger canvas, carrying forward a legacy that once adorned even gladiatorial Rome.

Taking him on the walk-through will be Darshan Shah, a Kolkata‐based textiles entrepreneur who has helmed the exhibition titled Shared Legacy. Shah, who has been working on Bengal textiles for decades from the Weavers Studio Resource Centre, is on a mission to make her passion for Bengal’s textiles a shared passion, spurred by the meagre share the state’s fabrics received at the seminal exhibition at London’s V&A Museum in October 2015, titled Fabrics of India. “Bengal’s textiles made up barely five to seven per cent of that show, completely disproportionate to their historical impact across the world,” she says. “Textiles from India’s West and Coromandel coasts are superb. But Bengal textiles must be given their due. We must turn the spotlight on them and restore their lost splendour.”

The muslins, silks and jamdanis from the undivided state were legendary. French traveller François Bernier, who arrived at the court of Aurangzeb in 1656 and travelled the country for 12 years, wrote of Bengal’s muslins that they were so delicate they could disintegrate in no time. In his book, Travels in the Mogul Empire, he described karkhanas – or factories – where hundreds of artisans worked manufacturing “…silk, fine brocade, and other fine muslins, of which are made turbans, girdles of gold flowers, and drawers worn by Mughal females, so delicately fine as to wear out in one night.”

Bengal’s textiles were travelling the world for thousands of years, reaching ports in the Red Sea, as recorded in a Greek logbook of ports and sailing itineraries called the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea in 100 CE. Textual references also exist of their trade in the east – to Indonesia, the Philippines, China and Japan. However, the boom for Bengal textiles began after the Portuguese dropped anchor at Saptagram (also known as Satgaon) in Hooghly district in the early 17th century. The Dutch and the French soon followed, later joined by the British and the Danes. The demand for Bengal’s textiles soared and spurred supply, the boom peaking until the industrial revolution in England in 1760, which subsequently flooded the world’s markets – including India’s – with cheap machine‐made fabrics.

The Portuguese colcha

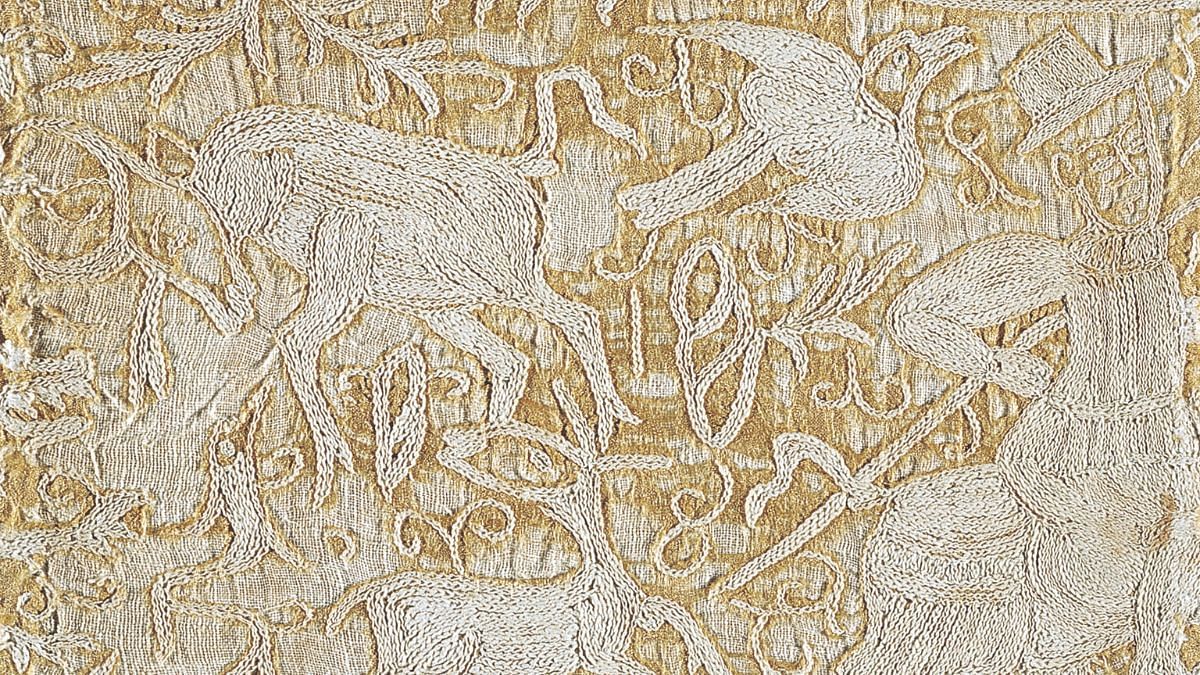

The oldest exhibit Sabyasachi will see at the exhibition, which opened at the Kolkata Creative Centre on 2 February, is the colcha – the finely embroidered wall hangings or quilts that the Portuguese commissioned the skilled embroiderers of Saptagram to create for the Lisbon market. Darshan Shah’s Weavers Studio, which has been collecting textiles for years, has put on display a fragment of a colcha on loan from the TAPI collection based in Surat. Two other colchas have come from collections across India.

“The heavily embroidered colchas are a testimony to the indigenous skills of Bengal’s artisans,” explains Subham China, a researcher at the Weavers Studio Resource Centre. The colchas sometimes featured a frill or tassel along the edge, added in Patna. They were often given a finishing touch in Goa – the original Portuguese colony in India – from where they were shipped to Lisbon. “There are different opinions about the colchas. They are sometimes labelled as a product of Goa,” says China. “But we believe their provenance is Bengal’s Saptagram.”

According to the Textiles Research Centre at Leiden in the Netherlands, “colcha is the Portuguese term for what in the English language is called a Bengalla.”

Haji rumals

Silk-on-silk embroidery – similar to that used for colchas, primarily the chain stitch – was employed to create Haji rumals, which were tied around the headgear of those returning from Mecca after the Hajj pilgrimage. These rumals were popular during the Mughal period and were exported widely to South East Asia.

“In his two authoritative volumes, Indian Textiles, historian and co-author John Gillow records how Damascus in Syria also produced Haji rumals. But the workmanship was poor, so artisans from Bengal were supposedly taken to Syria to give the products a good finish,” says China, who—while pursuing his PhD in international relations—has been researching how skilled textile artisans from Bengal were traded as slaves not only to Damascus but to many other parts of the world.

Muga skirt from the Netherlands

The prospect of a rich trade in textiles led the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to set up factories at 15 different locations across deltaic Bengal, with headquarters at Chinsurah in 1656. They sold cottons and silks produced in their Bengal factories to the world, including Japan. Late in the 17th century, “changes in fashion, including the lavish use of silk fabrics for ladies’ clothing and a new type of gown worn by both men and women, contributed to the increase in Bengal silk imports by the Netherlands,” according to authors Ebeltje Hartkamp-Jonxis and Byapti Sur in the book Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy, published by MAPIN as an integral part of the exhibition.

This loose gown, usually made from high-quality silk, was known as the Japonsche Rock (Japan gown) and was worn as an informal dress or a garment of distinction. In England, the same attire was called a banyan, though it was very different from what we in the subcontinent understand by the term today – in India, a banyan is a vest worn by men under their shirts.

For formal gowns and skirts, Dutch women used rich silks from Murshidabad. One such skirt, made of Muga silk fabric around 1781–82, has been lent to the Kolkata exhibition by the family of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee of Singapore.

Muslins

Bengal’s legendary muslins – so fine that a six-yard saree could fit into a matchbox – are rarely seen in person today. This makes the muslin gown on display at the exhibition a visual treat. Made of fabric woven in Bengal sometime in the late 18th century and finished in France, the gown is ruched, embroidered, laced and full-sleeved, serving as a reminder of tales about how Aurangzeb reprimanded his daughter for arriving in court apparently wearing nothing, when in fact she was clad in a dress made of seven layers of muslin. There are many versions of this story.

The dress on display was acquired by Darshan Shah’s Weavers Studio Resource Centre just six months ago at an auction in London for Rs 40,000.

The French colony of Chandannagar in Bengal’s Hooghly has a short history – established in the 1680s and captured by the British in 1757 – yet it was a busy trading post, and the fine textiles it sent back home set fashion trends in the fashion capital of Paris.

Dark stories

There is much more for Sabyasachi to see – many stories that Darshan Shah could share with him during her walk-through – including a dark tale of the forced migration of Bengali artisans, enslaved by Portuguese and Dutch colonisers and sold to traders who were willing to pay for their skills.

Indeed, women embroiderers were in demand in Cape Town, which was colonised by the Dutch, and in Mexico, colonised by the Spanish, who bought them off Portuguese traders from the east. “Shiploads of Bengali artisan slaves, men and women, were off-loaded at Acapulco and sent to work in textile factories,” says China. “Many experts have found similarities between Bengal’s kanthas and the rebozos or shawls of Mexico,” he adds.

Bengal’s textiles travelled far – not solely by trade.

Recording history

The exhibition runs until the end of March. For those who have missed it so far, there is still time to visit. Alternatively, there is the beautifully produced book Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy. You might mistake it for a coffee-table book – it is large and 360 pages thick – yet it is truly a bridge between that and a heavily academic tome, full of photographs of exhibits from across the world, their stories, maps and historical details, all of which stand as testimony to the global presence of Bengal’s textiles from 1600 onwards.

Sabyasachi may have difficulty lugging the book around – it is heavy. But both the book and the exhibition open new doors in an ambitious journey to chronicle, archive, revive and restore Bengal’s textiles to their original splendour, giving them a fresh lease of sustainable life.

(Edited by Prashant)

An excellent article. Such articles show that Ms. Banerjie is indeed capable of quality journalism.