Kanpur: A mound of trash in Kanpur’s Parmat Mandir is essentially a deconstructed bouquet—rose petals, jasmine, and marigolds—that is sniffed and eaten by goats and monkeys. Or ends up immersed in the Ganga, accompanied by plastic cups and packets of chips.

But that was before the entry of Phool in 2016, a Kanpur-based start-up that turns discarded flowers into incense cones, sticks, and essential oils. Courtesy 32-year-old Ankit Agarwal, waste-picking in temples—particularly those with throngs of frenzied devotees—has been given a neat makeover.

“I had seen my parents, grandparents, and everyone else putting waste into the river. I can’t do anything about the effluents being poured into the river and there’s no data on how much waste is produced,” said Agarwal, an IIT Kanpur graduate. “But there was one problem I could solve.”

It’s led to a self-contained flower economy in Kanpur that’s benefiting everyone who’s involved—from the purchase to the disposal to their metamorphosis. Phool employs over 300 women, who make products for the wellness-obsessed, including customer-turned-investor Alia Bhatt. Now, they’re also experimenting with a faux leather alternative made from flowers.

For the women of Kanpur and neighbouring villages, Phool has been a game changer—they’ve upskilled in ways that they never imagined. Forty-year-old Preeti Shukla joined the Phool factory because it had an eight-hour shift, not the usual twelve. With the extra hours in hand, she could run her household more efficiently and spend time with her children.

“From picking up flowers at temples, I now work in the factory’s D2C section,” she said. “I’m working on computers, managing orders, and teaching the ropes to women who’ve just joined.”

Most of the flower waste doesn’t make it into the blue dustbins parked outside the temples by the Phool team. But every single day like clockwork, their loading team arrives on the scene. They stay for hours, as the morning winds into the afternoon—mechanically piling tonnes of garbage into trucks.

They’re then taken to any of Phool’s three units in Kanpur where they’re separated, dried, pulverised, and distilled. From the muck emerges a dough—essentially raw fragrance. This is the foundation for the incense sticks and cones made by Phool. It’s a simple formula that’s been amped up.

“The dustbins outside the temples were our major capital investment,” said Nachiket Kuntla, Phool’s Research and Development head. As for the rest of it—“it’s basic chemistry”.

This application of basic chemistry has resulted in a company with a reported annual revenue of Rs 28.6 crore, with investors like Sixth Sense Ventures, India’s first domestic consumer-centric fund. In 2022, Sixth Sense invested $8 million into Phool.

By creating a flower-based leather, which Kuntla estimated should be ready by the end of the year, they’re upping the ante and expanding the humble temple flower’s potential. The room it’s being built in isn’t too different from a science lab. There’s a hydraulic press, vats of a mysterious oil, and a number of employees waiting for their eureka moment.

Also read: Why are South Indian temples larger than ones in North? Answer isn’t ‘Islamic invasions’

Getting temples on board

Back in 2016, Agarwal had a friend from the Czech Republic visit his hometown of Kanpur. He was at a complete loss in terms of what to show him.

“In Kanpur, there aren’t a lot of places to take people to,” he said. “So I took him to the banks of the Ganga.”

They visited Parmat Mandir—where the duo was aghast. His friend counted at least 147 people who bathed in the visibly filthy holy river. It wasn’t just devotees, tonnes of flowers went in too. On average, at least three to four tonnes of flowers are collected each day from Parmat Mandir and its neighbouring temples in Kanpur. That sight sparked the idea for this lucrative, sustainable act of goodwill, which has trudged into other parts of the country too.

Today, Phool operates in six cities. The company has signed MoUs with major temples across the nation—including the Ram temple in Ayodhya, Kashi Vishwanath in Banaras, and the Jagannath temple in Puri, Odisha.

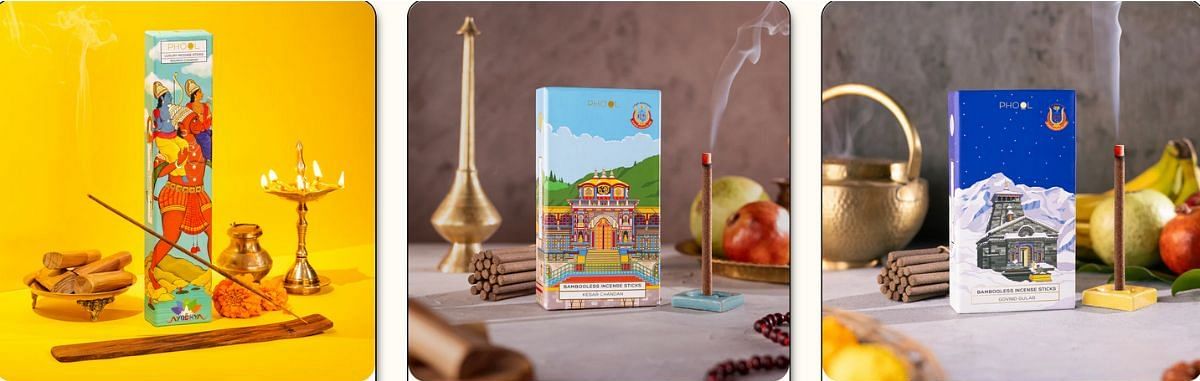

There are temple-specific packages, which according to Kuntla, are a big crowd-pleaser. Their Badrinath set features an illustration of the temple’s facade. The Ayodhya-specific package features Ram and Laxman on the shoulders of Hanuman. “This creates consumer interest,” he said.

Even their non-temple-specific products have distinctive packaging, with intricate illustrations depicting temples, and women with flowers in their hair.

“We used to have jute packaging. But why shouldn’t sustainability be colourful?” said Agarwal.

They’re certified fair trade and organic by French company Ecocert, one of the most reputed organic certification bodies globally. It’s a seal of approval for their sustainability practices, for which they’re audited three times a year.

At the time of inception, all they sold were incense sticks and cones. But owing to the popularity of their products, they expanded into essential oils, soy-based candles, a mosquito repellant, and all things festive. Natural Holi colours and plantable patakas, the most damaging elements of India’s festivals, have been reinvented in a way that’s planet-friendly.

“All of our growth has been organic. The product is pocket-friendly and a talking point. We’re not launching five products every month. We’ve gone against the grain in terms of the D2C industry,” said Agarwal. “There’s consistency. We have people who’ve been buying regularly for the last 5-6 years.”

But before gaining customers, they had to get permission from temple authorities. And they weren’t ready to jump on board.

According to Swatantra Dwivedi, who supervises the loading process at Parmat temple, they faced opposition from the priests—waste and incense were two completely separate domains for them. They were suspicious about the final product, and how their waste would be used.

But once they agreed and things began rolling—the floodgates opened. And it became far easier to convince other temples once they had bigwigs like Kashi Vishwanath and Ayodhya under their belt.

Also read: When did large Hindu temples come into being? Not before 500 AD

A women-only workforce

There’s a steady din that echoes through Phool’s factory in Kanpur—boxes of incense are being piled onto a mini conveyor belt, addresses are being pasted, packages are being sealed, and there’s a murmur of conversation. This is a war room: the factory’s D2C section where online orders are processed.

It wasn’t a deliberate move, but the stream of chatter is women-only. Agarwal found that men were reluctant to work with flowers, to perform the supposedly menial task of collecting and drying flowers.

When Shukla joined, for the first couple of years, she only separated and put flowers out to dry. Then she started making incense sticks—and finally graduated to packaging. Now, she has a more supervisory role and instructs newer inductees on what their roles are.

“I didn’t think I’d be doing this kind of work because I haven’t studied enough, and because of household pressures,” she said frankly. “In today’s times, well-qualified people aren’t getting jobs, so what hope did I have?”

Chitra’s trajectory is similar. She started working at Phool during the Covid-19 pandemic and has undergone the same transformation—from working to teaching other women. She’s from UP’s Auraiya district, but now, due to her work, she has taken a house on rent in Kanpur itself.

There’s a camaraderie on display at the Phool factory. There’s a company bus, on which the women travel back and forth together each day. Many of them said it was a relief to work in a factory that primarily consists of women, adding that they “feel safer” as a result.

They’re soon going to be swept up by the festive season. Raksha Bandhan is fast approaching and they’ve had orders for rakhis since July. A group of three women sit on the floor, methodically separating plantable rakhis, each of which has a seed inside. They also receive massive corporate orders, which go up to about 10,000 boxes.

It’s a system that’s beneficial to all. In a dingy room at the top of the temple, the priests sit together, and one of them rolls a joint. They appear to be completely relaxed.

“Recycling is good. Before Ankit Agarwal, there was pollution in our temple,” Vashishth Giri Maharaj declared, seconds before he closed the door.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)