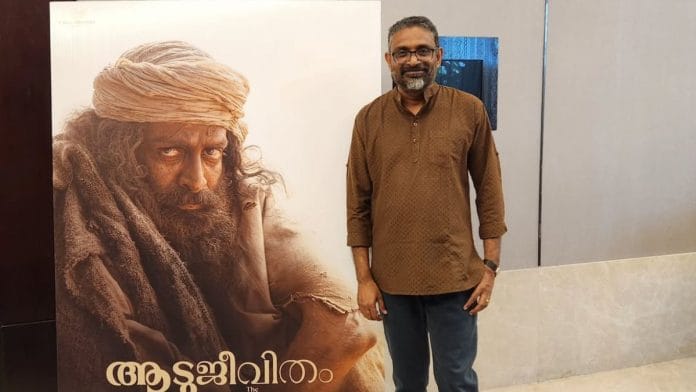

Kozhikode: Author Benyamin is riding on a career-high. His magnum opus on migrant life Aadujeevitham was made into a blockbuster movie of the same name in 2024. At this peak, most other writers would be keen to get the ball rolling on more film adaptations of their works. But not him.

“Cinema is a collective process. It changes according to the whims, pockets and locations of multiple people. Literature is not like that, it’s a solitary process. You only have to satisfy yourself. You’re the king of it,” the author told ThePrint.

But fame and readership are not battles that are won alone. Benyamin was part of a cohort of authors who gained prominence in the 2000s in Malayalam literature—writers who brought people back to their books in the time of the internet. Benyamin attributes his success to authors such as Subhash Chandran, TD Ramakrishnan, KR Meera and E Santhosh Kumar.

“We used language the youth understood, and topics they related to,” Benyamin said.

He is currently in the middle of a serialised novel—Mulberry—chapters of which are released weekly in the magazine Mathrubhumi Azhchappathippu. He plans to publish it as a book once it is complete.

It’s only the second time Benyamin’s work has appeared in a serialised manner. The first was Akkapporinte Irupathu Nasrani Varshangal (2008), published immediately after Aadujeevitham. Coincidentally, Mulberry follows the release of the film adaptation.

The story is based on the real-life author, poet and publisher Shelvy who began Mulberry Publications with his friend Daisy whom he later married. The publisher introduced a host of foreign writers to the Malayali audience through translations and published an array of Malayalam writers. Benyamin—using the voices of these writers, real and fictional—tries to unravel the enigma that was Shelvy, who died of suicide in 2003.

In it, the author does what he does best—take compelling figures from real life and place them in semi-fictional narratives along with completely fictional characters.

Acknowledgment or exploitation

Benyamin’s deft weaving of fiction and non-fiction is not without its critics. Aadujeevitham—both the film and the book— which heavily borrows from the life of migrant worker Najeeb and his struggles in the Gulf, came under the scanner for being ‘exploitative’.

The author vehemently rejects the label. “I didn’t write Aadujeevitham to show Najeeb’s life. It wasn’t a biography. I’ve used parts of his life to bring life to a larger story—how people are exploited in the Gulf, what it’s like in the desert, how it feels to live alone,” he said.

He has publicly, and constantly, credited Najeeb, which Benyamin sees as a symbol of his integrity as an author. “Najeeb is the core of the story. That is why he is credited so openly. I could’ve hidden him and his life, but that goes against my responsibility as a writer,” Benyamin said.

The contention many have is that the novel includes morally grey scenes, including one that implies the protagonist has sex with a goat. The lack of clarification on which parts are true and which are creative embellishments has led to some embarrassment for Najeeb.

When questioned, Benyamin falls back on his refrain. “Whenever an author writes a story, it’s influenced by the many prototypes of people you see in your life. So I think anyone who refers to this as exploitation doesn’t know what literature is,” he said.

Also read: ‘If Instagram was there in the ’80s, my poet friends would still be alive,’ says Jeet Thayil

Rise of Gen Z readers

Benyamin came to literature late in life. He started reading in his late twenties, it was driven by the loneliness he felt as a migrant in the Gulf.

“There are more avenues of entertainment now. Even when you’re physically alone, you have social media. Maybe that’s why there’s still not enough people coming to literature,” he said.

But he refutes the idea that Gen Z doesn’t read. He points to numbers to prove it.

“Just look at book sales. In my childhood, a good book would sell around 1,000-2,000 copies. Now that number is in lakhs,” he said.

Benyamin added that you can see it not just in sales but also in the crowds at literature fests. This year’s Kerala Literature Festival, held in Kozhikode from 23 to 25 January, was attended by over six lakh people.

“There is a new generation of people who truly value reading above all else,” he said. And while Gen Z treats writers like rockstars, Benyamin said they still don’t understand the amount of work that goes into writing.

The question he gets most from the generation is how he can write books that are so long and detailed.

“The problem is that Gen Z has seen a lot of instant success. You post a reel, it gets millions of views and that catapults you to fame. They think writing is also like that,” Benyamin said, adding that a five-year timeline for a novel is unthinkable to the young generation.

Benyamin sees this slow process as a blessing. It’s not like other avenues of fame such as sports and cinema where your stardom can fade as you age. Writing has no retirement age.

“If you’re a sportsperson, you retire by the time you’re 30, whether you’ve achieved legendary status or not. But when you are in literature, you are a very junior person at the age of 30. Age and experience only add more value to your work,” he said.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)