New Delhi: Filmmaker Wim Wenders inserts a healthy dose of fiction into his non-fiction. This welding of fact and fiction is his way of distilling the world. The result is a narrative that’s immune to easy categorisation.

“I love everything of reality that enters into fiction and every little piece of story that enters reality. I think it’s more interesting. Sheer fiction bores me to death,” said the 79-year-old auteur to an audience that was hanging on to every word.

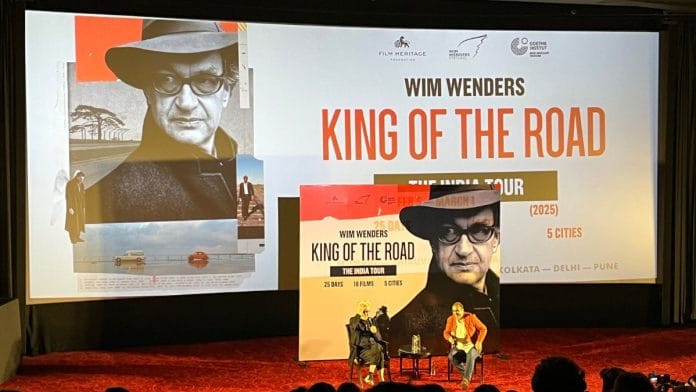

Wim Wenders’ India tour finally arrived in Delhi, and the ‘King of the Road’ was candid –– laying bare tricks of the trade, the forces that have shaped his work (the personal and the political), and challenges that invariably arrive in the form of dissemination and distribution.

In conversation with the director of the Film Heritage Foundation, Shivendra Singh Durgapur, Wenders’ masterclass was exactly what it set out to be. Except, this wasn’t Wenders explaining camera techniques or the semantics of style. It was a no-holds-barred conversation with the Palme d’Or winner and one of the architects behind the German New Wave.

Wenders started out as a painter, attended a film school that didn’t have a camera, and watched a thousand films at a cinematheque in Paris. His initial films take inspiration from American Westerns, particularly the work of Anthony Mann. But the filmmaker who influenced him most was Yasujiro Ozu. The Japanese filmmaker is known for his meditations on family life. Most of his films never made it to Europe, as they were typecast for being “too Japanese”.

Strong sense of place

What separates Wenders from big studio directors and images of Hollywood glamour is his commitment to place –– all his films are shot on location. Whether it’s the oppressive highway heat in Paris, Texas, or Cuba in Buena Vista Social Club, space forms an essential catalyst for the unfolding of every arc.

“You didn’t need the script if you had the road. The itinerary is the script,” said Wenders. “I’m not afraid to shoot somewhere I’ve never been. My most important specificity is place.”

He went on to say that he enjoys Indian films because they too have “a strong sense of place”.

Wenders has spent a significant amount of time on the move, and describes himself as having dual professions –– filmmaking and traveling –– both of which are inextricably linked. He was born in Dusseldorf in 1945, the year of the atomic bomb. He was brought into a world and a country that was grappling with its past, suspended in memory.

“You have no idea what the past is; [the country] was so frantically trying to build the future,” said Wenders. The past was taboo. Nobody spoke of it. Eventually, you realise that’s because they belong to that time.” He had a math teacher with a toothbrush mustache –– an homage to Hitler.

This fueled within Wenders an unmistakable desire to leave Germany. And so he did. His first foray into travelling.

Also read: 25 Thai dancers and 6 musicians recreate Ramayana. It’s universal

Storytelling to storyselling

Wenders shoots all of his films in continuity. There’s no middle filmed before the end, with the beginning sandwiched between.

“You can find the truth of the story if you live it. Existentially, you’re much more involved than you would be if you shoot zigzag,” he explained.

It also permits his actors to inhabit their characters more wholly. This less-practiced approach, an almost spontaneity carries on to the screen.

“There’s nothing worse than an actor who’s always fantastic. I don’t know more than them,” said the Tokyo-Ga maker. “Stories shouldn’t impose themselves on characters. They should produce their life stories. I think people are free.”

Personalities and people bleed into Wenders’ fiction.

Actor Dennis Hopper arrived on Wenders’ set An American Friend (1977) straight from the Philippines, after shooting Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). He and Swiss actor and frequent Wenders collaborator Bruno Ganz clashed to the point of culmination –– a physical fight. But after leaving Wenders fuming, they ended up as friends.

“That friendship became the film. I owe them my life,” said Wenders.

It’s no surprise that people and personalities take complete hold of his documentaries as well. Responding to a question by an audience member, who asked why Buena Vista Social Club (1999) was devoid of Cuba’s politics, he said “he was witnessing a fairytale.”

“These were men who had been forgotten. And then they were playing at Carnegie Hall.”

By 1996, approximately 80 per cent of Cuban musicians had fled the country. Those who remained, members of the Buena Vista Social Club, told Wenders –– “Don’t make us say anything about Cuba. We’re going to get in trouble.”

Wenders attaches paramount importance to film history, and sees utmost value in archiving and in preserving. According to him, it’s because movies condense history, and that history is the “great fact of the future”. In an era where history is being sculpted and preened beyond recognition, cinema, for Wenders, “is an important weapon for a civilised future.”

Many of the films he spoke about are now over a quarter of a decade old. He’s experienced change, the movement from what he calls “storytelling to storyselling”. His act of subversion has been to buy the rights to all his films and restore them himself.

“They became older like I became older. They’re like my children; and there’s something of me in all of them,” said Wenders fondly of his films. “And they shouldn’t be owned by anyone –– not even me.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)