Chennai: Our genes hold the answer to the cultural and political war raging over India’s ancestry. Indo-Aryan versus Dravidian. North versus South. Prime Minister Narendra Modi Vs Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin. And based on the findings presented by Professor Raj Mutharasan, Dravidian language, and culture thrived long before the Indo-Aryan influence took hold in the subcontinent.

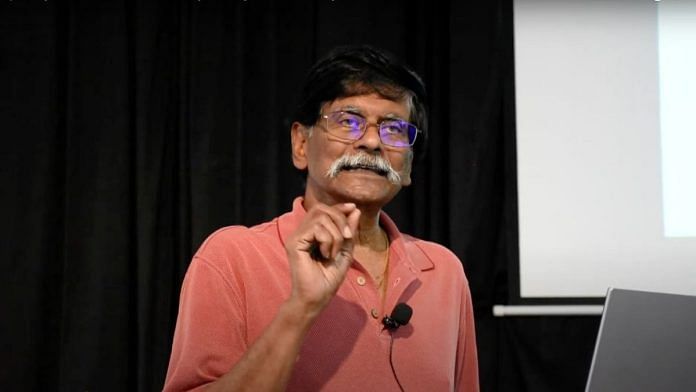

His two-hour lecture at the Roja Muthiah Research Library in Chennai on 14 February, was a deep dive into major scientific studies and research to answer one question: Who was the first Indian? It’s a hot-button topic, especially with Stalin recently announcing $1 million to anyone who can decipher the script of the ancient Indus Valley civilisation.

Mutharasan steered clear of the political debate, choosing to interrogate science—and our genes. His inferences put him on the Dravidian side of the debate, challenging the popular colonial theory that Aryans invaded and shaped India’s population.

“One of the most ancient genome markers in human history finds presence in South Asian populations, especially among Dravidian-speaking groups in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh. This shows us that Dravidian-speaking populations have direct maternal links to some of the earliest humans who settled in India,” said Mutharasan, professor of chemical and biological engineering at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

Some of the research he referenced was the 2019 Rakhigarhi DNA study, the DNA of Virumandi Andithevar, a tribal villager from Tamil Nadu, and that of the genetic origins of Andaman islanders.

“While there were cultural exchanges, genetic research shows that Tamil Nadu largely kept its indigenous Dravidian roots,” the professor said.

These findings challenge past theories that Indo-Aryans played a major role in shaping South Indian populations. Instead, they suggest that Dravidian ancestry in Tamil Nadu has remained largely uninterrupted for thousands of years, he said.

Dravidian and Tamil ancestry

To bolster his argument, Mutharasan referenced the DNA of Virumandi Andithevar. The 30-year-old systems administrator from a small village near Madurai became the face of a groundbreaking genetic study in the early 2000s after a team of scientists from Madurai Kamaraj University identified him as the “first” Indian.

This was based on his genetic marker, M130—a trace of the earliest human migration from Africa nearly 70,000 years ago. His lineage linked directly to those first migrants who likely settled in the same village a millennia ago.

“This was the first most important study that showed how genetics can shed light on the early occupants of a tiny village in Madurai nearly 70,000 years ago,” said Mutharasan. When Professor Ramaswamy Pitchappan who led the study discussed their findings back in 2008, he said that M130 was the oldest genetic marker in India, indicating that the first human settlers in India came out of Africa.

Then there’s the high-profile DNA analysis of a 4,600-year-old female skeleton from Haryana’s Rakhigarhi site, which reignited the Aryan debate in genomics, history, archaeology, and even linguistics. Put simply, there were no traces of the R1a1, or Central Asian ‘steppe’ gene or the Aryan gene.

The arrival of Indo-Aryan speaking groups – carriers of the R1a1 gene – into India has been a topic of much debate. Professor Mutharasan pointed out that the Indo-Aryans did not dilute the Dravidian lineage.

“Unlike North India, Tamil Nadu has minimal presence of the R1a gene,” he said. What’s more, genetic markers discovered at the site have also been identified in South Asian populations, including the ‘L’ haplogroup (from Y-chromosome DNA).

“Today, this gene marker is also found among South Indian populations. The possible definition of Tamil ancestry is non-R1a ancestry. Although that is also questionable because it’s not a precise statement from a scientific point of view,” the professor said.

He also cited further research based on these findings that came out from the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad. The team there found that the woman had genetic ties to the Andamanese people and belonged to mitochondrial haplogroup ‘M’. This haplogroup is linked to South Asian hunter-gatherers, some of the earliest settlers of the Indian subcontinent.

“It is also dominant in South Indian Dravidian populations. This shows a shared ancestry tracing back to the first human migration from Africa around 70,000 years ago,” said Mutharasan.

Also read: ‘The thief who stole my heart’–How pearl-laden Chola bronzes reimagined Shiva

Not so cut-and-dry

But there’s a catch. With a population of 1.5 billion, India has only one ancient genome—the Rakhigarhi excavation sample—to represent its vast ancestral history. “Moreover, all Indian scientists who have done this research have done division-based sampling, that is, based on caste and religion and not random sampling. Hence general conclusions cannot be drawn from this insufficient data, only partial conclusions are possible,” the professor cautioned.

The field of ancient DNA research has grown significantly since 2017, with over 10,000 ancient genomes sequenced globally as of today. But the bulk of this data is from Europe and Russia, whereas 500 of them are from Central Asia, Africa, and Oceania.

“The hot and humid climate in India, which deteriorates DNA over time, has made it difficult to obtain quality DNA material from ancient human residues,” the professor said.

Limited investment in genetic research compared to Western countries, has contributed to this shortfall in data, Mutharasan said. “The government needs to be more proactive in commissioning such research,” he said, adding that several ancient genomes – those of the first people inhabiting the region – are currently preserved at Egmore museum in Chennai. However, they haven’t been approved for analysis yet.

The lecture, deeply entrenched in science, ended on a more philosophical note—the idea of purity.

“People in India are a blended population and claims of purity do not stand true. One maybe more of one and less of another, but never just one,” he said. More DNA samples of the ancient genome are needed to get a complete understanding of South Asian genetics.

“Because what is true today, might not be true tomorrow.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)