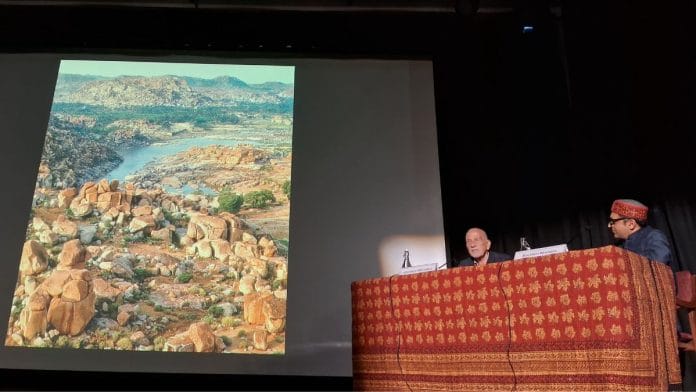

New Delhi: In Hampi, the stories of gods, temples, and land are intertwined. Australian author and architectural historian George Michell discovered the symmetries of storytelling when he studied the temple town in Karnataka for nearly ten years.

“Hampi may be in ruins, but the Ramayana, crowns, flowers… Rama, Lakshmana, Sita—these associations which were alive in Vijayanagara times are still very much alive today,” said Michelle, an authority on South Asian architecture.

His lecture—organised by the American Institute of Indian Studies at the CD Deshmukh Auditorium at Delhi’s India International Centre on 2 December—focused on his collaboration with John Fritz, the first American archeologist to survey the ruins of Hampi.

As an architect, Michell was drawn to the symmetry and geometry of the temple builders. At Karnataka’s Hazara Rama (a thousand Rama) temple, for instance, the south side of the antechamber walls depicts Ram giving his ring to Hanuman. At the exact same spot on the north side is a carving of Sita giving her hair jewel to Hanuman. Both these carvings are on a straight axis, which balance the symmetries of storytelling through the temple’s layout, said Michell.

While working together, Michell and Fritz observed a similar symmetry between the temple’s sanctuary, and the summit of Matanga Hill in the north. What caught their attention was a ‘third axial relationship’ between the Hazara Rama temple and the Malyavanta Hill, which is on the same “mythological route that Ram took” before marching toward Lanka to fight Ravana.

Such relationships between land and temple, imagery and religion make Hampi a fascinating study, said Michell.

Indo-Islamic architecture

At one point during the lecture, Michell pointed to a slide of Hampi’s iconic Elephant Stables that was part of his presentation. “It’s an assemblage of tomb changers,” he said.

The Indo-Islamic designs found on the monuments caught the attention of the team of Michell and Fritz.

Vijayanagara was among the wealthiest empires during the 15th and 16th centuries, and was frequently at war with the Sultanate kingdoms. But there was also an exchange of knowledge, and the Elephant Stables stands testament to this. Each of its 11 stables has a circular dome, resembling those found in Mughal mausoleums such as Humayun’s Tomb or the Taj Mahal.

Later, an audience member asked Michell if “Muslims actually built anything in Hampi”. “It seems that a Muslim cavalry officer, one Amhed Khan, in the army of King Devaraya II, built a dharmashala in Hampi which also functioned as a place of justice, and of law. Though it looks like a mandapa, it actually functioned as a mosque,” said the author.

Similarly, the Queen’s Bath of Hampi, also known as the ‘pleasure pavilion’, has several arched windows ornamented with plaster, along with domed ceilings that are unique to Indo-Islamic architecture.

“This has nothing to do with South Indian architectural tradition, but everything to do with the Deccan Sultanate tradition,” said Michell. And some habits like voyeurism and male gaze cut across cultures and the passage of time. The men would lounge in the balconies to catch a glimpse of women in the Queen’s Bath. Michell even took a dig at Bollywood.

“And it suggested to me one of the constant scenes that you have in Indian movies—the wet sari routine,” he said, as the audience snickered. “I think it is the wet sari routine of the Vijayanagara male audience.”

Also read: John Lennon wrote a song full of expletives called ‘Maharishi’. Then he had to tone it down

Layout and zones of Hampi

With its granite boulders in various hues of pink, grey, and ochre, and the Tungabhadra river flowing through it, Hampi appears to be built in response to its landscape.

Michell devoted part of the lecture to looking at the various ‘zones’ in the city, each with a specific function. The residential zones are close to the urban core toward the south of the city. The sacred centre, in the north side, is characterised by sacred structures such as the Vitthala and Virupaksha temples.

The Royal Center housed the members of the royal family and administrative buildings like the Lotus Mahal. Other ceremonial structures like the Elephant Stables were designed to symbolise the king’s power and wealth. But it also depicts a deeper symbolic connection between the king and the divine, said Michell.

The 15th-century Hazara Rama temple built by king Devaraya II using granite is situated in the Royal Center and symbolises the union of the king and the god. Processions of important festivals like Maha Navami or Dussehra took place outside the temple for public view, but the outer walls had no depiction of Ram or the Ramayana.

On the other hand, the inner walls of the temple had carvings of Ramayana which were contained within the king’s world with limited access to the public. It was as if the king was making a statement, that the ceremonies that went with his power would be on the outside of the temple, but he wanted to contain Ram within his royal world, said Michell.

There was a sense of loss toward the end of the lecture as if the audience was mourning the destruction of Hampi itself. The city was abandoned after the 1565 Battle of Talikota when the Vijayanagara Empire fell to the Deccan sultans of Bijapur, Bidar, Golconda and Ahmednagar.

“Why was Vijayanagara never resettled?” asked an audience member. According to Michell, what was left of the Vijayanagar court after the death of the emperor Rama Raya, went south toward present day Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, where the dynasty “refounded itself.”

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)