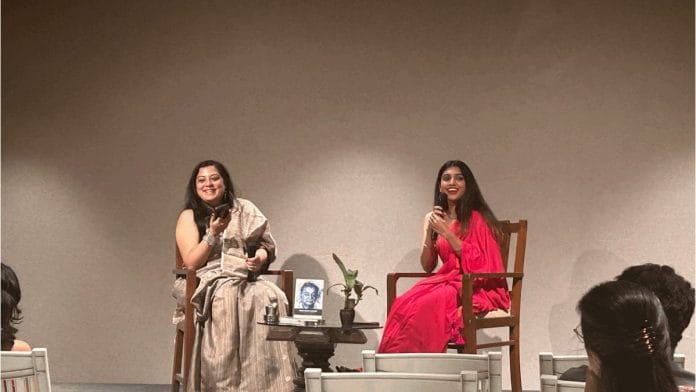

Bengaluru: Reams have been written about Dr Verghese Kurien who revolutionised India’s dairy production through farmer cooperatives and ushered the ‘White Revolution’. “Why read about Kurien now?” asked Kerala-based author and researcher MS Meenakshi at the launch of her biography on the Milkman of India last month at Bengaluru’s Atta Galatta bookstore.

This was also one of the biggest challenges she faced while writing Verghese Kurien: The Man Who Brought Milk to a Million Homes—how to position it differently from all the existing literature about him. She wanted to tell the stories of his leadership and the revolution he led through vignettes, unlike the pre-existing largely academic material on him. The biography is a slice of life, a peek into the engineer from Kerala who wanted to eliminate the middleman.

“Isn’t it funny how we humans often end up in jobs we don’t particularly enjoy? But Kurien flipped that script entirely,” said Meenakshi, in conversation with COO and director of Niyogi Books, Trisha De Niyogi.

Meenakshi’s literary debut was a biography of Kunjukutti Thampuratti, a social reformer from Kodungallur, Kerala. Now, she wants to inspire a generation unfamiliar with Kurien’s achievements to persevere and dream big.

Also read: Rise of veganism has been hard in vegetarian-friendly India. Milk is the final frontier

A story through anecdotes

Kurien was posted to Anand in Gujarat as a young dairy engineer in 1949. “It was Friday, the 13th.” He knew nothing of milk production and did not drink it either.

“He completely disliked the job and wanted to leave as soon as possible. But he still put his 100 per cent into it and ended up transforming India from a milk-deficient country to the world’s largest producer,” said Meenakshi.

Everything about the quaint little village of Anand felt unknown and strange to Kurien, a Malayali Christian from Kozhikode. Bullock carts would wait to pick him up, most people were vegetarians, and they spoke Hindi and Gujarati. And Kurien was put up in an untended, dingy garage owned by the research creamery’s superintendent.

“Everyone looked at this foreigner suspiciously…they were reluctant to give him proper accommodation,” said Meenakshi narrating an anecdote from her biography.

“But it didn’t deter him…he made a temporary bathroom by partitioning the room with a piece of canvas. He burrowed a hole and made windows on the wall. He threw some mud into the grease pit and levelled the ground. Kurien was all ablaze.”

His vision to empower small and marginal farmers and landless labourers motivated him. He never sat idle even on weekends.

“He would go to the field and work with farmers. Then he would go to factories and see if restrooms were in a proper condition for women,” said Meenakshi, who works as a UX writer for a fin-tech company in Bengaluru. She collected such deeply personal details of Kurien’s life over a period of two years.

Through such anecdotes, Meenakshi, chronicles his return to India after studying mechanical engineering in the United States to his relentless pursuit that transformed Amul into a household name.

“Whoever came in the way of this vision, Kurien taught them a lesson,” she said. In 1956, Kurien went to the Nestle headquarters in Switzerland with a mission to convince the company to manufacture condensed milk in India from Indian milk instead of importing milk powder and sugar. But things took an ugly turn when Kreeber, a co-MD of Nestle Alimentana said that the process of making condensed milk was extremely delicate and could not be left to “natives”.

“Kurien felt extremely disrespected…but he used this as a motivating factor,” Meenakshi said.

Even though every scientist from the West told him it was impossible to convert buffalo milk—which Indian farmers were heavily reliant on—into milk powder, Kurien with his friend HM Dalaya, a dairy engineer, achieved this feat two years after he stormed out of the Nestle meeting.

Eventually, when Nestle’s Kreeber came to do business with farmers of Anand, Kurien asked him, “So, Mr Kreeber, what do you think of the natives now?”

Also read: Did Harappans exploit animals for dairy? Lipid residue from Gujarat’s Kotada Bhadli has answers

Averse to politics

A large part of the book is dedicated to Kurien’s complicated relationships with political leaders including former prime ministers Lal Bahadur Shastri and Jawaharlal Nehru, and then Chief Minister of Gujarat Jivraj Mehta.

For example, although Shastri urged Kurien to replicate the Anand model of dairy cooperatives nationwide, his government was unwilling to fund such a Herculean task, forcing Kurien to approach the World Bank for help.

“He faced a lot of such problems with bureaucracy…that made him averse to the idea of ever becoming a babu,” Meenakshi said.

When Shastri wanted Kurien to be the chairman of the newly formed National Dairy Development Board (NDDB)— now a leading organisation in the dairy sector in India—the latter retorted with a condition: that he wanted NDDB’s headquarters to be in Anand instead of Delhi to avoid becoming enmeshed in political wrangles. “This way,” Meenakshi said, “Kurien remained a man of the poor farmers.”

At the same time, he was a savvy marketeer. He supported the Amul Girl advertisement campaign, which often caricatures current events to remain relevant. It’s one of the longest-running campaigns in India—and it hasn’t shied away from making political statements.

“When Kurien was alive, he would urge the marketing team not to hold back from saying anything,” Meenakshi said.

He had a similar view on competition—the more the better. During the audience interaction, a gentleman spoke about how his friends, who own cafeterias, have shifted from Amul to Nandini Milk, owned by the Karnataka Dairy Development Corporation.

“Amul, a legacy player, is now facing increasing competition from brands like Nandini,” said the audience member, following it up with whether it was because of Kurien’s absence. He died in September 2012. But according to Meenakshi, Kurien was never opposed to competition. “Especially because this race is, in the end, uplifting farmers and the rural community,” she said, crediting Nandini’s success to Kurien’s model of dairy cooperatives.

At one point in the conversation, Niyogi wished Kurien was alive today, especially “at a time when farmers continue to be exploited.”

While the audience nodded in agreement, Meenakshi didn’t quite agree with this. He would have been proud of the strides made by Amul, she said, pointing out that the cooperative launched 33 new products during the pandemic, at a time when major industries faced losses. “They found loopholes within the market that uplifted the rural community…for example, selling packaged items that were in demand during lockdown period and introducing products like immunity boosting milk in variants of turmeric, ginger and tulsi and Indian sweets like barfi, kaju katli and laddoo,” Meenakshi said.

“These efforts helped generate Rs 800 crores for farmers.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Showed us around the facility in 1973. Very disdainful of mandarins.