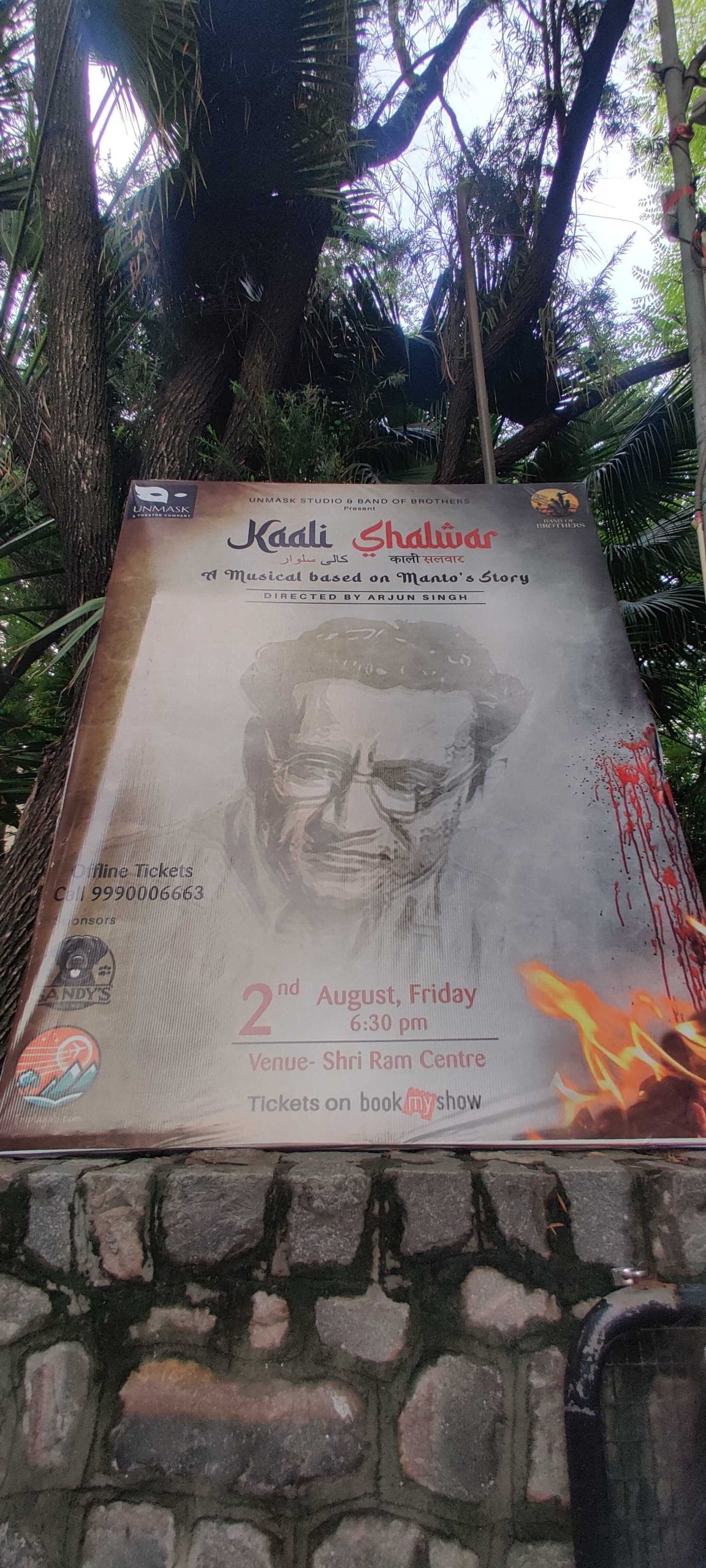

New Delhi: As the lights dimmed in New Delhi’s Shri Ram Centre for Performing Arts, a couple from Mumbai, who had spent their youth watching countless plays, settled in for what they anticipated to be an evening of nostalgia.

However, midway through the performance, the husband murmured through the audience, “Yeh kya ashleelta hai? (What is this obscenity?)” As the audience gasped at an intimate scene, it became clear that one thing definitely hasn’t changed—Saadat Hasan Manto still manages to offend people.

“Zamaane ke jis daur se hum iss waqt guzar rahe hain, agar aap isse naawaaqif hain, to mere afsaane paḍhiye. Agar aap in afsaanon ko bardaasht nahi kar sakte, to iska matlab hai ki ye zamaana naaqaabil-e-bardaasht hai (The era we are living through at this time—if you are unaware of it, read my stories. If you cannot bear these stories, it means this era is unbearable).”

Standing in a white kurta, round glasses perched on his nose, a cigarette in one hand, and a notebook in the other, Arjun Singh, who portrayed Manto, took centre stage in the opening scene. He introduced himself with one of Manto’s poignant quotes about why the literary icon wrote his “afsaane” (stories)—“If I don’t write stories, I feel as though I haven’t dressed, bathed, or had a drink.”

Unfiltered and unflinching

Manto’s stories were renowned for their unfiltered and unflinching portrayal of society’s darker sides. Often set against the backdrop of a tumultuous socio-political climate, they delved into the themes of Partition, poverty, and the human condition with a rawness that challenged societal norms. Kali Salwaar (1941) is one of them.

After two months of intensive reading and writing, Singh teamed up with actor Tushar Gupta and musician Abhay Tyagi in Mumbai. Together, they assembled a group of actors in Delhi and Mumbai to bring Manto’s writing to the stage.

Kali Salwaar follows Sultana (Isha Sharma), a sex worker who desires a black salwar for Muharram. She moves to Delhi with Khudabaksh (Gopal Satyamitra), a truck driver with a troubled past. In the city, she meets Shankar (Gupta), who promises to get her the salwar. When she finally receives it, she discovers that it belongs to her friend Mukhtar (Vishakha Srivastava), another sex worker. She also notices her own missing pair of earrings—which she had given to Shankar—on Mukhtar’s ears.

In the short story, Manto empathetically portrays the lives of sex workers, highlighting their dreams, vulnerabilities, and the harsh realities they face. While directing the play, Singh introduced two new perspectives: consent and devotional love. According to him, the beauty of Manto’s writing is that it offers “different perspectives”.

Also read: This play is all about a hospital waiting room—5 actors, no plot and a damp basement

Ghazals for love and heartbreak

The 1-hour-and-20-minute-long play seamlessly blended music and narration, earning a separate standing ovation for its live classical melodies. The ghazals of Begum Akhtar, the “Mallika-e-Ghazal”, enriched key moments of the story. Hamari Atariya Pe Aao played during Sultana and Shankar’s first meeting while Ae Mohabbat Tere Anjaam Pe Rona Aaya accompanied vulnerable moments between the two.

In the play, as Sultana waits all night for Shankar, a haunting verse conveys her longing: “Kaaga re kaaga re mori itni araj tose, chun chun khaiyo maans.” The speaker in the song pleads with a crow to eat all their flesh but not the eyes, so they may gaze upon their beloved once again.

When Shankar finally arrives, dishevelled and with buttons undone, he silently hands over the black salwar to Sultana. Sanson Ki Mala begins to play and continues through the final scene where Sultana, dressed in black, confronts Mukhtar, also in black but with a white salwar and wearing Sultana’s earrings. This moment of realisation captures their shared devotion and heartbreak caused by the man they both loved.

“The song symbolises devotion in love,” Singh told ThePrint. “When Shankar and Sultana hug each other, we can associate them with Radha and Shyam. Many might question this and argue that this challenges religious beliefs. But the essence of what is happening is beyond religion; it’s about understanding love and devotion in all its forms.”

Sultana in the play appears in a blouse with visible cleavage and a long skirt, setting the tone for a raw and honest depiction. Intimacy between the characters is portrayed symbolically, using gestures like the lotus mudra, which highlights emotional and spiritual connection.

“It’s not just an intimate scene, but a reflection of Manto’s truthfulness in his writing. We were clear—if we’re showing intimacy, we’ll go all guns blazing,” said Gupta.

Also read: If you’re watching this now, I’m already in jail. New Umar Khalid film blames media, BJP

Conveying Manto’s ideology

Singh also added a scene in the script that isn’t present in the original story to emphasise the theme of consent, which is often overlooked in the context of sex workers. In this scene, a customer rapes Sultana, which echoes Manto’s provocative question, “Kya fark hai Sultana aur dusri aurton mein? (What is the difference between Sultana and other women?)”

Singh explained that the scene was meant to provoke discomfort and reflection. “Many audience members have told me it gave them goosebumps, and that’s what I aimed for.”

Every now and then, after his multiple appearances as Manto during the play, Singh would sit in the front seat among the audience, watching the story unfold both as Manto and as himself—the director.

“The whole idea was to convey Manto’s ideology—what he used to say, what he stood for—and that was very important to me,” Singh said. “Rather than focusing on his body language, I wanted to present a soul in front of you.”

Manto’s works were revolutionary for their candid exploration of taboo subjects. Deeply affected by Partition himself, the Urdu writer moved to Pakistan, where he captured the human side of this upheaval in stories like Khol Do (1948), Thanda Gosht (1950), and Upar Neeche Aur Darmiyaan (1989).

“Manto has always seen women as women first. He was not one to sugarcoat his words; he portrayed things exactly as they were. That’s what sets him apart from other Partition writers,” said Vaishali, an audience member and a big fan of Manto’s stories.

Manto’s stories mirrored the flaws of the society in which he lived, which is the reason for their continued relevance in contemporary discourse. As the curtain fell, Singh repeated the writer’s powerful words: “Who am I to strip society bare when it is already exposed? I don’t try to cover it up—that’s the job of those who create the garments.”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

It’s just North Indians who obsess over Manto. Manto is lucky in this sense. Had he written in any of the four main South Indian languages (Tamil, Telegu, Kannada, Malayalam) or even Bengali/Marathi, he would have been considered a second rate author. Nothing more than that.

The acute paucity of high quality literature in North Indian languages has helped him attain this stature. The Print, obsessed as it is with north India, naturally sings paeans to him.