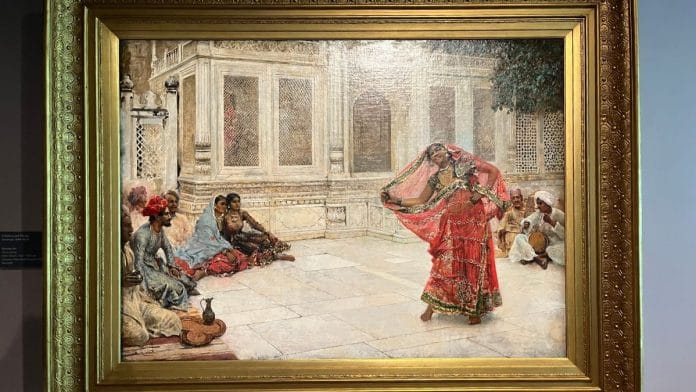

New Delhi: There’s a lot going on in American artist Edwin Lord Weeks’ Dancing Girl. She is in motion, and there’s an almost overwhelming range of expressions visible on the faces of those who are watching her—including a lurker visible through the jali. It looks like a faithful representation of a Rajput court. Except, there’s a catch. The architecture is Mughal, and the girl has been placed where she doesn’t belong.

“Everything about what’s happening is fantasy. It’s been constructed for Western consumption. These are layers we have to peel away,” said Giles Tillotson, curator of the exhibition and senior vice president, Exhibitions, DAG.

Destination India: Foreign Artists in India 1857-1947, on display at the Janpath-based gallery till 24 August, combines the work of a number of orientalist artists who immersed themselves in India in varying degrees. There are the usual fixations, such as the Taj Mahal and the ghats of Benaras, and also those who devoted themselves to the cityscape—depicting life as it unfolded on colonial-era streets.

There’s a specific gaze that accompanied these artists, a fascination laced with condescension. At a curatorial walk last week, Tillotson laid out the facts: “They exoticise, they mysticise, they romanticise.”

The challenge, according to him, then becomes moving beyond “the mist of orientalism”.

Weeks was one of the first American artists to visit India in the late 19th century. Tillotson referred to him as their “rockstar”—owing to his sharp, very discernible brush strokes, which received compliments from Indian artist Jatin Das. “And he’s not one to ordinarily like this kind of art,” Tillotson said.

While it’s easy to view the artists in question as a monolith, the purview of their work expanded as time progressed. The ‘original’ orientalist artists who visited as guests of the British empire following the revolt of 1857—William Simpson, William Hodges, and Thomas Daniell—maintained a more moony-eyed, traditionally colonial disposition. There were also those with different styles and repertoire.

The British landscape artist, Daniell, kept a journal while painting. His writing suggests that he was annoyed by the presence of pilgrims as he painted the ghats. “In the paintings, they disappear,” said Tillotson.

The final product attests to this. The ghats are picturesque and dream-like, but there is not a soul to be seen, making it a fictionalised rendering of Benaras.

Also read: Art meets Ayodhya. NGMA, Lalit Kala Akademi are remaking India’s culture scene

Beyond the British

Orientalist artists are typically perceived as only being British. However, there were an array of nationalities which wound up in India. Dutch painter Marius Bauer, Italy’s Olinto Ghilardi, and Japanese printmaker Yoshida Hiroshi, among others.

While mining DAG’s collection, the curators themselves were surprised by the sheer number of non-British artists, and how little traction they received in comparison to their British counterparts. According to Tillotson, there’s an entire chapter that hasn’t been documented—Europe’s artistic engagement with India is a story in and of itself.

“One of the things I do in my job at DAG is that when I’m thinking about an idea for an exhibition, I go down to where the collection is stored,” Tillotson said. That’s when he noticed works by an artist called Marius Bauer. “I had never heard of him before.”

Bauer travelled to India twice—first in 1898 and then in 1924. He described India as “a wonderland of palaces and temples, populated with endless rows of brightly clad Orientals, of richly dressed carriages, of camels and herds of elephants.”

He went on: “The memory softens the shadows and the light, casts a transparent veil of reality and turns it into a dream image.”

One of his pieces—titled ‘Hindoos bathing at Benaras’—done on paper, is brimming with activity. The architecture is visible in all its glory, and there’s a cacophony of people—all of whom appear to be engaged in different activities. The buzz is seemingly an accurate representation of the city, but Bauer’s statement attests to what orientalist artists did, which was augment, embellish, or when it suited them — often prune reality.

While India embedded itself as a major source of inspiration for European artists, with orientalist art retaining popular appeal in Britain and other countries to date—the transference has been one-sided. Their ideas and ways of working made their way into Indian schools of art, such as the Sir JJ School of Art in Mumbai, but they never touched Indian art.

“The transmission is all one way. These artists, they’re responding to life and people, but not so much to their art,” said Tillotson.

There are limitations even in how orientalist art has been perceived in Britain. Lure of the East: British Oriental Artists, a 2008 exhibition at the Tate in London had no mention of India.

“The East in question ended at Damascus,” Tillotson said.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)