New Delhi: The romance of Old Delhi—of cavernous havelis, spontaneous mehfils, and a shared faith in the spirit of Dilli is intact in stereotype only. Otherwise, it’s coming to an unceremonious end due to an absence of civic amenities, and a citizenry that prefers to live elsewhere.

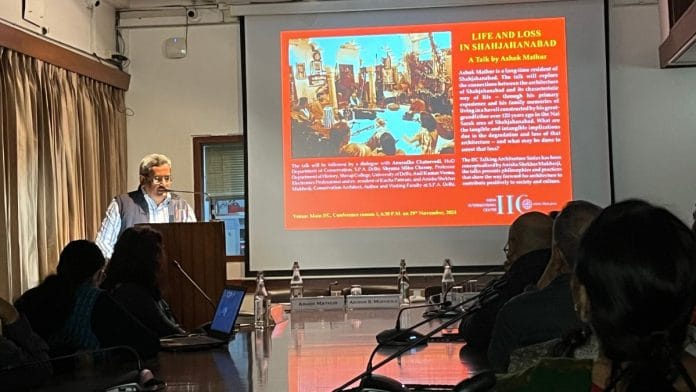

A discussion at the India International Centre was an ode to a bygone era and a friendlier city. Ashok Mathur, a long-time Shahjahanabad resident, opened doors to life in an Old Delhi haveli. The panel also consisted of conservation architect Anisha Shekhar Mukherji and Shama Mitra Chenoy, professor at the University of Delhi. The lecture was part of a series on the ways in which architecture enriches society, and how to treat architecture as an ecological and social driver.

“We find the idea of living in Shahjahanabad difficult to grasp today. But he (Mathur) continues to live there against all odds,” said Mukherji, while introducing Mathur.

There were baithaks in which harmonium was played, a gathering that often turned into a spontaneous concert. Mathur would count stars as he slept on his terrace on balmy summer nights. There were at least 20 Jain temples—constructed from the time of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan till Bahadur Shah Zafar. Effigies of Holika were burnt in Muslim-majority areas.

“Our ancestors had created a beautiful world, and the mannerisms and culture remain dear to me,” said Mathur. “The city had a huge influence on my personality and thinking. I’ve seen its decline, the loss of architectural glory and its tehzeeb to which I stand a silent witness.”

He further described his historical quarters as “a ghetto”, a sad fate supposedly accorded to a city that was once a “great exemplar of community living.”

To describe the spaces in his home, Mathur used words that have been lost to changing times. ‘Jhot’—a small space between the kitchen and the outdoors in which trash was thrown. A ‘palendi’—the shelf in the kitchen on which utensils were used.

“Our architectural vocabulary is shrinking, and therefore the diversity of our architecture is also shrinking,” said Mukherji.

Also read: Ghazni’s Somnath Temple loot is absent in Sanskrit texts. House of Commons started the debate

‘Complete mismanagement’

Anil Varma, a former Old Delhi resident present at IIC, said that he was “haunted” by his memories of life in the old city. However, as time passed, he made peace with them and now recalls the sounds of the chai wallah who always had his radio on, the dharamshala which was always hosting a wedding, with fondness.

“I live in South Delhi, but my heart’s in Old Delhi,” Varma said, before launching into an imitation of a vendor who used to cross his street daily.

The romance of the city is alive. However, upon being asked whether or not they’d like to live in Shahjahanabad, there weren’t too many takers. Golf Links had more. This seemingly innocuous question is a glimpse into the nature of Delhi’s urbanity—divided and unequal.

“The city has slipped out of our hands. There is complete mismanagement,” said Mathur. The ‘Mathurs’—part of the Kayasthas, a service caste—used to occupy a hundred havelis, now only three occupants remain.

Veteran architect Ashok Lal was in the audience, and he attributed the now irrevocable change in the city to the influx of trade. The first demographic change came with Partition, and the second came with the railway station. Delhi became a warehousing city.

“You can see it so strongly. The motor parts market, the agriculture market, the spare parts market. This took over the entire fabric,” Lal said. “Families that are staying back are doing so out of no other choice. The economics of property and trade are determining what’s happening to the city.”

According to Mathur, Shahjahanabad is plagued by illegal construction, the real estate mafia, and most recently, the rush for groundwater.

“There needs to be a complete stoppage of illegal construction. Leave our city to us, and we will take care of it,” he said.

Laments were many, but solutions were few and far between. A lone, possibly ambitious, ray of hope—Master Plan for Delhi-2041. The plan includes context-specific building bye-laws, thereby taking account of history, heritage, and, of course, romance.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)