How would a Jawaharlal Nehru and Donald Trump meet in 2025 look like? Nehru would be calm and composed but they wouldn’t get along, said Italian author and associate professor Andrea Benvenuti.

The audience at Delhi’s Jawahar Bhawar laughed out loud. Most nodded their heads in agreement. Nehru, who was known to be a “fantastic” listener, would have kept his cool because he would most likely not consider Trump a ‘political icon’.

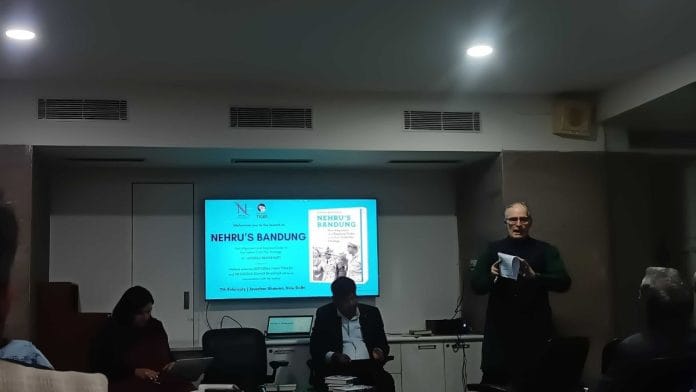

“Nothing really compares to Trump in terms of directness. And it’s almost like an elephant in a china shop. Nehru was a great listener, although sometimes he used to blow the fuse. But it would be a challenge,” said Benvenuti at a discussion based on his book Nehru’s Bandung: Non-Alignment and Regional Order in Indian Cold War Strategy last month. It was part of a lecture series, ‘Nehru Dialogues’.

Benvenuti was discussing Nehru’s foreign policy and the “Bandung Generation”—the leaders of former European colonies in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia who met in April 1955 in Bandung, Indonesia. The leaders wanted to establish a non-aligned movement during the Cold War, amid the rivalry between the US and Soviet Union.

Benvenuti’s book looks at Nehru’s views on Bandung using archival resources that draw from Badruddin Tyabji’s —India’s ambassador to Jakarta from 1954 to 1956— views on the alliance.

While Tyabji was dismissive about it and labelled the alliance “ a landmark of missed opportunities”, Benvenuti is not as snide. However, he does write in his book that “it failed to bring any Afro-Asian solidarity”.

Benvenuti is not concerned with Bandung as a whole but with Nehru’s vision of Indian foreign policy, particularly his role in the Bandung Conference.

At the panel discussion, which had political scientists Rityusha Mani Tiwary and Deepak Kumar Bhaskar, Benvenuti said that the sole purpose of writing the book was to look at “India as a stakeholder in the regional system, as well as a country with some agency”.

“Bandung was Nehru’s grand design and grand strategy for dealing with the Cold War in Asia,” he said.

Nehru, and global politics

As an associate professor in politics and international relations at the University of New South Wales, Benvenuti’s area of interest is international and Cold War history. And his lecture, like his book, was a deep dive into India’s role during the Cold War.

On 15 October 1954, Nehru embarked on a significant trip to China, aiming to strengthen India’s ties with its neighbour “in a very cheerful mood” despite a slight illness. His visit, marked by high-level send-offs and a warm reception in Beijing, was seen as an effort to assess China’s commitment to peaceful coexistence and regional stability. The Times of India described it as a mission for peace, highlighting the ideological differences between democratic India and communist China.

But as Benvenuti pointed out, Nehru was wrong. China was not a friend.

The author noted that China remained dedicated to revolutionary change both domestically and internationally. It suppressed dissent in Tibet, launched the disastrous Great Leap Forward that caused millions of deaths, and in 1962, attacked India over territorial disputes near the McMahon Line and in Aksai Chin. For Nehru, the 1962 border war was a significant foreign policy failure, Benvenuti said. The border dispute was never resolved, and India has since aligned more closely with the US in its rivalry with China, effectively reversing Nehru’s foreign policy.

“In his quest for a more stable regional system, the Indian leader (Nehru) had long argued in favour of engaging with China. According to him, there could be no enduring stability if China remained an outcast on the fringes of the international system,” Benvenuti writes in his book.

Also read: Wim Wenders is buying the rights to all his films. ‘Storytelling is now storyselling’

Afro-Asian solidarity and more

Rityusha Mani Tiwary argued that Nehru’s involvement in the conference was part of a broader strategy to secure regional stability and counter external pressures, particularly from Western powers. Nehru, she suggested, was motivated by a desire to chart a course independent of both the US and the Soviet Union, and the Bandung Conference was a key step in this direction.

The conference was not only a diplomatic triumph but also a moment of ideological experimentation. As Deepak Kumar Bhaskar pointed out, Nehru’s strategy was a counter to the prevailing militaristic rhetoric of the Cold War.

“Bandung foreshadowed the awakening of Africa and the arrival of Asia on the international stage,” Benvenuti writes.

Nehru’s vision of peaceful coexistence and non-alignment provides a timeless blueprint for navigating the evolving dynamics of international relations. According to Benvenuti, the Bandung Conference, an Afro-Asian gathering that brought together newly independent nations, was a momentous event in global diplomacy. It offered a platform for countries seeking to assert their autonomy outside the polarised blocs of the US and the Soviet Union. Nehru’s involvement was a carefully calculated move to assert India’s place as a leader of the so-called “Third World”, the author said.

“His vision for peaceful coexistence, rooted in non-alignment, sought to carve out a space for emerging nations to navigate a world defined by superpower rivalry,” Benvenuti said.

Tayabji had referred to it as a “major diplomatic investment”. He said it was “a landmark of missed opportunities,” suggesting that despite India’s considerable investment in the event, the tangible benefits were limited.

This led Benvenuti to explore why Nehru decided to invest in it. He found that Nehru’s decision to support the Indonesian proposal for the Afro-Asian Conference was initially met with hesitation. However, as the political climate shifted, he realised that the event offered a valuable opportunity to position India as a mediator in the emerging global order. His backing of the conference was a move to counter dominant US policies and achieve a peaceful existence with China.

“If more countries adopted a non-aligned stance, Asia would become more peaceful, but also countries would not necessarily want to join blocs and therefore, in a sense, worsen the overall situation (post Cold War). Nehru’s advocacy for peaceful existence took the wind out of the sails of American containment in Asia,” Benvenuti said. But Nehru was wrong and he did realise his mistake later.

The historical context of the Cold War added another layer of complexity to Nehru’s decision. While the US and Soviet Union jockeyed for influence, India, along with other newly independent nations, sought to forge a neutral path—what became known as the Non-Aligned Movement.

Nehru’s vision of peaceful coexistence was deeply rooted in this philosophy, positioning India as a leader of nations seeking a third way outside the binary of Cold War politics. However, the differences between India’s approach and that of other nations in the Global South became evident as the years unfolded. China, for instance, emerged as a more radical voice, particularly after the rise of Mao Zedong’s leadership. Nehru, initially hopeful for a partnership with China, found that the ideological divide between the two nations could not be bridged, according to Benvenuti.

After that Asia never became the peaceful region Nehru envisioned, and China failed to become the responsible power he hoped for. As the book reveals, China exploited the Afro-Asian movement to promote its radical anti-imperialist agenda and undermine India’s influence. After Bandung, Nehru increasingly doubted the value of Afro-Asian solidarity in advancing India’s national interests, growing sceptical of the movement, as evidenced by declassified Indian documents.

“However, when it came to forging an enduring Chinese commitment to peaceful coexistence, Bandung and its legacy remain a testament to Nehru’s wishful thinking,” Benvenuti said.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)