New Delhi: When Narayani Basu started writing KM Panikkar’s biography, she intended to limit it to 200 pages. But as she dug deeper and deeper into Hindustan Times‘ first editor, and India’s first ambassador to China, she found Panikkar’s presence stamped across India’s modern history. The result was an 800-page authoritative tome, A Man For All Seasons: The Life Of K.M. Panikkar.

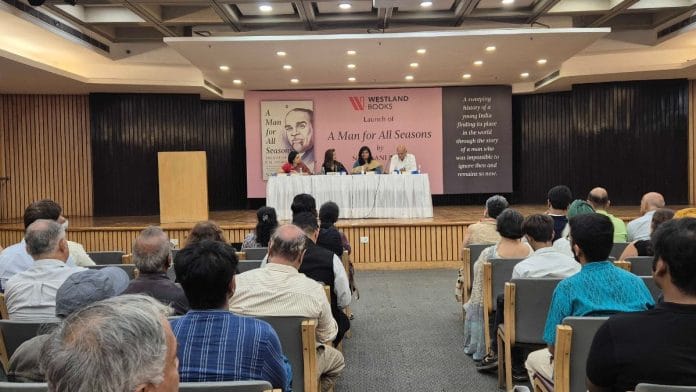

“Biographies not of the obvious persons (tall leaders) but those around them give us perspective on so much else that is not considered headline history,” said Karthika VK, the publisher at Westland Books, at the launch event at India International Centre, Monday. “We won’t have such a perspective without authors like Narayani who spend so much time documenting this history.”

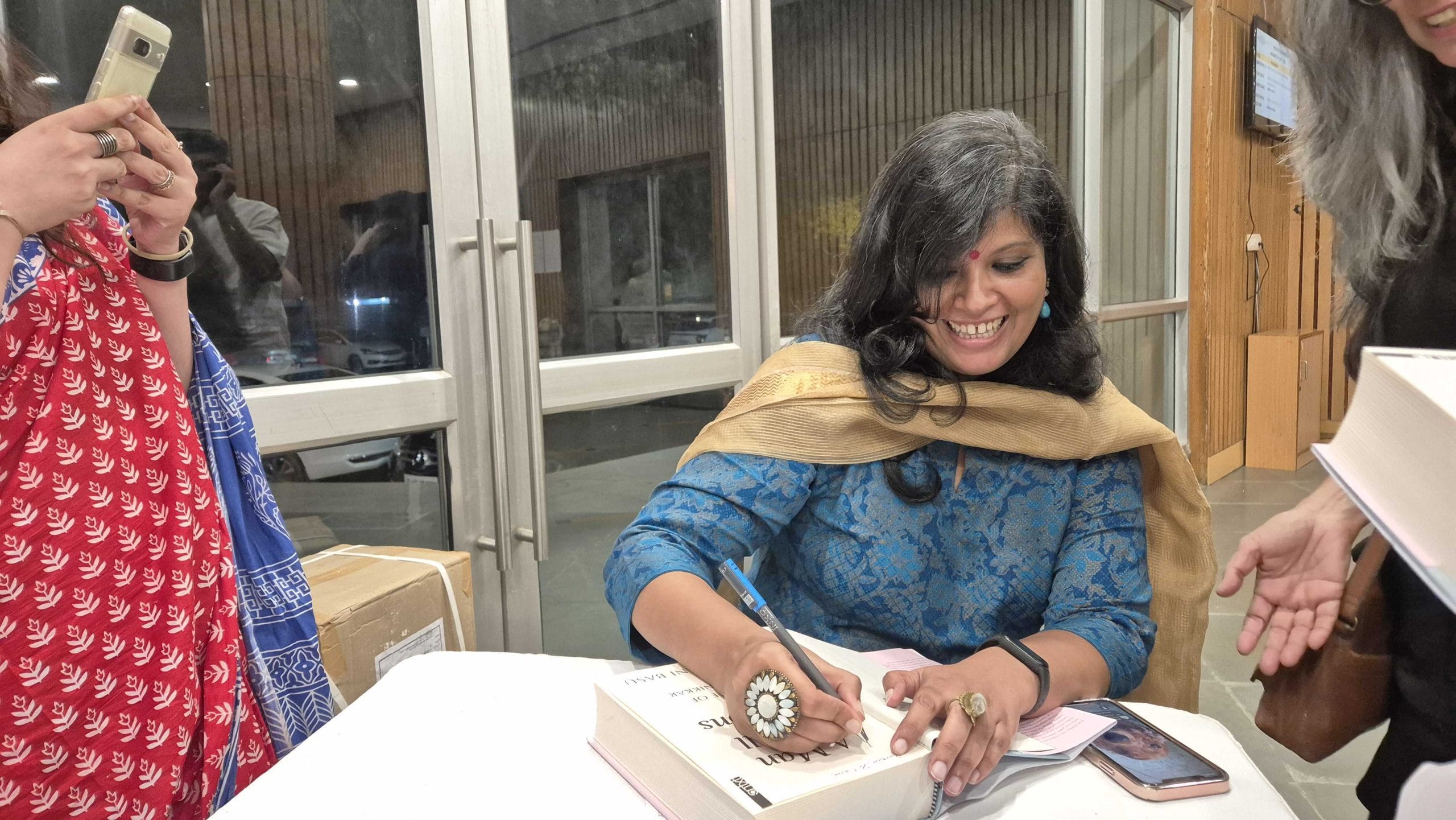

The book launch was followed by a panel discussion that included Basu, former ambassador Shivshankar Menon, and The Hindu‘s diplomatic editor Suhasini Haidar, moderated by journalist Pragya Tiwari.

A Man For All Seasons resurrects Panikkar—editor, diplomat, crisis manager, and “Hindu chauvinist” as Basu called him. He was the man Nehru trusted, but sometimes ignored; a nationalist of a brand not found in today’s politics, whose thoughts evolved with time.

“This was a man who was not just a diplomat, or an administrator in the princely states. He was a historian, a lawyer, a writer of fiction, a poet, one of the most ardent proponents of federalism… and these are things that just compartmentalise his career,” said Basu.

Panikkar wouldn’t have a social media profile—it was the verdict of the panellists. Constantly evolving thoughts are not favoured in the age of social media. “Thank God he didn’t have Twitter for people to post his old screenshots and yell ‘Hypocrite!’” moderator Pragya Tiwari quipped.

‘Pannikar was everywhere’

Historian Narayani Basu hit upon the idea of writing about Panikkar while working on the 2020 biography of the brilliant civil servant VP Menon. During her research, she repeatedly came across Panikkar, especially in connection with the Chamber of Princes, where he held the post of Secretary. Established in 1920, the institution comprised the rulers of the princely states of India and was dissolved after India’s independence.

Until then, Basu only knew of Panikkar as a controversial ambassador to China. He was accused of misleading Nehru about China’s military campaign in Tibet.

But Panikkar’s traces across history intrigued Basu, who started researching him, and said what she found in the archives “overwhelmed” her.

“Between 1915 to 1963, he was present for every milestone of India’s history,” she said, describing the canvas of his life as cinematic. His career milestones ran parallel to India’s historical milestones.

Panikkar returned from the University of Oxford to India right after World War I as a professor of history. His tenure coincided with the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, the passage of the Rowlatt Act, the Non-Cooperation Movement, and Chauri Chaura. As the first editor of Hindustan Times, he lent to the paper his perspective of where the country was going, his idea of nationalism.

Basu also emphasised that Panikkar was the pioneer of advocating for a maritime strategy to guard India’s seas. As Nehru’s man, he was also a nationalist.

“Panikkar’s life is an example that you need not necessarily fall on one side of a spectrum again and again. His nationalism was grounded in religion; Hinduism was the core of India’s identity, according to him. But he didn’t subscribe to a muscular form of Hinduism, for him, Hinduism is deeply inclusive,” Basu said.

Basu insisted that Panikkar was a chauvinist but not an outright sectarian.

Also read: Sheikh Mujib failed miserably despite succeeding as people’s leader, says author Manash Ghosh

A ‘scapegoat’

Panikkar is most infamously known as the man who misled Nehru on China’s Tibet policy. He was India’s first ambassador to China and severely underestimated China’s intention of military operations in the plateau, grossly misinforming Indian foreign policy.

Menon and Haidar argued that while Panikkar was wrong, he wasn’t the only one advising Nehru on China policy, but he was made into a scapegoat.

“I think it is much easier to blame an ambassador than the prime minister. He also wasn’t an institution builder, so there’s no institutional interest in defending Panikkar. He was still learning about China; he had no previous experience. Just being a historian is not enough, so he gets a bad rep for China,” Menon said.

When asked by an audience member why Panikkar didn’t enter politics, Menon gave a cheeky one-line answer: “Because he was a sensible man!”

Menon also said that Nehru had sought counsel from senior army officers about military operations in Tibet and was informed that India could send one or two battalions up the plateau for a maximum of a month, since India was already in conflict with Pakistan and was dealing with post-Partition internal strife and security issues.

According to Haidar, there was no winning for anyone deputed to China. For diplomats in China or Pakistan, it’s a lose-lose situation. But she said Panikkar did drink a lot of Chinese “Kool-Aid” at the same time, because Panikkar believed in Asian powers over the Western world.

“Just like diplomats face issues when it comes to Pakistan, so they do with China. Panikkar was able to get one-on-one dinner conversations with Chinese leadership that went against him. He was seen as a diplomat who went native,” said Haidar.

Panikkar’s role in going on the ground in Bikaner during Partition, when riots broke out along the Rajasthan border, was also spoken highly of. But not without an interjection from an audience member.

“Those who thought Partition was inevitable led to the suffering of millions,” said the audience member. Tiwari stepped in and requested that audience members stick to questions and save their remarks for later. There was an awkward and uncomfortable silence, one that Panikkar would have bridged with the ease of a diplomat.

In the end, Suhasini Haider reminded everyone of his role in shaping history.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)