Bengaluru: Bihar, which has been long known for its caste conflicts, was once a region where many Brahmin students studied under non-Brahmin and Dalit teachers in schools.

With this example, historian Parimala V Rao began her lecture on how indigenous education in India changed under British rule.

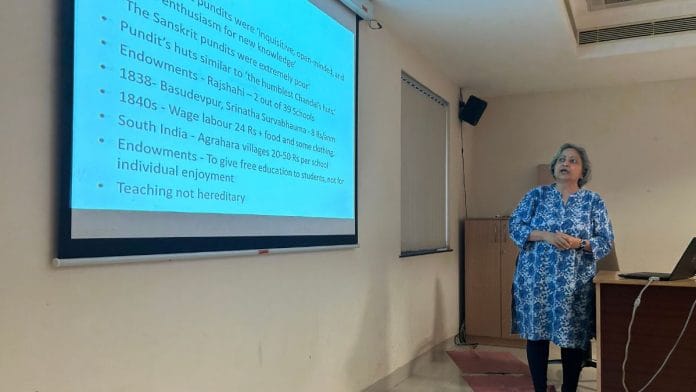

In her two-hour lecture at the National Institute of Advanced Studies in Bengaluru, Rao challenged the prevailing narrative that the British imposed English and modern education on Indians. Presenting rich archival evidence and data on 16,000 indigenous schools in British India, she asserted that education in traditional schools was not oral, informal, and Brahmin-centric—it was written, formal, and egalitarian. The colonial state, in fact, actively opposed the introduction of modern education through its policies.

“In the first hundred years of colonial rule, all the educational institutions established by the colonial state were Arabic and Sanskrit colleges and all the modern educational institutions were established by Indians. Yet theories have been built on how the colonial state imposed modern European knowledge over the colonised,” said Rao, who teaches History of Education at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), Delhi. She examined archives from the 18th and 19th centuries, which revealed a very different picture.

Inclusive classrooms

In 1819, Brahmin teacher Baji Pant Marathe would go to a small shed in his village Pent (in modern-day Chhattisgarh) to conduct daily classes. The shed belonged to a person from the Teli caste (considered a ‘lower’ caste). Sitting in this shed was a mix of students from different castes – six Sonars, one Shimpi, 10 Bhandari, 3 Mali and only one Brahmin, Parimala V Rao told the audience. “It didn’t matter which caste the student belonged to. The teacher would give everyone the same importance,” she said, referring to one of the several stories she collected from the Indian Office Records in the British Library in London.

Temples, sheds, mosques and houses of rich people transformed into Sanskrit and regional language pathshalas by the 19th century. These weren’t just basic schools, though. From translations of Ramayana, Mahabharata and Panchatantra in regional languages to arithmetic, long division, and classes on drawing out bills of exchange – indigenous schools covered everything, claimed Rao, referring to the report on indigenous education (1850-52) available at the National Archives, New Delhi. “Failure was unheard of in such schools,” she added.

Students were taught for over 12 hours in these schools, with a morning and afternoon break, said Rao on the basis of records and minutes left behind by colonial officers such as Thomas Best Jarvis, Thomas Munro and William Adam. These officers collected comprehensive data on indigenous schools between 1819 and 1853, which is available at the Institute of Education Archives in London and the National Archives in New Delhi.

Rao then explained different policies that the British introduced, which promoted education in regional languages while ensuring inclusivity. Under one such policy of the British administration, she said, officers were given seven years to learn Sanskrit/Arabic plus one modern Indian language mandatorily. If they failed to do so, they were sent back to England.

“It wasn’t just about learning basic classical and modern language. They were asked to translate one of Kalidasa’s English works to Sanskrit and vice-versa,” Rao said. The same policy was also in place for students until their matriculation.

The effectiveness of these initiatives was evident. Major General Sir William Reid noted in the report on indigenous education 1850-52 that boys joining indigenous high schools could master “cube root, four books of Euclid, and algebra up to division within a year and answer difficult questions with astonishing rapidity.”

Observing such benefits, the British also introduced a policy of incorporation by the 1840s, wherein a national educational system based on the foundation of indigenous schools could be established (as mentioned in the Report of the Indian Education Commission printed in 1883).

“The only reason we have all this information is because of British liberals. Officers like William Adam visited over 2,000 schools in Bengal Presidency, sat in the classrooms, and observed the method of teaching. They collected data on indigenous schools to urge the colonial government to spend on improving these schools,” Rao said, quoting from Adam’s reports on the state of education in India between 1835 and 1838.

What changed

If everything was so picture-perfect for indigenous schools under the British, what changed, an audience member asked Parimala V Rao. The question led the discussion toward the decline of such institutions in the mid-19th century, when the British crown took over the reins from the East India Company.

“While Dalits and other subaltern groups exhibited their intention to fulfil their intellectual craving for modern education by enrolling in it, their efforts were frustrated by the colonial state dominated by the British aristocracy, which argued that only the Brahmins and Muslim elites should be educated,” Rao said while quoting from reports on education after the 1900s, available at the National Archives in New Delhi.

The newly established Indian political leadership was virtually representing these feudal interests, Rao remarked. For example, Peary Mohan Mukherjee, an Indian member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, opposed a mass education bill that aimed to include lower castes, according to a collection of his writings and speeches published by Tarak Nath Mukerjea in 1924.

“He said education shouldn’t be given to lower class people as they will not respect the upper caste,” Rao told attendees. Soon after, there was a consistent drop in the number of lower-caste students who made it to high schools and universities, the professor said based on her analysis of reports on Indian education after the 1900s.

Moreover, the salaries of teachers remained stagnant, said Rao. The highest a teacher got paid was Rs 6-8 per month while an average daily wage labourer earned Rs 24 at the time, as per the India Office Records at the British Library in London. “Better teachers didn’t enter the system, only those who didn’t get the job anywhere else would end up becoming a teacher,” Rao said.

Some of the worst famines also hit British India in the second half of the 19th century. As a result, the colonial state spent large sums of money on famine defence and relief. There was hardly any money left to develop and maintain indigenous schools, the professor stressed.

Today, many of these pre-colonial indigenous schools have been developed into government-controlled primary educational institutions, said Rao, after observing the report on pathshalas by the General Committee of Public Instruction (the first education department in India). “While the names of these schools might have stayed the same over decades, caste conflicts within the larger society overpowered these institutions’ original inclusive form.”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

Even today we do the same in remote villages of India. Brahmin and sudra share food and drink water from same pot.