New Delhi: When it comes to Prakrit, linguist Peggy Mohan goes against the grain. It was not the language of the common people, she claims. It was more of an official language from the sixth century BC to the 12th century CE.

“Prakrit is almost identical to Sanskrit. There is a slight difference in pronunciation. The grammatical complexity is very similar in Prakrit and in Sanskrit, but there is just a little bit of local feeling,” Mohan said at the launch of her book, Father Tongue, Motherland: The Birth of Language in South Asia at Delhi’s Jawahar Bhawan on 19 February.

The launch offered the perfect segue into the evolution of language and how its usage has adapted to fit the local lexicon. The use of the word ‘only’ in Indian English, for instance, has become the subject of many memes and reels—‘This is with me only.’ But according to Mohan, Indians are not violating English grammar. That said, she admitted that the usage is strange because there is one word missing, and that is ‘have’—‘I have this thing.’

“What we said is not wrong, but it is strange. It is local, no rules have been broken, and that is similar to Prakrit,” said Mohan.

Just as English is spoken today in various regions with different accents, so was Prakrit, back in the day. People adapted the ancient language in the local flavour, resulting in different pronunciations.

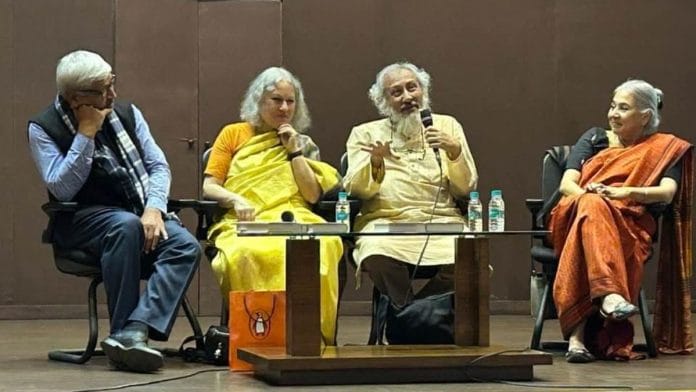

Mohan was joined by linguist Probal Dasgupta and historian Swapna Liddle, who discussed the story of the journeys of languages with moderator Apoorvanand.

Dasgupta said that people always talk about words, not about sounds. “But linguists spend most of their time dealing with those minute differences. The one that the public is not interested in.”

He added that words tend to disappear very quickly. The result is that words often create division and violence.

A question of power

Politics, the people in power, impact the contours and spread of a language. The Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal emperors were not interested in promoting Prakrit.

“But they were interested in other languages like Bengali, Marathi. That’s why the 12th century is when these languages came into importance,” said Mohan. And Prakrit was sidelined, no longer politically important.

Conversation flowed back and forth in time and history as the panellists immersed themselves in lost languages and the evolution of new ones. At one point, Mohan asked an intriguing question. How long did the old languages last and when was the last evidence of an Indus Valley language being spoken in the area that is now Pakistan?

“We don’t know,” she said. It could have been as recent as a thousand years ago. It’s almost as if the language vanished within generations, with the entry of new rulers.

Also read: Urdu daily ‘Pratap’ was shut in just 12 days of launch. It taught us real journalism

Father tongue, motherland

In Father Tongue, Motherland, Mohan explores how mixed languages came to exist in the Indian subcontinent. By default, children may be close to their mother tongue, but the movement of languages like Bengali, Marathi, and Hindi reflect the migration of men.

“Like a flame moving from wick to wick in early encounters between male settlers and locals skilled at learning languages, the language would start to go native as it spread. This produced ‘father tongues’ with words taken from the migrant men’s language, but grammars that preserved the earlier languages of the motherland,” she wrote in the book.

Mohan also talked about how she chose the title of the book—it was an idea that took root in her mind 50 years ago when she moved to India.

“I’m from the Caribbean region, where I looked at creole languages. In my mind, the question was what to make of the languages in India,” she said.

In her quest, she studied not just Hindi but Bengali and Marathi as well.

“I would say they are not alike. But the reason for them being different can’t just be that Sanskrit just changed overnight. That’s not the way things happened in the Caribbean and maybe it did not happen the same way here,” Mohan added.

What informed her research was the entry of geneticists tracing human migrations. It is also where she gets the title of the book, Father Tongue, Motherland.

“Men created the cohesion and the women created the bhoomi (land),” she said.

Also read: PILs have gone from social activism to Private Interest Litigation, says Justice Nagarathna

Vedic influx

In her book, Mohan traces the language of the Indus Valley Civilisation. The idea that the civilisation must have had a continuum of related dialects reflects the belief that in the process of building a civilisation, the group in power would have absorbed local communities and their languages, she said. “Some of them [the ruling class people] probably isolate languages unrelated to any of their neighbours.”

In the early period of Vedic influx into the subcontinent, most of the local people would have spoken languages and dialects linked to those of the Indus Valley groups, along with some unrelated minority languages.

According to Mohan, it is possible that local women were pulled into the Vedic community as wives. And some elite men from the Indus Valley Civilisation could have made the effort to learn the language of the Vedic group, Sanskrit.

“The first brackets [the first people to learn Sanskrit] come up this way. But if the daily lives of the little people were not too disturbed, they would probably have continued speaking their earlier languages for as long as their world remained stable,” she added.

During the audience interaction, the conversation again shifted to the weaponising and politicisation of language. How would you correlate the title of your book with our current contemporary history, an audience member asked.

Mohan chose to answer this by using the example of the prevalence of English in India.

“Right now, you and I are speaking English. Neither one of us owes our English to the British being here. We know it because it is a language of political power in this country, much more since Independence than before.”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

Lot of writing talking without saying what it is

Generally people says home land not mother land . In languages it is noted that ” mother tongue “, mother is first person teaches words in languages to children . Later on mother tongue developed into languages, literature and official status. What ever present people uses the language is valid and ancient languages are only basics for modern languages.

In the digital age all Indian languages are using English script like Hindi as Hindish or Telugu as Telugish …… so on forth . Mostly languages are learn with applications of English for script and accent or pronunciation.

Sign language also developed by technocrats in Bangalore to easy with local people. Throughness in one language is quite enough rather then learning the multiple languages in mess condition. For academic and employment purpose one language efficiency is quite enough and rest of the languages are ” CHALTHI KA NAAM GADI “