New Delhi: Amrita Sher-Gil has been called many things: a feminist before her time, a cosmopolitan who moved between Paris and Punjab, to the artist who made brown bodies visible with dignity and depth. Even Jawaharlal Nehru admired the Hungarian-Indian painter – a creative force who redefined the country’s modern art scene, and a restless spirit drawn to both sunlight and shadow.

Now, a new exhibition at New Delhi’s National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), on view till 30 April, casts her in another light—less as a legend, more as a link between Europe and India; between a nation’s cultural memory and a quieter story of shared histories.

In recent years, countries with smaller footprints on the global stage have begun leaning into art, archives, and shared heritage to strengthen ties with India. Amid this soft cultural churn, Amrita Sher-Gil emerges as a natural bridge. Born to a Sikh father and a Hungarian-Jewish mother, educated in Paris, and rooted in India, her life was a map of entangled worlds. She doesn’t just belong to India’s modern art history—she belongs to multiple stories at once.

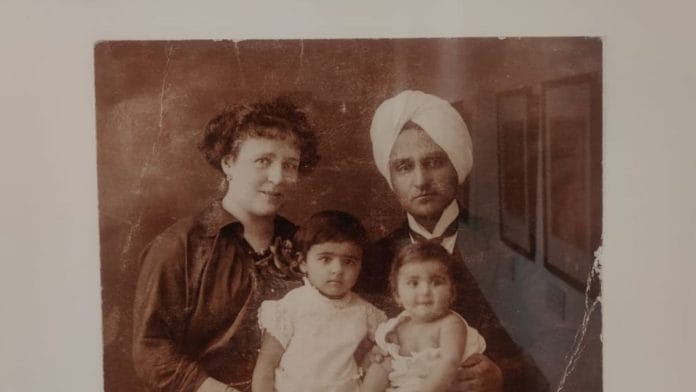

A Hungarian-Indian Family of Artists: Master and Disciple brings Amrita Sher-Gil’s artistic lineage to life. Through 137 archival photographs and eight original paintings, the exhibition, organised in collaboration with the Ferenc Hopp Museum of Asiatic Arts in Budapest, reveals the deep cultural dialogue between India and Hungary. It highlights the creative influences of Amrita’s father, Umrao Sher-Gil, whose painterly photographs form the heart of the collection, and her uncle Ervin Baktay, whose intellectual mentorship shaped her vision. Spanning Lahore, Budapest, Dunaharaszti, and Paris from 1889 to 1954, these rare images offer a deeply personal window into the world that nurtured one of India’s most iconic modern artists.

Among the highlights of the exhibition is Ancient Storyteller (1940), one of Sher-Gil’s quieter, more contemplative works. In a dim village courtyard, an old man sits cross-legged mid-gesture, surrounded by children listening intently. A woman in a red shawl faces an earthen pot and a mortar and pestle – her day’s work laid out and ready for her. Rendered in flat, earthy tones, the scene hums with stillness and presence. There is no drama, just the weight of a story being told and remembered.

“Amrita is the real link between today’s Hungary and India — our strongest cultural connection,” said Mariann Erdő, Director of the Hungarian Cultural Centre. “For us at the Liszt Institute Hungarian Cultural Centre Delhi, her Hungarian side is central. Many don’t know she was born in Budapest and spent her first eight years there. Hungarian was her mother tongue — she spoke it with her family and even wrote many of her letters in it. Our aim is to highlight the Hungarian Amrita.”

Sher-Gil’s influence is also institutional. The Amrita Sher-Gil Cultural Centre in Budapest, established by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, continues to promote intercultural dialogue between India and Hungary—two homelands that shaped her soul. Hosting art exhibitions, lectures, performances, and film screenings, the Centre is a tribute to Sher-Gil and a torchbearer of her enduring artistic legacy.

The Sher-Gils’ world

The photographs of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil—a philosopher, scholar, and deeply introspective father—captured not just moments, but moods. Quiet, intense, and alive with spiritual energy.

“He was a spiritual artist,” said a guide at NGMA. “Because whatever he wanted to write about—what he was reading, what he saw in life, what was there, what wasn’t there—he was a spiritual mentor. He wanted to tell himself how life changed. So, it’s related to this.”

The domesticity in these photographs—Amrita and her sister Indira in costume, or caught mid-thought—shows a family in reflection, and the quiet emotions behind daily life. “One can see that from childhood, they used to dress up. Umrao has taken photographs of them and himself. Baktay has taken photographs of the family,” the guide said.

Baktay, Amrita’s maternal uncle, was another central figure in her life. A Hungarian polymath and Indologist, Baktay’s immersion in Indian spirituality left a profound mark. According to the NGMA guide, “He followed Shiva. He read a lot of books. He was a Hindu follower. So, he wrote a lot of books.” One photograph shows him holding a painting of Shiva he made himself as a visual anchor to his inner transformation.

His travels, too, tell a story. Arriving in India in 1927, he explored the country with a curious eye—the Taj Mahal in Agra to the Shalimar Bagh in Lahore. A year later, he visited Jantar Mantar and Gandhi Smriti in Delhi—places that quietly began shaping his artistic vision. He journeyed to Gulmarg, Kashmir, where much of his writing took form. By the 1930s, his path stretched from the valleys of Kashmir to the plains of Punjab, each stop leaving its mark on his evolving work.

Baktay didn’t just study India; he became part of its philosophical fabric, infusing the Sher-Gil household with a spirit of cultural synthesis that would later find voice in Amrita’s art.

Also read:

A brush against convention

Four women stand in hushed stillness, draped in heavy folds that fall like shadows. One clutches a terracotta pot, another rests a protective hand on a child’s shoulder. Their faces—elongated, solemn, turned inward—speak of quiet sorrow. Eyes downcast, bodies thin, they seem alone and yet bound by a silent, shared weight. Light and dark press against each other, heightening the tension. They don’t pose—they endure, absorbed in a world of their own, wrapped in silence, dignity, and an unspoken bond.

This is Hill Women, one of Amrita Sher-Gil’s most powerful works, painted in 1935 during a winter spent in Shimla. Though she claimed that there was no story behind it, and that it was “purely pictorial,” the emotional weight of the painting is undeniable. The image was inspired by the poor people surrounding her home in Shimla. Sher-Gil captured their sadness and grace without resorting to sentimentality. Exhibited in Paris, Hyderabad, and Lahore, and later honored on an Indian postage stamp, Hill Women endures as a quiet, haunting portrait of strength in stillness.

Amrita’s artistic journey was a quiet turning inward, from the polished techniques of European academic art to the muted, earthy tones of Indian life. Her palette softened, her figures grew stiller, and her gaze turned empathetic, no longer observing from the outside but painting from within. This shift finds its poignant conclusion in her later work (Three Girls by Amrita Sher-Gil, 1935 ), where intimacy replaces spectacle.

Her reputation as one of India’s foremost modern artists has long rested on her vibrant canvases and European training. In early 20th-century India, where women artists were often sidelined, Amrita carved out a fiercely independent path. Educated at Paris’s École des Beaux-Arts, she absorbed European modernist techniques, only to return home and reimagine them with Indian themes.

Her feminist stance wasn’t limited to what she painted, it extended to how she lived. Vivan Sundaram, Amrita’s nephew, extends this legacy with his exhibit, Re-take of Amrita. His digital photomontages transform old family photographs into new compositions—Amrita laughing, Amrita reposed, Amrita multiplied—creating uncanny dialogues between generations.

“From my visits to Indian schools and universities, it’s clear that Amrita is far more celebrated in India than in Hungary,” said Erdő, adding that “India has, in a way, ‘privatised’ her story — often without mentioning her Hungarian roots.”

In an increasingly polarised world, Amrita Sher-Gil’s life and art offer a timeless reminder: that identity can be fluid, heritage can be hybrid, and expression, above all, must be free.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)