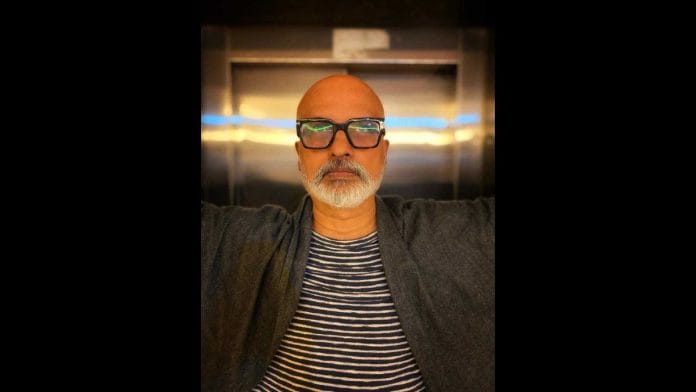

Kozhikode: Jeet Thayil and poetry broke up in 2008. In 2020, they got back together again. And like most people who go back to their exes, it had something to do with an extended period of solitude—and India’s political climate, said the poet and author.

The break up wasn’t voluntary, he clarified. Poetry had just stopped coming to him for 12 years and then the tap opened again.

“If you receive a poem, all you can do is quickly make a record of it,” he said. He added that you can’t just passively wait around either. “If you want to get struck by lightning, you have to go to the mountaintop. Be open to it,” he said.

And once he had around 20 poems, he had to honour them in some way. It’s what led to Thayil’s comeback poetry book, I’ll Have It Here.

Released in November 2024, it was the topic of discussion during his session at the Kerala Literature Festival in Kozhikode this year. In the book, he turns a mirror to the country and himself. Gandhi is reborn as a house gecko, the government is fake and his love grows wings and flies away. The pavillion was overflowing with people, with many resorting to sitting on the floor. The residents of India’s only UNESCO City of Literature eagerly listened as Thayil recited his poems, tapping their feet to the rhythm.

“It has a sense of humour, which is new to me,” Thayil said. What’s old is his strict adherence to form. All the poems have a rhyming scheme.

“A strict form is liberation. The poem writes itself,” he said.

And all other rules are broken for the form. It’s why Thayil considers the language in the book as “post-language”. Words are misspelled for the rhyme, the mood comes above the words used. For example, in the poem December 2020, plague is rhymed with plague multiple times.

Poems are prayers

Poetry is one of the few activities in the world that is done without the thought of money, said Thayil. And anyone who writes poetry for it is out of their mind.

“If poets ever get money it’s so late they don’t know what to do with it. If they get fame, it’s so late they don’t care about it. It’s something to admire,” he said, “Unlike novelists.”

But poems endure because they’re a source of comfort. People turn to them in times of crisis, he said talking about how the newspapers in New York started carrying poetry after 9/11.

“We go to poems for the same reason we go to prayer,” said Thayil.

Also read: AI Mona Lisa to touchscreen Last Supper, Da Vinci goes hi-tech. Some call it ‘dumbed down’

Saved by Instagram

Around the time he started writing this book, Thayil, in an interview with The Guardian, said that important Indian poets are unable to find publishers.

Five years on, his opinion has completely changed. He pointed at independent publishers, and added that even the mainstream publishers are printing more poetry.

“They’ll tell you that they don’t because they don’t want to get hundreds of manuscripts. So they lie and say, ‘no, no, we don’t publish’, but they do,” he laughed.

Thayil attributes the change to an unlikely source — Instagram.

“It celebrates short form. You can read an entire poem in a post,” he told ThePrint. Thayil is delighted at the kind of exposure to poetry it’s brought to young people. They post poems, he said, “poems by poets that only I thought I knew!”

Thayil added that his trajectory as a poet might have been completely different if there had been an app like Instagram when he was growing up.

“I certainly know that in the case of friends of mine, if there had been something like Instagram in the 80s, they might still be alive.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)