New Delhi: Humayun’s Tomb is more than just an architectural marvel of white marble, red sandstone, and lush gardens. Its grandeur is enriched by the intangibles: the aroma of Mughal food cooked by basti women, the rhythmic songs of Sufi saints, and the oral histories passed down through generations.

In the auditorium of the Humayun Tomb Museum, Dr Niyati Jigyasu spoke about the role of intangible cultural heritage in preserving and managing historic cities across Asia. She was speaking at Conversations on Conservation, a discussion about the book Sustainable Management of Historic Settlements in Asia.

As one of its editors, Jigyasu took the audience through each chapter to explain how intangible cultural practices—such as traditions, rituals, and expressions—interact with architecture and urban layouts.

Co-edited by Anjali Krishan Sharma, the book is a compilation of essays by architects and conservationists from India, Italy, Japan, Indonesia, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Thailand, each examining different aspects of how cultural heritage shapes the preservation of historic cities.

Joining her on stage were KT Ravindran, former head of Urban Design at the School of Planning and Architecture, and Dr Madhura Dutta, a culture and development specialist. The audience, though small, was highly engaged, peppering the panel with questions. Among them were fellow conservationists, architecture professors, and Ratish Nanda, CEO of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, who had contributed to the book.

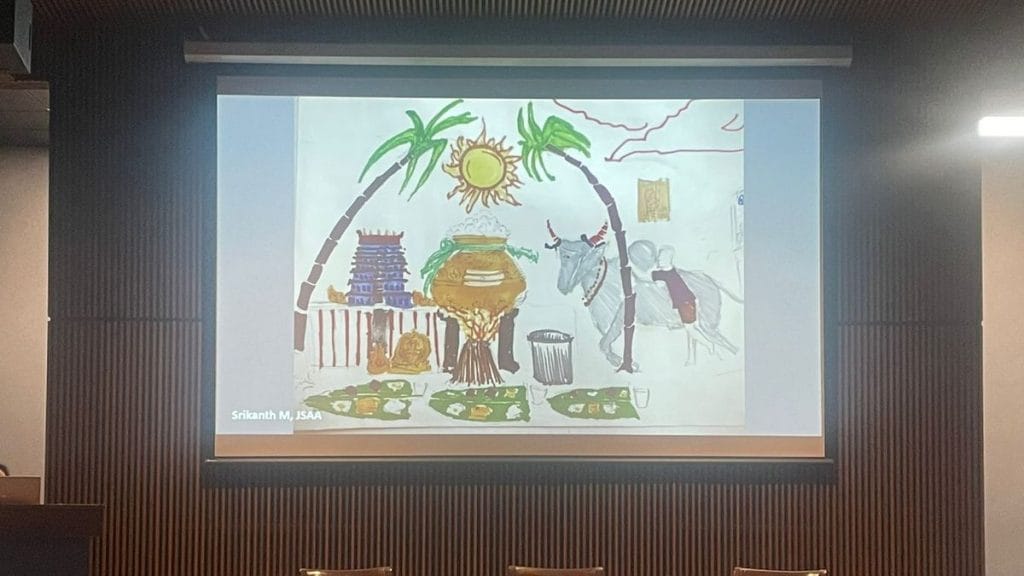

To illustrate her point, Jigyasu presented a painting of the South Indian harvest festival Pongal at a temple by Srikanth M, a student at Jindal School of Art and Architecture.

It depicted traditional dishes made from newly harvested rice, jaggery, sugarcane, and vegetables. A boiling pot of milk, considered auspicious and representing prosperity, occupied the centre. A book dedicated to a Tamil poet and a bull-taming event took up the right side.

“The most interesting part is the scale of the temple in comparison to the intangible elements,” said Jigyasu, pointing to the traditional Tamil temple rendered much smaller than the rest of the elements of the painting.

Also Read: Russian ballet meets Kathak in Delhi. It’s a confluence of traditions, art, music

When people power heritage

Local communities are not just residents but important custodians of intangible heritage. According to Ravindran, this is best exemplified by the work done by the Aga Khan Foundation in Nizamuddin basti.

“The setting up of the Zaika-e-Nizamuddin, with women cooking traditional Nizamuddin food, not Mughal food, is a fantastic achievement,” said Ravindran. “I often order food from there myself.”

He added that other women-led initiatives— including building women’s gyms and parks—have helped boost the economic development of the locality and created a sense of ownership.

At Humayun’s Tomb, this change is evident in the profile of visitors.

“A lot of the people who (come to) this place are people from the basti,” said Ravindran. “You can see it in the way people are striding into the monument. Families are coming in for picnics, feeling that ‘this is my heritage’.”

Madhura Dutta offered another example of community engagement. At Borobudur Temple in Indonesia, local artisans developed special footwear for entering the temple.

“I love how it addresses both the local economy as well as preservation of the temple stone structure,” she said. “It shows how the local economy can be integrated into the conservation and sustainability process.”

Also Read: Tree trunk to stone to human face—how deity worship evolved in Hinduism

Double-edged sword of tourism

The beautification of heritage sites to attract tourists generated a lively discussion. The ‘facelift’ given to the area around Amritsar’s Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple), for instance, raised questions about balancing preservation and commercialisation.

“That project has made it into a tourist island, a Disneyland,” said Jigyasu. “Someone from the media said it looks like a film set.” Yet, she noted, tourists seemed to love the changes.

Jigyasu cautioned that while intangible cultural heritage (ICH) creates jobs and drives footfalls, over-commodification of it risks damaging the very resource tourism is dependent on.

Ravindran described the Amrit Sarovar, the sacred reservoir around the Golden Temple, as “one of the most beautiful places in the world”. He expressed his relief that it had remained untouched by the beautification project but rued that some of the intangibles had been lost.

“They have done away with the fine texture of the streets, the paratha places, local shops which people had connections with,” said Ravindran. “It was a highly walled street where the tangible and intangible were so completely mixed.”

Now, he argued, it has been stripped down to its façade, with only fragments of the intangible left.

“I don’t agree with it,” he said. “But people (tourists) love it because they are not invested in it. Those who are invested are the ones who are fighting it in court, local people whose lives were affected by what was done on the street.”

The author graduated from Batch 1, ThePrint School of Journalism.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)