When economist Pranab Bardhan got a chance to speak in front of Sonia Gandhi at a conference in Delhi back in 2010, he decided to “provoke her” with a lecture on decentralisation. The Congress leader did not respond; she quietly shook his hand during the coffee break and walked away.

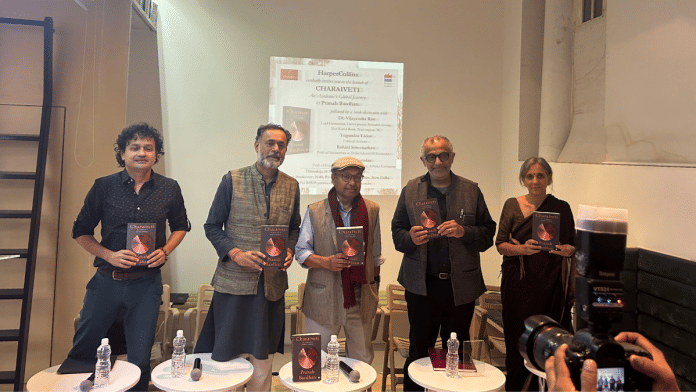

Thirteen years later, Bardhan maintains his stance—that India needs decentralisation. Vignettes like his interaction with Gandhi have found their way into his memoir, Charaiveti: An Academic’s Global Journey, whose launch at Delhi’s Oxford Bookstore saw Bardhan reiterate his views.

“In the late 1990s and early 2000s, I did more surveys where the topic was decentralisation and the panchayat system of the government. I started to understand the concerns of people in a deeper sense,” the octogenarian professor emeritus of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, said.

He supported his assertion by looking at the challenges of the Indian population and democracy. “In a country of 140 crore people, the local diversities are so staggeringly large that it is impossible for any central (or even state) government, for all their Vedic wisdom, to know what is good for all the different communities and how to implement policies in the local context,” he later told ThePrint in an email response.

It’s the excessive control exercised by the central government that hinders the India growth story, the professor said.

Movement and change

There’s a deep sense of movement in Charaiveti as Bardhan draws from his early years in Kolkata and Santiniketan, his time in Delhi and Kerala, and later at Cambridge, Massachusetts, and California. His travels to Beijing, Paris, New York, Barcelona, and France find mention in the book. And the trope of movement inspired the title too—charaiveti is a Sanskrit word that means ‘keep moving’ in the quest for self-realisation.

Bardhan left Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and returned to India to conduct village surveys measuring poverty. He wanted to research how landlords, employers, and moneylenders exploit the poor and what kind of benefits the exploited receive from the local governments.

For the past four decades, poverty has been steadily declining in India largely due to a rise in agricultural productivity, improvements in transport and communication infrastructure, and some landmark welfare policies.

But Bardhan says it’s not enough. He would rather have land reform, improvements in the quality of education and healthcare, vocational skill-formation, encouragement of labour-intensive but high-quality methods of production, technological extension services along with credit, and marketing support to small and medium-sized enterprises.

To enhance the effectiveness of local governance, it is crucial to empower institutions like Gram Panchayats with more authority and resources, enabling them to better serve their communities.

While the Panchayati Raj and municipality systems aimed to empower local governance, Bardhan said they have not yet been very effective in many states. “Kerala is probably the major state in India that has the most effective decentralisation,” he added.

And it’s the lack of political will that prevents decentralisation from becoming a reality. “The government is more into manipulating numbers, running away from unflattering data, and considering welfare policies as gifts from the supreme leader,” he said.

Longing and hope

Charaiveti takes the reader around the world, but India remains the focus. There’s a yearning for a home in India throughout the memoir.

“This longing on the part of the deracinated in melancholy exile and yet disappointed with one’s own origin country is not unfamiliar to me,” he writes.

Saikat Majumdar, author and English professor at Ashoka University who attended the launch, compared the book to a novel, one that highlighted many “cosmopolitanisms”—from literature to culture. Political scientist Yogendra Yadav, who was one of the speakers at the event, praised Bardhan for his judgement.

“When I look at him, I see that judgement being exercised. And that’s why I see this book as a journey of a very Indian, very desi and very modern intellectual,” said Yadav.

Seeing the large gathering at Oxford Bookstore, Bardhan joked he felt as if was attending his own funeral.

The funeral of an individual who lived everywhere and yet nowhere. “First-generation immigrants like me have a particular restlessness—that they are at home nowhere,” he said.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)