New Delhi: A group of writers, academics and activists gathered one winter evening to celebrate the launch of the book This Too is India: Conversations on Diversity and Dissent, which started as conversations over cups of tea.

The event, held on 9 December at Jawahar Bhawan, was attended by a mixed crowd of over a hundred journalists, academics, activists and students — the stalwart defenders of dissent and democracy in India sitting alongside the youth.

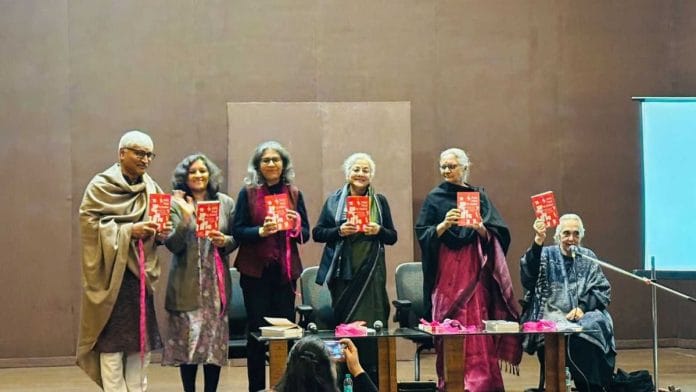

On stage was a refreshingly all-women panel: historian Romila Thapar, journalist Seema Chisti, lawyer and activist Usha Ramanathan, and the editor of the book, writer Githa Hariharan. The book, This Too is India is the Indian Cultural Forum’s last hurrah: it is a now inactive website set up in 2015 by writers, educators and cultural practitioners to highlight the importance of India’s rich and plural heritage.

“The urgency and fear we felt developing at that time is what pushed us into acting firmly and making something of a tea-time conversation,” said Thapar, who gave a lecture before the panel had a discussion moderated by Ramanathan. “These days, they say the academic historian can’t talk to the public — which is ridiculous because we spend all our lives talking to the public. But okay,” shrugged Thapar, as the audience laughed. “We’ll continue to talk.”

The event was the fourth edition of Conversation in Context, hosted by Nehru Dialogues and Westland Books, which published This Too is India.

As the panellists discussed the importance of keeping a cultural conversation alive in India today, they fell into their own professional roles — the academic Thapar, the literary Hariharan and a more urgent Chisti, all moderated by Ramanathan’s analytical questioning.

“Everytime we speak, we call it dissent. But in my understanding, in a democracy people speak and representatives listen,” said Ramanathan during the discussion. “We call it freedom of speech, but every time we speak we call it dissent. Why?” she asked.

Chisti objected to the title of the book, and the inclusion of the word ‘too’ in This Too is India.

“We’ve perhaps bought into the idea that there’s a right way of saying things and the rest of us are doing the item number dance of dissent!” said Chisti.

Also read: John Lennon wrote a song full of expletives called ‘Maharishi’. Then he had to tone it down

The historical method

Thapar gave a rare public lecture at the launch, and the audience hung onto her every word, craning forward to listen to her talk about the importance of alternative stories — and the role they play in constructing a historical narrative.

But it’s the method that determines the kind of history one is seeking to write, not the ideology, said Thapar.

“Some historians in private conversations have lots of pipe dreams, but they don’t claim it’s history,” said Thapar. “And this distinction — this right to assert what we wish to write — is strong because of social media today.”

She pointed to the origins of the Indian Cultural Forum, and the anxiety that led to its origins. Thapar, Hariharan, and others — including Nayantara Sehgal, K. Satchidanandan, Nandini Sundar and T.M. Krishna — formed the site and Guftagu, on which they published several of their works. The primary goal was to encourage conversation between people thinking about the various cultural and sociopolitical changes taking place in India.

Thapar talked about how during one of those conversations, mentioned a story that fascinated her: the story of Mahmood of Ghazni raiding the Somnath Temple, a story that’s now being revived as part of India’s cultural history, and that she’s written about in her book Somanatha: The Many Voices of a History.

The Persian texts have a straightforward version of the story: Mahmood raided a temple because it was wealthy and it was on an important trade route. The Sanskrit texts don’t mention the Somnath temple at all, only mentions of Mahmud raiding other temples.

A 13th-century Jain text bears witness to the disrepair the temple was in, as it was neglected and the sea weathered the stone — but it doesn’t mention a raid. Yet another 13th-century bilingual inscription of a trader from Iran mentions that he asked the local administration to give him a patch of land to build a mosque for travellers and sailors to worship at, and the land he was given was part of the estates of the Somnath Temple.

It was 500 years after this, said Thapar, that the issue of the raid on Somnath Temple truly became an issue. It was raised in the House of Commons in London in the 19th century by British administrators who argued the event caused trauma to the Hindu community — and this is where the narrative of the temple’s desecration began.

“I think it’s important again to question this description of alternate readings and then to discuss to what extent these alternatives are dissenting views. I would argue that these alternative versions are in part dissent,” said Thapar. “This is the kind of problems we historians face, because it’s not easy to separate the fantasy of a history from a fantasy of a community, and we have to be careful to make that separation each time.”

The importance of dissent

The event was like any other semi-academic, semi-activist event in Lutyens Delhi. The difference is that it hinged not on action, but on the immediate everyday activity all citizens can do: think, and talk to each other.

“When we set up the Indian Cultural Forum, we were a bunch of academics and writers and all we had were words. But what does it mean to actually live it? Even those of us who think we’re engaged citizens find it difficult to negotiate a multilingual India,” said Hariharan, mentioning that one of the first things they did as a group was draft 17 versions of the common letter they sent to the Sahitya Akademi regarding MM Kalburgi’s murder. “We were learning on the job!”

While the panel touched on how India today is vastly different from the India they knew — both culturally and politically — they didn’t glorify the past.

“I think the beauty of the book is that it deals with the imperfections of India before 2014,” said Chisti. “We’re standing at a point where the idea of equality is being undone. The system behaves how the bully behaves. It’s important to retain perspective on what 2014 was, and what was before that.”

They also talked about how reconsideration and revisiting ideas is important to push conversations forward.

“The mainspring of something like the Indian Cultural Forum was that we asked questions about creation and creativity, and tried to think about redefining culture, which like society, like history, is constantly changing — it’s not static,” said Thapar. “And the fundamental thrust of the thinking is that silence is not what we live for.”

The conversation came back to the same point: the importance of conversation in the first place. “Conversation is a brilliant method where you think deeply. Are these conversations still possible?” asked Ramanathan.

“They must happen,” said Thapar in response. “Otherwise you give up.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Romila Thapar does not know Sanskrit. How were Sanskrit texts interpreted by her? Through useful translations? What texts were considered, those that supported her arguments? Were the rest considered less than reliable? This nonsense has been perpetrated too long. Secularism has turned in to Muslim and invader worship by these so called scholars. Seema Chisti, connected to the Chisti Sufis. Can we have an article about how Ajmer sexual exploitation was suppressed in the name of secularism? This is a modern example, when Muslims are not in power. When they were in power how much book burning and suppression were we dealing with?

The Usual Suspects.

One can only wonder what makes The Print devote so much time and space to these people.