New Delhi: At the launch of Tarini Mohan’s memoir Lifequake: A Story of Hope and Humanity, former Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud made an important observation: for many people with disabilities, the greatest struggle isn’t their impairment, but the barriers society puts in their way. When mobility aids are taxed or access is limited, it sends a clear message — that full inclusion isn’t a right, but a privilege reserved for a few.

“It’s the attitudes, the lack of accommodations, the suffocating frameworks built by society that hurt the most,” Chandrachud said. Lifequake, he added, feels like “tuning into the daily symphonies of microaggressions — exclusions, stairs without ramps, cafes without braille menus, recruitment panels that see disability as a deficit rather than diversity.”

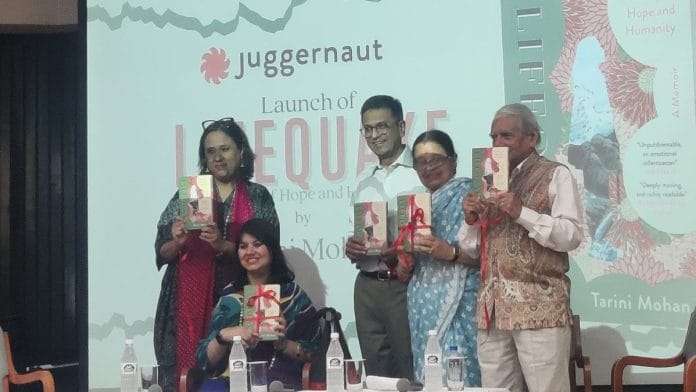

Mohan’s memoir was launched on 18 July at Delhi’s India International Centre in the presence of former CJI Chandrachud and journalist Barkha Dutt. The event was a tribute — not just to Mohan’s resilience, but to the doctors, friends, and family who stood by her through her long recovery. The hall was packed, with people lining up for autographs and teary-eyed listeners, including Dutt, visibly moved by the story. The evening ended with a standing ovation, a collective salute to Mohan’s courage and her powerful act of storytelling.

Lifequake is about rebuilding a life from the ground up. Waking in a body she no longer recognised, Mohan slowly pieced herself back together, even writing the book with her left hand after losing function in her right. The memoir’s power lies in quiet, honest moments — a mother’s touch, the ache of loss, and the daily choice to keep going.

“I don’t want to be an inspiration to other people, I just want this story to be about me,” said Mohan.

Love in the time of limbo

Mohan’s mother Rasika, a Bharatanatyam dancer and teacher, turned to the rhythm of shared memories to reach her daughter. Sitting by her bedside, she tapped out the notes of Kalyani Jathiswaram on the bedframe: Sa Ni Dha Pa Dha Ma Ga Re Ni Re Sa. Somewhere between her determined tapping and whispering “Nyari, I love you”, Mohan’s eyelids flickered.

What followed was not a straight path to recovery, but a zigzagging one — through confusion, pain, memory loss, and physical immobility. Each minor improvement was a milestone: remembering a phone number, forming a sentence, moving a limb.

While doctors offered no certainty about her prognosis, the family held on to hope. Her hospital room was a fog of white and time stood still. Nurses changed diapers, braced her limbs, and rolled her gently as her eyes welled up from the pain. But inside her mind, Mohan believed she was dreaming. “It doesn’t matter. I’m in a dream. I know where I actually am — asleep at home in NYC, with Nikhil by my side.”

In the months that followed, her relationship with Nikhil, her partner, ended.

“I felt a giant pressure on me to fully recover, to get back to square one, when square one was hard to reach. I thought it was a wise decision. I still love him and he still loves me but the form of love has changed,” she said.

Born and raised in New Delhi, Mohan began her career at Morgan Stanley during the 2008 recession, but soon pivoted to international development work in Kampala, Uganda. Just six weeks in, a road accident left her with a traumatic brain injury and she slipped into a coma for three months. Despite lasting physical and cognitive challenges, she went on to earn an MBA from Yale School of Management in 2020. Waking from the coma wasn’t a cinematic triumph, but, as she writes in her memoir, “a painstakingly slow and frustrating process”, far from the sudden ‘aha!’ moments seen in films.

Today, Mohan serves as Manager, Disability Inclusion in Higher Education at 9.9 Education, helping shape inclusive practices in Indian institutions.

Also read: Dalai Lama’s sister is the subject of new documentary. ‘She nurtured a generation in exile’

Acceptance and possibility

Despite everything, bitterness never found a home in her story. Lifequake is not mournful — it’s quietly defiant, sometimes even playful. “Mmmm… jelly,” she croaked the first time her mother asked her what she wanted after waking up.

At first, she struggled to believe that her right hand’s paralysis was permanent; it felt like something that only happened to other people. During her long months of treatment at Max Hospital in Delhi’s Saket, as she stood near the Qutub Minar, she saw something deeper in its endurance. “When I look back, I feel there is a theme of power of continuity in Qutub Minar. It has stood through all times,” she said.

At the book launch, Chandrachud called Tarini Mohan’s memoir “a gathering of hope, resilience, and a call for transformative change.” He praised the book as a “manifesto against reductionism” — an insistence that no label, disability or incident can define the totality of a person.

He spoke of the systemic failings that continue to marginalise people with disabilities — from inaccessible pavements to outdated recruitment criteria. Drawing parallels with Mohan’s experience, he referenced a young medical aspirant with 88 per cent locomotor disability who was denied admission based on rigid guidelines. “The Court insisted that what matters is not what a person lacks, but what they can do with support, with planning, with ingenuity.”

Speaking not just as a jurist but also as a father, the former CJI offered a deeply personal reflection on parenting children with disabilities. His daughters, Priyanka and Mahi, have Nemaline myopathy — a rare genetic disorder that weakens skeletal muscles and requires the person to have constant care, accessibility support, and specialised attention.

He recalled a family holiday in Shimla when his daughter developed severe respiratory distress. The doctor said, “This is the worst case. We’ve ventilated her. She won’t survive here for five minutes. We need to take her to PGI Chandigarh.”

It was their younger daughter who urged them forward, and they made the three-and-a-half-hour journey to Chandigarh holding on to hope. At PGI, his daughter spent 44 days in the ICU.

“As parents, you never give up hope,” he said. “Very often, doctors — even in public hospitals — ask, ‘Why are you doing this? This is a lost cause.’ That’s when you have to stand firm. It’s not in your hands or mine. We do our best, aware of the situation, but with faith in the goodness of human existence.”

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)