New Delhi: The notion that the protesting youth in Nepal are anti-democracy is absolutely wrong, said former chief election commissioner SY Quraishi before a room full of former civil servants and researchers who had come to listen to a discussion on democracy in the Indian subcontinent.

Quraishi has family ties in Nepal, where he saw the youth not rejecting democracy, but demanding a cleaner, more accountable version of it.

“Some people think that this is a setback to democracy, and the youth are anti-democracy. It is absolutely wrong. They are very much pro-democracy, but they want better democracy — an honest democracy,” he said, recalling how young people in Kathmandu took to the streets not just to protest but later to clean them up, demanding integrity in governance.

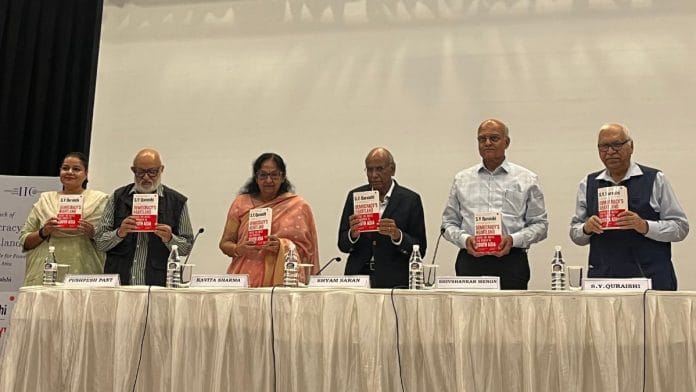

Quraishi chose the International Day of Democracy to launch his book Democracy’s Heartland: Inside The Battle For Power in South Asia, published by Juggernaut Books. The timing of this launch was appreciated by the audience. The recent Nepal political churn, along with the turbulence in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, had made a discussion on the subject necessary.

“Forty per cent of the world’s democratic population lives in just eight countries of South Asia,” Quraishi said at the Delhi launch. “Yet there is hardly any global recognition of this fact. My attempt is to highlight why this region matters and what lessons it can offer.”

In 2015, when the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) offered a fellowship to Quraishi at King’s College London, he picked a topic that was too vast for a quick research paper — democracy in South Asia. The research paper was supposed to be wrapped up in about 20 pages, but that exercise ended up taking more than a decade of research and travel. Now the result is Democracy’s Heartland, a book that repositions the region as democracy’s crucible.

Quraishi said that while free elections were essential, they were never enough.

“A good election does not mean a good democracy. In India, 45 per cent of MPs face criminal cases by their own affidavits — and yet they come through free and fair polls. That is why institutions, not just elections, are vital,” he said.

An ‘anti-democratic shift’

More than 200 people had gathered at the CD Deshmukh Auditorium of the India International Centre — from former bureaucrats to researchers and students — to attend the discussion chaired by former foreign secretary Shyam Saran and moderated by . The discussion was moderated by food critic and historian Pushpesh Pant. The panel also included former NSA Shivshankar Menon and former president of South Asian University Kavita Sharma.

Saran called the book “opportune and prescient.” Drawing on recent democratic reversals, he warned of “a dangerous anti-democratic shift” — from dynasties and corruption in the subcontinent to populist strongmen in the West. “Even in the crucible of democracy, the United States, many values are being abandoned,” he said. “But this is not the only trend. As Dr Quraishi shows, what happens in South Asia is absolutely critical for the future of democracy globally. If democracy does not succeed here, it will struggle elsewhere.”

Saran also underlined what he called the “recurrence of the democratic instinct.” Sri Lanka’s protests, Bangladesh’s unrest, and Nepal’s generational shift, he said, may look destabilising but reveal how citizens return to democracy the first chance they get. “That instinct is very strong in this region. As long as it survives, there is hope.”

If Saran found optimism, Pushpesh Pant probed weaknesses. He praised the book as “persuasive and elegant” but argued that the Election Commission is not the sole bulwark of democracy. “The bigger threats are corrupt oligarchies, entrenched elites, and crony capitalism,” he said, pointing to the hypocrisies of global powers who push “friendship between rivals” abroad while failing to practice it themselves.

Also read: ‘In an ideal world, there would be 10-15 Muslim women in each Parliament’: Omar Abdullah

Optimism

During the book discussion, Quraishi shared anecdotes from his travels to Sri Lanka and Nepal.

The former CEC met Mahinda Rajapaksa after he lost the 2015 Sri Lanka presidential elections. “He told me bitterly, ‘I lost not to my rivals but to RAW.’ Five years later, before the next election, I asked him again and with a wink he said, ‘No, now we are friends’,” Quraishi said, drawing laughter. In Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina once told him, “The day I see Biden and Trump hugging each other, I’ll hug Khaleda Zia.”

Saran agreed with Quraishi, but cautioned against idealising the young. “They are no monolith. Social media can both empower and polarise,” he said. “But a critical mass is enough to push change.”

The discussion returned repeatedly to institutions. Quraishi pointed to how Nepal’s collegium-style system of appointing election commissioners ensured credibility, while India — the world’s largest democracy — still relied on political discretion.

“The constitution gave me protection,” he said of his own appointment. “Once I sat in the chair, I could act independently. But the process must itself inspire trust.”

In the end, the discussion circled back to the reminder that democracy in the Indian subcontinent remains fragile yet resilient.

For Quraishi, the lesson is simple: “Everywhere in the world democracy seems in retreat. But in South Asia, the first opportunity people get, democracy bounces back. That is the optimism we must live up to.”

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)