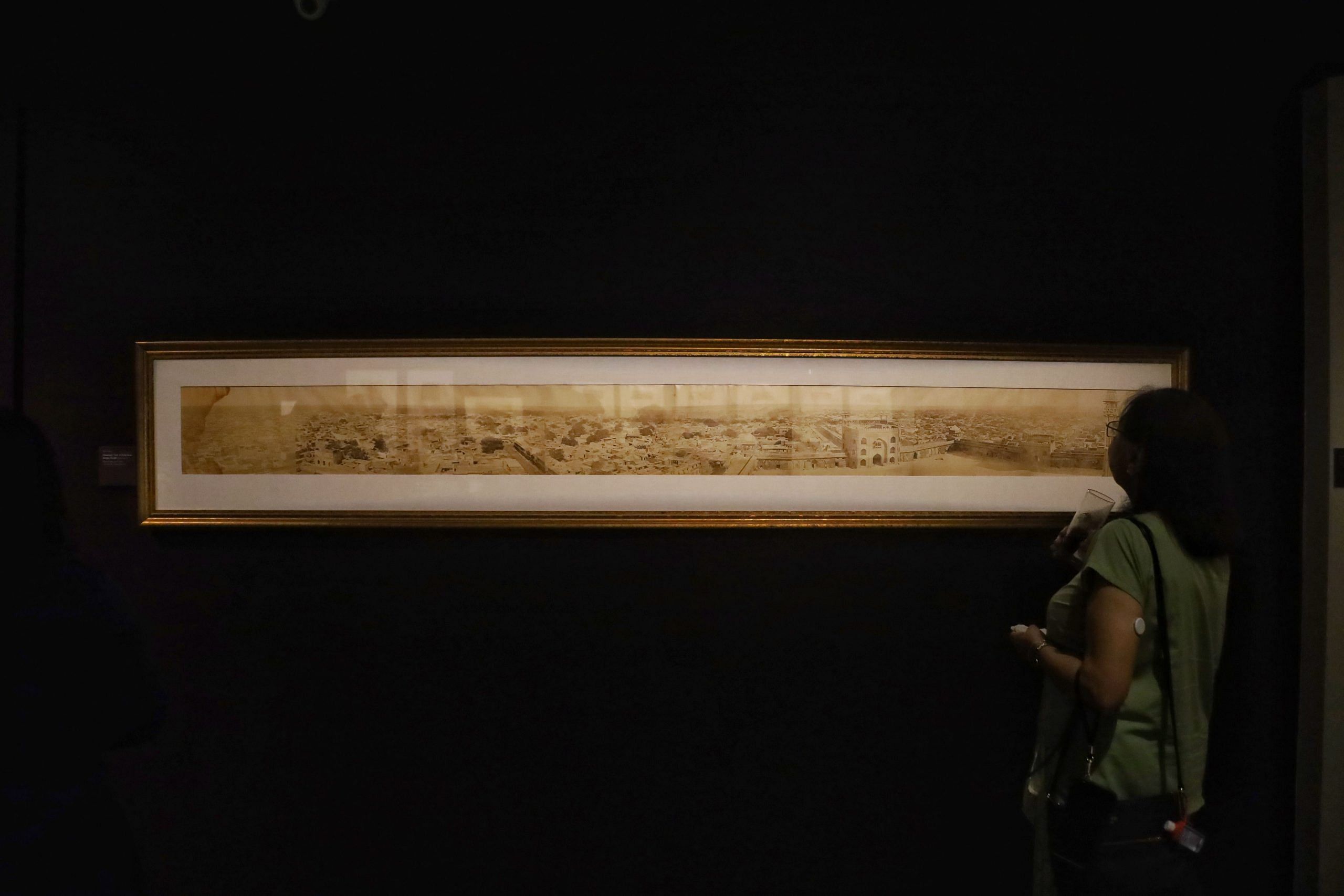

New Delhi: Following the 1857 revolt, an Italian-British photographer captured a panoramic view from Delhi’s Jama Masjid. At first glance, this historic image appears to be a vivid documentation of Indian monuments and cityscapes, but a closer look reveals the missing element: people.

Felice Beato’s photograph is one of many showcased in the exhibition Histories in the Making: Photographing Indian Monuments, 1855-1920, organised by DAG and on display until 12 October. The collection, sourced from DAG archives, weaves together the interplay of politics, fieldwork, history, and archaeology.

Curated by Sudeshna Guha, former curatorial manager and research associate at the University of Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the exhibition explores the connected histories of archaeological surveys in India.

“It alerts us to look for the many narratives a photograph carries, often through its life histories. Photographing, it reminds us, is an act of staging reality, and we gauge photography’s inordinate legacy of facilitating subjective viewing into objective narratives,” Guha said.

Missing context

Beato, a war photographer, arrived in India toward the end of the revolt and aimed to capture the immediacy of the events. He travelled across Delhi, Kanpur, and Lucknow, predominantly capturing landscapes and monuments without human figures. It is unclear whether this absence was intentional, given that the photographs were used in archaeological surveys.

“The sweeping views and ‘depth of field’ convey the ‘illusion of continuity in time’ and a ‘sense of narrative’. However, the imagery is strikingly bereft of people, and thereby provides, contrary to Beato’s intentions, a high vantage point for seeing the brutality of British reprisals, which entailed cleaning the mutinied cities by killing the rebels and by forcible evacuations,” Guha writes in the book Histories in the Making, which lent its name to the exhibition.

Critics have labelled Beato’s approach as “orientalist.” In their book Beato’s Delhi: 1857 and Beyond, historians Jim Masselos and Narayani Gupta point out the absence of local people in his images, noting that the focus is on battlefields and architecture. They suggest that such images were published in London newspapers to perpetuate the myth of British imperial power in the subcontinent.

While these photographs are living proof of the past and have significantly contributed to Indian archaeology, they lack captions to provide context.

Besides Beato, the exhibition showcases works by photographers such as Thomas Biggs, William Johnson, William Henderson, and Lala Deen Dayal. The gallery informs visitors about various photographic techniques used by these photographers, from early daguerreotypes to later innovations such as coloured collotype, halftone, and albumen prints.

Also read:

Photographic frenzy

In the 19th century, as photography gained momentum in India, more people began to view it as an act of creation. Indian photographers joined the frenzy as well.

“The photographic societies, we may suppose, allowed for some levelling up. Native photographers could display their work at par with the British, especially Company officers, irrespective of the racist milieu and colonialist mindset that regarded them, and ‘ladies’, as temperamentally unscientific,” writes Guha in History in the Making.

Yet, critics argue that the colonial and Eurocentric view—or the White gaze—persisted, even in the most picturesque Indian landscapes. Samuel Bourne, a banker-turned-photographer known for his soft and beautiful frames, documented his ‘Photography in the East’, which was published in ‘The British Journal of Photography’ between 1863 and 1870.

Bourne’s photographs, including those of Dal Lake in kashmir, the Ruins of Futtehpore Sikri (Fatehpur Sikri), and his best-known work, Himalayan Terrain, have been critically acclaimed, though they have raised questions that were overlooked at the time.

The only humans present in his pictures are coolies carrying photographic equipment, tents, and amenities against the backdrop of the Himalayas. The labourers are positioned in such a way that attention is drawn to them rather than the landscape. Bourne’s photographs clearly highlight the lurking inequities of wage relations. “It diminished the presence of people within them.”

Bourne’s exoticised portrayal of Indian landscapes inadvertently provided a commercial boost for Indian photographers. Softly toned photographs of Indian buildings, lakes, canals, and cities became popular souvenirs. Albums containing 20 to 100 pre-selected photographs were sold for Rs 50-200, often presented as cabinet cards—photographs mounted on cardboard with studio information and the photographer’s name.

Lala Deen Dayal, a prominent 19th-century Indian photographer, and others, such as HA Mirza, who captured the Delhi Durbar of 1903, benefitted from this commercial success.

(Edited by Prashant)

Do your homework!!! Cameras needed VERY long exposures so only stationary objects were registered on the emulsion. People moved so were not registered.

The early photography process required objects to be stationary for tens of minutes in order to be captured on film. The exposure time being so long, unless you posed people to be static for quarter of an hour or more, they would simply not register on the photographic plate. Even the early photographs of European streets do not show people for this reason. One famous early photo of a Paris street only shows a man getting his boots polished by another person, as these were the only people who were still in the same location for a quarter of an hour. The other people who were walking along the road simply did not show up in the image as the change in light falling on the plate was too transitory. It was only after fast acting photoactive emulsions were invented that you could get impression of moving people on your photographic plate. I am surprised that the exhibition curator does not know if this technical factor explaining the absence of people in all early panoramic photographs.

Wait a sec in 1857 there was no India people fighting were monarch and autocrats mentioned that