New Delhi: From the swirls of rangoli to the saffron flag, rosewater and rudraksh mala, ordinary objects have evolved into symbols of Indian heritage. Now, dedicated scholars at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, or BORI, have discovered references to such everyday items, documenting not just myths but the roots of India’s material culture.

The India International Centre (IIC) hosted the inauguration of The Future of the Past: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, an exhibition showcasing the history and cultural records preserved by the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune. Organised in collaboration with BORI and inaugurated by NN Vohra, Life Trustee, IIC, Pradeep Apte, Vice President of the Regulatory Council and Chairman of the Academic Council of BORI, the exhibition features reproductions of archival photographs, rare books, digitised manuscripts, and texts from BORI’s collection.

“Locked up with his manuscripts, he (Parshuram Krishna Gode) crossed the river to old Pune only thrice in his life,” Pradeep Apte, Vice Chairman of BORI, told ThePrint. “Gode used to refer to these as raddi (waste) jokingly, and yet, over decades, Gode meticulously traced the cultural and historical lineage of such items, recording nearly 600 papers about how ordinary objects evolved into symbols of Indian heritage.”

It’s BORI that has given this space to scholars for decades.

Past and present of BORI

Scholars at BORI have devoted decades to studying the hymns of the Rigveda and the narratives of the Mahabharata, unravelling their complex linguistic structures and historical contexts to make these ancient texts accessible to modern readers.

“BORI is not just an institution; it is a living entity, continually evolving as it bridges the ancient with the contemporary, the local with the global,” Apte said.

In 1860, the Bombay government recognised the irreplaceable value of India’s ancient knowledge and collaborated with Indian scholars to preserve manuscripts and texts, a rare convergence of colonial and indigenous interests driven by a shared reverence for knowledge. This resulted in the establishment of BORI in 1917 to honour the legacy of renowned Indologist Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarkar. He believed that to truly grasp the essence of India, one must delve into its ancient texts and timeless narratives.

Today, the institute houses over 28,000 manuscripts and more than 25,000 books, along with a vast collection of archival photographs. Many of the manuscripts are more than a thousand years old, written in a range of scripts from Devanagari to Sharada, preserving the diverse traditions of Indian knowledge.

But what sets BORI apart from other research institutions is its independence. “We are not a regular grant-in-aid institution like universities or government-aided bodies,” said Apte. “Since the beginning, we’ve operated with non-government private trusts and individual donations. BORI’s first major building, in 1917, was built with a donation from the Tata Trust, specifically for Avestan and Iranian studies.”

A pivotal figure in BORI’s evolution was Maharaja Kishen Prasad Bahadur of Hyderabad. In 1933, he commissioned the Nizam’s Guest House, designed as a hub for intellectual exchange where scholars could engage deeply with BORI’s vast collections. He also made a donation to support the publication of the Mahabharata, underscoring his dedication to preserving India’s literary heritage.

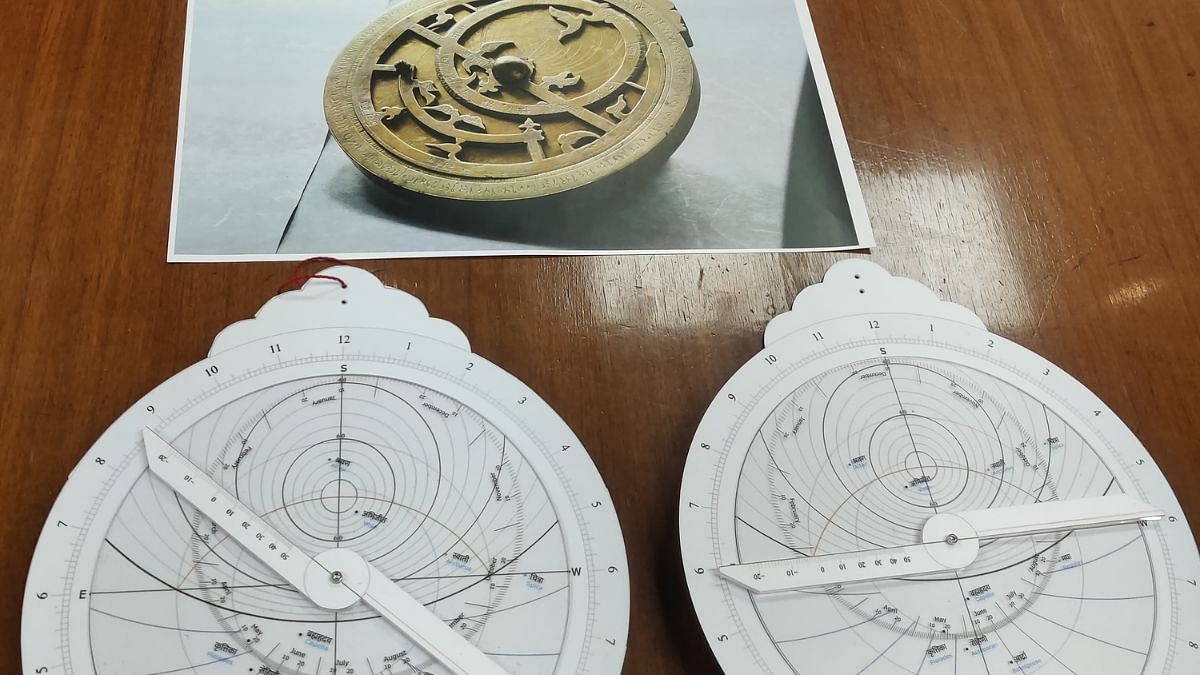

Among BORI’s impressive collection, the replica of the astrolabe stands out, the first of its kind crafted in India. This ancient instrument, which has a rich history dating back to the Hellenistic period, represents a significant leap in the field of astronomy. It took three years of research and craftsmanship to recreate this complex device, which can not only tell time but also determine Zero Shadow Days, measure altitude, and track the positions of certain stars and the time of sunrise and sunset.

Also read: Saris, kumkum, gossip—Women are central to Thota Vaikuntam’s art

Mahabharata’s military strategies

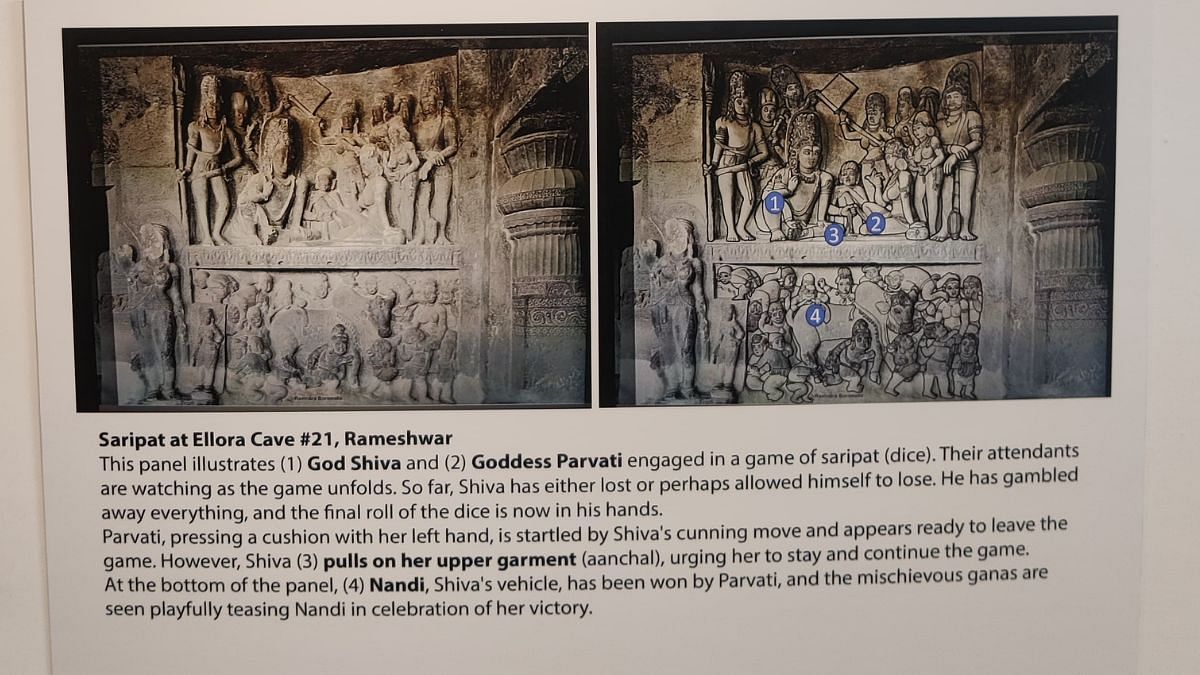

The Ellora Caves, carved from tough Deccan trap rock around the seventh century, have seen both beauty and destruction and tell a story of art and strength.

Among many tales carved in the Ellora Caves, one stands out the most with the dramatic encounter between Ravana and Kailash Mountain. As per mythology, in his quest for Shiva’s blessings, Ravana, consumed by anger, attempted to uproot the mighty mountain. However, Shiva intervened with a serene gesture, effortlessly stabilising Kailash with his toe. As a result, Ravana composed the Tândav-Stotra, a devotional hymn expressing his respect and admiration for Shiva.

The carving was defaced over the years, it now exists as a worn version of the original art.

“Like the Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia, which has images of its original form for visitors to compare, we hope to secure sponsorship to bring back the caves’ lost beauty,” Apte told ThePrint, discussing a project that aims to regenerate what has been lost and distorted by Muslim conquerors.

This project mirrors the efforts made at Angkor Wat, where visitors can view an album showcasing the original temple alongside its current state.

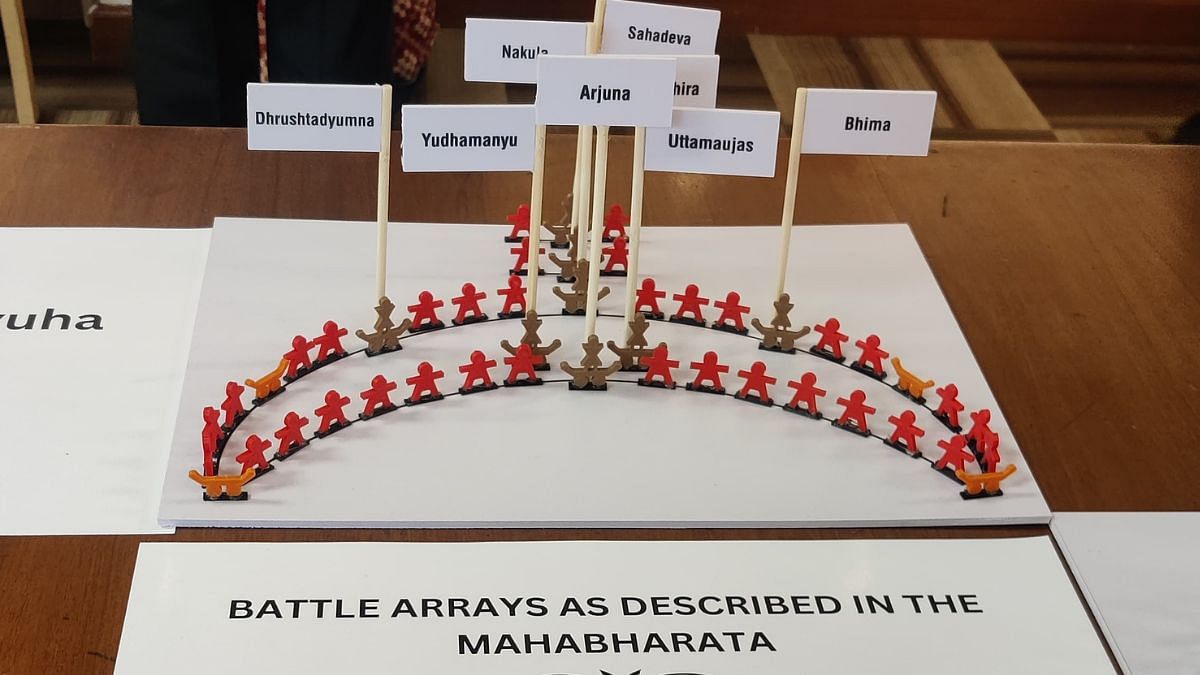

In addition to the artistic heritage of the Ellora Caves, BORI is committed to exploring the richness of ancient texts, including the study of military strategies depicted in Mahabharata. Among the manuscripts housed at BORI, scholars have examined the intricate descriptions of battle arrays, particularly the Ardha Chandra Vyuha and the Vajra Vyuha formations. The Ardha Chandra Vyuha, known for its crescent shape, and the Vajra Vyuha, recognised for its diamond-like structure, are significant for their symbolic and tactical implications in the epic’s narratives.

The exhibition showcased these formations, illustrating how scholars have reinterpreted ancient manuscripts to bring these military strategies to life.

Cultural sensitivities and academic interests

In 2004, BORI found itself at the centre of a tragic incident that revealed the fragility of cultural institutions amid rising tensions around historical narratives. The vandalism was incited by a book written by American author James Laine, who was accused of sensationalising the life of Maratha King Chhatrapati Shivaji, a revered figure in Maharashtra. Laine’s book sparked outrage among Shivaji’s supporters, leading to an attack on BORI.

“Because he associated himself with BORI, we had to bear the brunt,” Apte told ThePrint.

The incident was more than an isolated event; it highlighted the delicate balance cultural institutions must strike between preserving knowledge and respecting deeply held beliefs.

“Tensions are an inevitable part of academic discourse because society does not share a uniform perspective. Historical interpretations can provoke strong emotions, particularly when they concern figures of cultural significance,” said Apte.

Over the decades, BORI has encountered and dealt with various intellectual and conservation challenges. The dwindling demand for ancient languages such as Sanskrit and Prakrit is leaving prospective scholars with limited job opportunities. Workshops are conducted regularly, but the allure of immediate job prospects often overshadows the cultural significance of these studies.

“The academic landscape is increasingly skewed, prioritising financially rewarding subjects over those that preserve our identity and heritage,” Apte told ThePrint, adding that despite a growing interest in ancient knowledge—driven by technological advancements and increased awareness—many still pursue these studies merely as hobbies.

“Our digital platform offers video lectures that have become immensely popular,” said Apte. “We’ve even held customised versions of our lectures on the Mahabharata for universities across the globe, adjusting to different time zones to reach a wider audience.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Dear Ms Mehra.

Two errors stand out. Ellora caves were carved during seventh century, not seven centuries ago. Second, Author James Laine who wrote the book on Shivaji is an American rather European. You also called him James Clay. These kind of errors make me suspect that there may be several more factual inaccuracies in your report.

I hope in the future you will take greater care in your reporting.

Thanks

. Jonathan Sammy