New Delhi: At Sunder Nursery, under the warm spring sun, Bengal’s textile heritage took center stage with the launch of Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy.

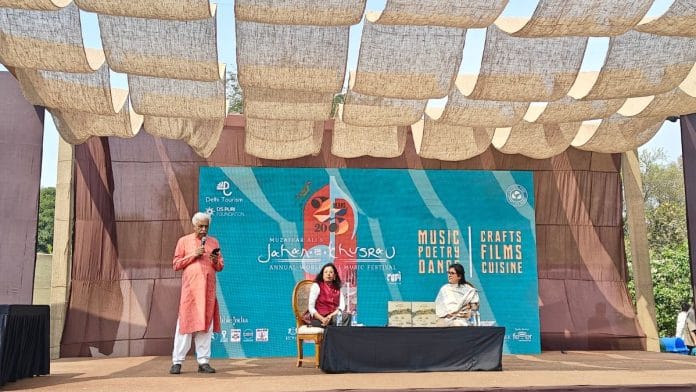

Held as part of Muzaffar Ali’s Jahan-e-Khusrau World Sufi Music Festival, the event was a convergence of scholars, designers, and textile enthusiasts eager to know the weaves of history.

Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy is no mere documentation—it is a deep dive into craft, colonialism, and resilience. Through rare archival visuals and meticulous research, it brings together the grandiosity of Bengal’s weaving traditions while confronting the difficulties brought by colonial trade.

The book is a call to action. In an era of mass production, the book reminds readers that the survival of Bengal’s textile legacy hinges on sustainable interventions and cultural appreciation. As Darshan Shah, Founder–Trustee of Weavers Studio Resource Centre and contributor to the book poignantly put it, “If we do not acknowledge the hands that weave our past into our present, we risk unraveling a history that defines us.”

Ritu Sethi, Founder Trustee of the Craft Revival Trust and one of the contributors to the book said the work has filled a huge gap. “It’s astonishing that a tradition so ancient, in a land once globally and locally renowned for its textiles, has only now, in 2025, received a book that delves into it so deeply.”

Darshan Shah, Founder–Trustee of Weavers Studio Resource Centre and contributor to the book, was also present at the event.

She spoke about a field visit to Naupada and Kalna, where she encountered a Jamdani weaver immersed in his craft. What struck Shah was the absence of any structured checks, graphs, or design sheets—yet, the patterns emerged flawless, as if woven straight from memory. When she asked the weaver about his process, he responded not in words but in song—what the author describes as a “mathematical song”, where calculations and patterns were encoded in rhythm.

The oral tradition of weaving songs extends beyond the looms, according to Chandra Mukhopadhyay, independent collector and researcher of women’s folksongs of Bengal.

“Eager to get acquainted with the voices of the rural women of Bengal, I started collecting these songs from different villages and refugee (erstwhile East Bengal) colonies from all over West Bengal, and the Bengali-speaking areas of Assam, including Goalpara, Silchar, and Karimganj,” Mukhopadhyay writes in the book. These songs, carrying histories of displacement and resilience, form an undocumented yet essential part of Bengal’s textile legacy.

Also read: How images from US spy satellites are helping map Bodh Gaya’s sacred landscape

India’s textile heritage

Beyond nostalgia, the book raises urgent questions. It highlights how Bengal’s textile industry, once the heartbeat of the region, now grapples with modern challenges—industrialisation, dwindling patronage, and policy neglect. Women, often the invisible custodians of these traditions, continue to preserve their craft despite economic uncertainties.

“Their hands hold centuries of knowledge, yet their struggles remain invisible in policy discussions,” Darshan Shah noted in the book.

Ritu Sethi pointed to a larger trend in the country—an awakening to India’s textile heritage. “We have 95 per cent of the handlooms in the world, and all couture hand embroidery originates from India.”

We are becoming so conscious of our art, and what we are wearing, that we are going back to these remarkable skills and traditions. Sethi said it’s a “point of intersection” where machine-made garments flood urban markets, yet a revivalist energy surges among artisans and designers alike to celebrate India’s rich textiles.

The discussion veered toward contemporary fashion. Bengal’s handloom legacy is not just confined to museum displays; it breathes through collections by designers such as Sabyasachi Mukherjee, Rajesh Pratap Singh, and Payal Pratap.

“For the last 15 to 20 years, contemporary designers have been turning to Bengal for inspiration,” Darshan said, emphasising how jamdani, muslin, and kantha embroidery now command global attention. Bengal’s textiles blend well with fabrics from other regions, such as Gujarat’s, creating unique combinations in contemporary fashion.

The book’s research was not without hurdles. Archival accuracy, sourcing reliable references, and delays from international contributors posed constant challenges. The launch itself was an intimate affair—not a packed house, but a deeply engaged audience. “It was a small turnout, but those who came were deeply engaged, and people were truly interested in understanding the deeper history of Bengal’s textiles,” Darshan said.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)