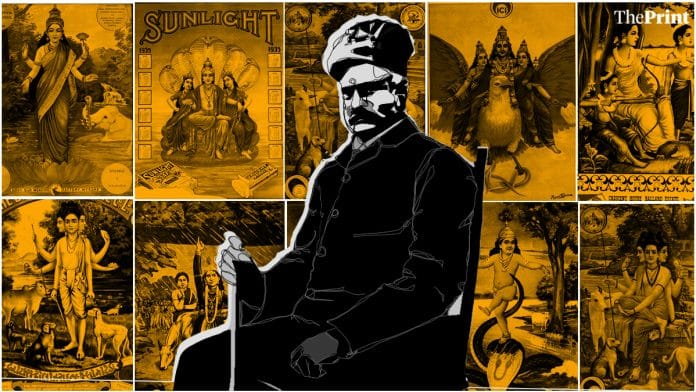

New Delhi: Raja Ravi Varma revolutionised art by blending the divine with the mundane, challenging traditional norms. Accused of diluting the purity of deities, the 19th-century artist faced criticism from the upper class and a court case was filed against him in Mumbai. But he remained steadfast in defending his vision and ultimately won the case, securing a victory for artistic freedom in India.

“When an artist dares to break barriers, negativity and opposition are inevitable,” said Rama Varma Thampuran, a musician and the descendant of Raja Ravi Varma at an exhibition celebrating the art of Raja Ravi Varma and his disciple MV Dhurandhar.

“Ravi Varma stood firm, proving that art can both honour tradition and push boundaries.”

Recently inaugurated at the Transport Museum in Gurugram and on display till 31 March, Prints of the Divine brought together over a hundred rare oleographs, lithographic plates, and postcards. As the visitors explored the intricately curated displays, they whispered about their favourite works, shared stories of growing up with Varma’s art in their homes, and marvelled at the timeless appeal of Dhurandhar’s depictions of colonial Bombay. Raja Ravi Varma’s art wasn’t just about mythologies; it was a quiet revolution, turning age-old epics into everyday conversations for an emerging modern India.

“Raja Ravi Varma democratised art long before anyone else even thought of it. His work broke through class barriers. Suddenly, a farmer in a village could have a piece of Ravi Varma in his home, worshipping Saraswati or Lakshmi as painted by the master,” Prem Kandwal, curator of the exhibition told ThePrint.

The divine painter legacy

Before his first major painting, Raja Ravi Varma’s elders told him to seek the blessings of Mookambika Devi. This goddess is Lakshmi in the morning, Durga in the afternoon, and Saraswati in the evening. Varma walked for seven days through jungles, fasting, to worship her. On his way back, he received his first commission—to paint for a judge.

“Imagine a man with no transport, journeying through dense forests, driven purely by faith. I believe it was divine intervention that guided him, just as I feel guided in my mission to showcase his legacy,” said Kandwal.

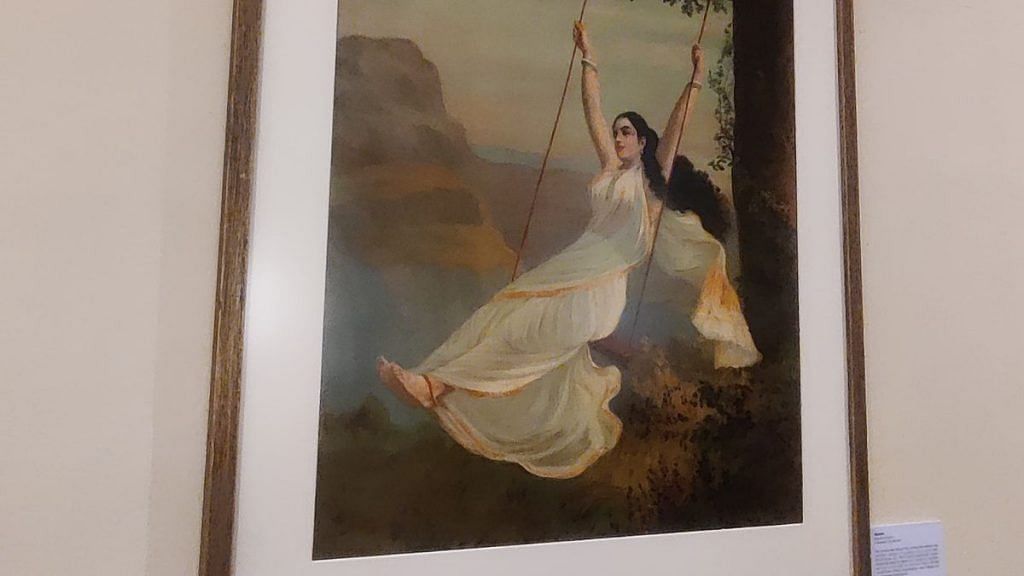

Raja Ravi Varma’s brilliance lies in his ability to merge Indian iconography with European academic realism, creating timeless masterpieces that resonate with emotional depth. Among the highlights of the exhibition is his painting Sita Vanvas (Sita in Exile), which captures the moment of Sita’s second exile in the forest. Draped in a flowing mustard-yellow sari, her sorrowful gaze speaks volumes of despair and quiet resilience, while the tranquil landscape behind her deepens the narrative’s emotional pull.

One of the most captivating showcases is a collection of postcards procured from France by Kandwal, showcasing prints of Varma’s works. These postcards tell the story of how the artist’s lithographic prints became a cultural phenomenon. By mass-producing images of Hindu deities and distributing them across colonial India, Varma made art accessible to everyone—from the elite to the commoner.

Kandwal’s grandfather and father, Maha Nand Kandwal and Kanta Prasad Kandwal began the collection of genuine oleographs around 1910-12, sourcing items that are now nearly impossible to find. To expand the collection, Kandwal acquired pieces from auctions in London, galleries in France, and Indian families who had emigrated to Singapore. “The British took so much of our heritage, and now their descendants sell it in European markets. Even postcards are rare in India,” he said.

Ravi Varma’s art was, and continues to be, a bridge between India’s past and its aspirations for the future, Kandwal stressed. “His work was not just about painting but about shaping a new identity for India.”

Also read:

Democratisation of art

Raja Ravi Varma was not always an artist for the masses. His talent and vision were revered, with his art initially finding its place in the grand halls of princely estates, commissioned by maharajas and nawabs. Yet, there was an innate desire in him to bring his art to the ordinary household—to penetrate the lives of middle and upper-middle-class families. This aspiration led to the founding of the Raja Ravi Varma Press in 1894 in Mumbai. Here, he created his first oleograph, Shakuntala Janam, which became the central theme of Kandwal’s exhibition.

“He wanted his art to reach every home. His oleographs were groundbreaking, but they weren’t cheap. Initially, these prints were expensive, accessible only to the affluent. It was only after 1930, with industrialisation, that they became affordable for the masses,” said Kandwal.

The exhibition explored the contrasts between Varma and his contemporary, Dhurandhar. While Ravi Varma painted for royalty, Dhurandhar’s art celebrated commoners. He sketched barbers, and everyday life during Bombay’s industrial revolution. Both artists had their own space, their own magic.

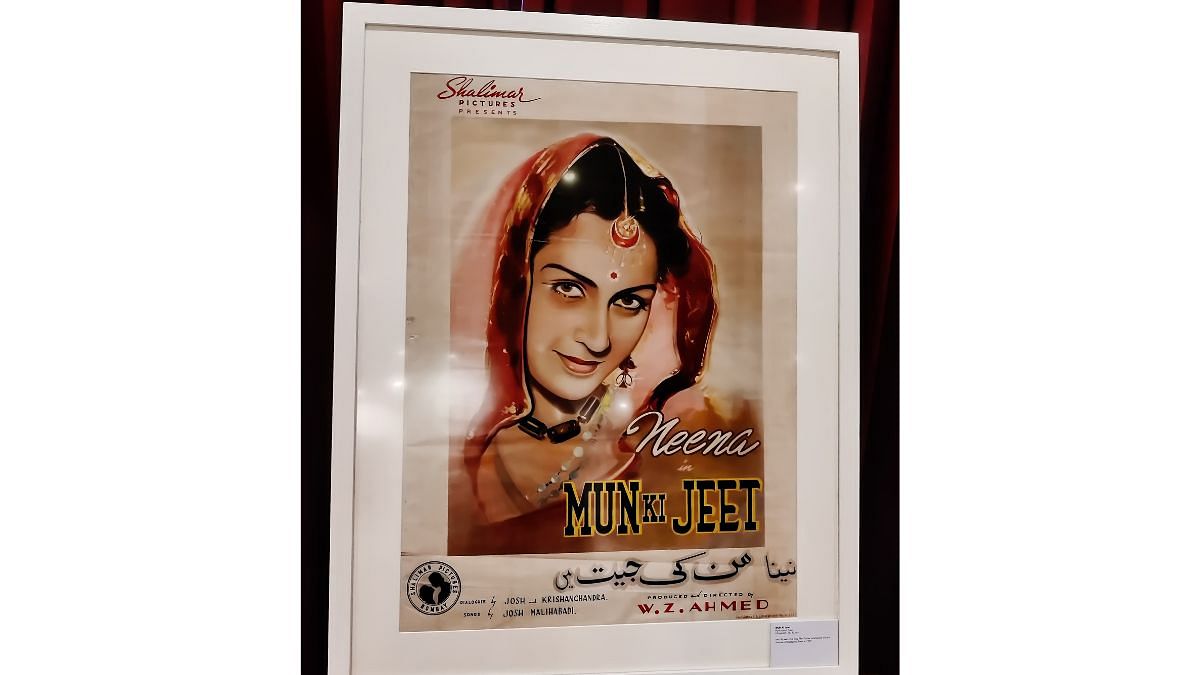

Dadasaheb Phalke, a disciple of Dhurandhar and an apprentice at the press, drew heavily on his postcards when staging scenes for Raja Harishchandra (1913), India’s first feature film.

“The narrative clarity of Dhurandhar’s postcards laid the foundation for early Indian filmmaking,” said Kandwal. His ability to capture movement, emotion, and atmosphere translated seamlessly into cinematic storytelling.

Ravi Varma’s struggles, be it the criticism, the financial troubles of his printing press, or the loss of his brother, never deterred him from his mission to democratise art. “He believed that art was for everyone, not just the elite. His life is a testament to the power of passion and perseverance,” said Rama Varma Thampuran.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

Raja Ravi Varma died in 1906. How could he design a poster of a film released in 1944