Bengaluru: South Indian literature has a rich cultural history spanning 2,500 years. Yet, throughout this time period, it has grappled with challenges related to access, translation, and equal representation in the competitive literary world. But when over 300 renowned South Indian language writers—in Kannada, Malayalam, Telugu, and Tamil—gathered in Bengaluru last week, their foe as of 2024 was Artificial Intelligence and the new wave of ‘mindless translations’.

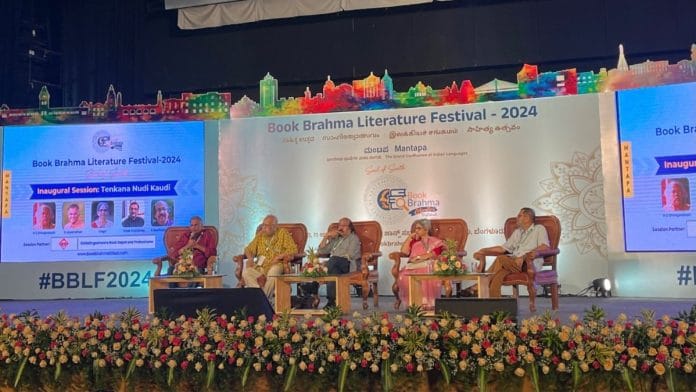

It was one of the central themes at the first-ever Book Brahma Literature Festival: Soul of South, which kicked off on 9 August. South Indian authors including Perumal Murugan, Jayant Kaikini, B Jeyamohan, and HS Shivaprakash, among others, were part of the three-day festival that had more than 80 panel discussions, performances, and exhibitions. Its USP is that it is solely dedicated to South Indian languages.

The festival proved to be the perfect platform for authors, editors, publishers, and readers to discuss how sloppy AI translations are perpetuating biases and prejudices, while stripping works of context.

Kannada folklorist and fiction writer Krishnamurthy Hanur drove this point home by discussing the strong relationship between the poet and his surroundings, at a session titled, ‘Age of AI—The End of the Classics’.

“AI cannot recreate that,” said Hanur, recalling an instance when an excerpt from Kuvempu’s novel Malegalalli Madumagalu was fed into an AI platform with the intention of turning it into a play.

But the result didn’t have the human and emotional touch, Hanur added.

Kannada poet and author Poornima Malagimani, who too was on the panel, spoke about how nuances are lost in translation.

“There are so many small nuances in languages,” she said adding that not all of them are conveyed through speech.

“People speak through body language and expressions, like the silent conversation between a pedestrian hailing an auto and the driver stopping to attend to them. “How can AI ever convey this?” Malagimani asked.

Also read: Mirza Ghalib returns. Uses Instagram, attends Ambani wedding, told to ‘go to Pakistan’

Lost in translation

With AI taking over, there are fears that the ‘human touch’ will quietly disappear from translated works. After all, translators are interlocutors who bridge the gap between different languages and cultures.

“Finding someone who can do this across languages has become increasingly difficult,” said Akhil Mehta, managing director of the Pune-based Mehta Publishing House, a powerhouse in the Marathi publishing industry.

In a discussion on ‘The Challenges of Publishing from English to Indian Languages’, Mehta underscored the ‘essence’ of the original text, and the need to maintain it in the translated work as well.

It is one of the core responsibilities of a translator, he said.

For the most part, writers rely on educational universities for bilingual translations. And according to the panellists, there are very few translators who are driven by the sheer passion for language.

Similar issues were raised in another session, ‘The New Wave of Translations into Telugu’, where Telugu writer Kathyayani was critical of the recent wave of young urban translators who are born and brought up in cities. Her conclusion? Their Telugu translations are more colloquial than informative and effective.

“Their cultural environment is different, hence their translation resembles the language style of a radio jockey or a movie scene,” she said.

Not everyone approved of the influence of pop culture on translations, and the erosion of gravitas.

This is where the challenge lies. It isn’t merely about finding someone who understands more than one language; it is more about finding someone who can preserve the cultural and emotional nuances embedded in the original text, said Mehta.

And while there’s always demand for skilled translators, the profession still doesn’t pay much — given the value they bring to the table.

For software engineer, writer, and translator Purnima Tammireddy, translating Saadat Hasan Manto’s Urdu works on Partition into Telugu, was a way of making sense of the communal and political riots that she witnessed in Hyderabad as a child.

“I always wondered why people kill each other and why should a human be scared of another from their own race,” Tammireddy recalled. She searched for the answers in history books across multiple libraries.

“I realised then that if we translated Manto’s work in the context of previous political developments, it would then make for an interesting read,” she said.

Her translated work, ‘Siya Hashiye’ or ‘Vibhajana naati Nettuti Gayaalu’ in Telugu, isn’t just a collection of translated works of Manto and other partition stories, but a commentary on current political developments in relation with Partition stories.

“It wasn’t just a mechanical and mindless translation which is becoming common these days,” she said.

Also read: Jharkhand’s coalfields to plight of migrant workers—exhibition displays beauty amid chaos

Emerging trends

Every literary festival after interrogating the past looks to the future to identify new trends. And in keeping with the current fascination for India’s epics, there’s a renewed demand for this in the regional literary world as well.

But readers want fresh interpretations of iconic characters from Indian epics in regional languages. For example, Malayalam classical poet Kumaran Asan’s Pensive Sita, loosely translated as Sita’s Musings, sees Sita as an assertive and independent woman.

Readers are leaning toward classics that reflect their hyperlocal realities. So, Abhaya Simha, a two-time National Film Award winning filmmaker, decided to re-examine Shakespeare’s Macbeth in a modern setting and in Tulu, a language mainly spoken in the southwest part of Karnataka.

The movie, Paddayi, meaning ‘west’ in Tulu, plays out in a tiny coastal Karnataka village. The characters, belonging to an indigenous community of fishermen, try to navigate new challenges of modernisation in fishing practices.

In the backdrop of growing rumblings against what authors and guests said was the increasing imposition of Hindi, literary works in Malayalam, Kannada, Telugu and Tamil literature continue to thrive. But it’s not enough–more writers, poets and translators to spread their word are needed.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

I thought their main enemy was Narendra Damodardas Modi.