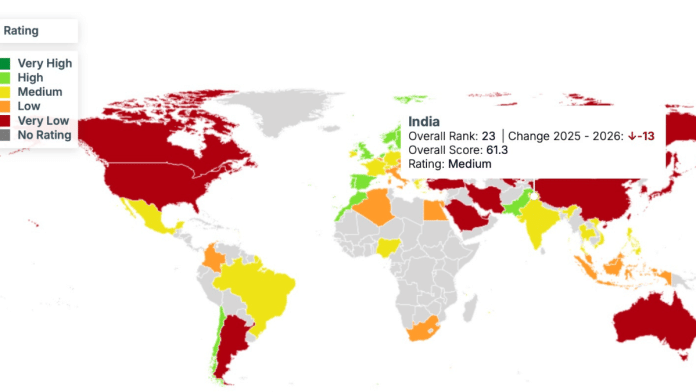

Belém (Brazil): India’s performance in tackling climate change declined significantly over the past year, with the country sliding 13 spots in the Climate Change Performance Index 2026 released here at the COP30.

India is ranked 23 this year in the index that tracked 63 countries and the European Union’s climate mitigation performance on four parameters—greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energy, energy use, and climate policy. In 2025, India was ranked 10.

“India has serious constraints in phasing out/phasing down coal, and these cannot be solved overnight,” D. Raghunandan, the founder-member of Delhi Science Forum think tank, told ThePrint. He noted a shortage of investments in solar and wind energy, weak electricity transmission capacity, lack of adequate storage, and poor grid stability as major issues driving India’s reliance on coal.

India performed ‘medium’ in all categories except renewable energy, in which its performance has been measured as ‘low’. Similar to last year, the top three spots remain unoccupied this time as well, with the ‘first’ position—the fourth spot in the index — claimed by Denmark.

Published annually since 2005 by Germanwatch, NewClimate Institute, and the Climate Action Network, the CCPI 2026 report noted India’s “long-term intent on climate action”, but said that its dependence on coal remains an obstacle.

“The national pathway is still anchored in coal. There is no national coal exit timeline and new coal blocks continue to be auctioned,” the report’s note on India read.

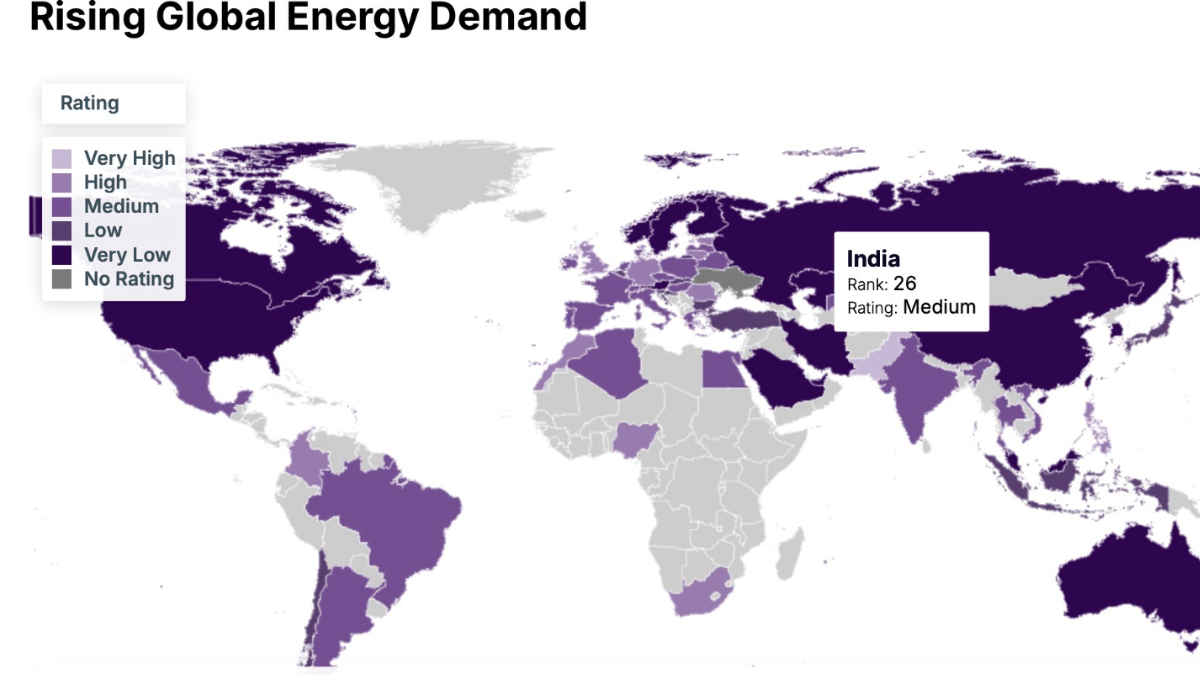

The 63 countries and the EU together account for more than 90 per cent of global GHG emissions. Between 2015 and 2023, the total primary energy supply per capita also recorded an increase, with China (28.8 per cent), India (22.7 per cent), and Vietnam (50.8 per cent) registering the maximum rise in energy use.

Also Read: India’s NDCs by Dec, Bhupender Yadav tells developed nations at COP30 to speed up net-zero targets

India’s impediments

India’s renewable energy push has garnered significant attention and applause. The 2026 index report noted “substantial progress”, with India achieving a 13.9 per cent share of renewables in its total energy mix from 2015 to 2023, which the report said, is well above the global average. However, the renewable energy push is not without its challenges. India’s large grid-scale renewable projects have triggered land conflicts, displacement, and water stress.

“This is a serious problem. Local protests are growing all over the country, including in sparsely populated and solar-rich Ladakh. It shows lack of thoughtful planning, participatory decision-making, and forcible implementation,” said Raghunandan.

He also dismissed the argument that land conflicts are “inevitable” when scaling clean energy in a country as densely populated as India.

“The ‘inevitable’ argument is a convenient excuse for lazy and non-participatory governance. One has very rarely seen examples of the government examining and presenting analysis of different alternatives before deciding on a particular project,” Raghunandan said, adding that these conflicts are the result of “a huge governance failure.”

According to climate and water expert Ranjan Panda, who is the convener of the Combat Climate Change Network, land and water conflicts are part of any major development process.

“This is why I strongly advocate for co-ownership. In this model, people are not stripped of rights over local resources, investors provide capital and technology, and the government regulates to prevent dispossession and exploitation,” he told ThePrint.

Climate equity, historical injustice

Although India’s coal dependence and renewable energy challenges shaped much of this year’s assessment, experts say the country’s lower ranking must also be viewed through the long-running debate on climate equity.

Several developing countries, including India, argue that global indices tend to highlight present-day emissions while underplaying the historical responsibility of the developed world—a framing that, they say, places disproportionate scrutiny on emerging economies even as the US and parts of Europe “revive coal and delay harder cuts”.

Raghunandan echoed this concern, saying the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI)’s emphasis on future and current emissions overlooks how industrialised nations have “overdrawn” on what remains of the global carbon budget.

“There is too much emphasis on reducing fossil fuels in developing countries, while even the US and parts of the EU are reviving coal,” he said. “The focus on present and future emissions, without accounting for historical over-consumption of the carbon budget, is a very inequitable perspective.”

While Panda refrained from commenting directly on how CCPI weighs developmental equity, he too underscored that India’s transition will only be meaningful if it delivers social and economic gains to the people who stand to be most affected.

“Working alone on technology by fixing big targets is not going to help in promoting inclusive growth. We have to think about models that don’t just benefit a few investors or project proponents,” he said.

Experts say the next phase of India’s climate effort will depend on whether it can build a transition framework that is fair and locally grounded. Panda said this will require stronger safeguards and a shift in how projects are planned.

“India should accelerate the process of working on a Just Transition Framework that’s inclusive in all senses,” he said. “Projects should not see people just as subjects who can be moved at the will of the project proponents.”

Raghunandan added that global responsibilities will remain central to what India can and cannot do. He criticised the global community for not putting enough pressure on developed countries to reduce emissions sharply, arguing that the world instead seeks scapegoats in India and China.

“Even India is to blame for this, as it doesn’t put more pressure on the US and EU. India should say, ‘we are ready to cut emissions more if you cut emissions more deeply to enable 1.5°C’.” he said.

(Edited by Ajeet Tiwari)

Also Read: Oil’s not well: 1,600 fossil fuel lobbyists attending COP30 in Brazil, says climate advocacy group