New Delhi: As India reels under pressure from the Trump administration’s tariffs, some industry representatives warn that quality control orders (QCOs)—meant to enhance quality of domestic product while restricting substandard imports—are increasingly being used as an instrument of “protectionism” rather than improving “quality”.

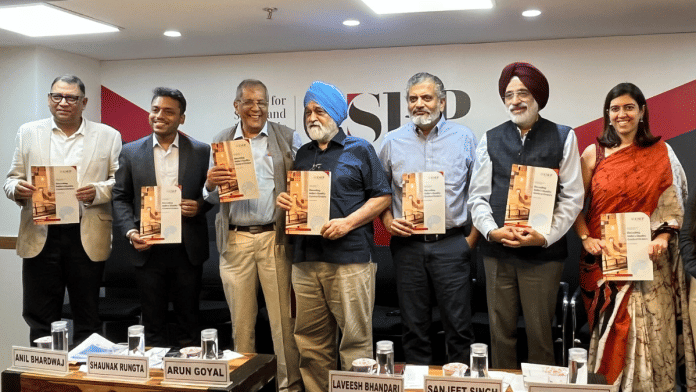

Speaking at a panel discussion on ‘Decoding India’s Quality Control Orders’, at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP), on Tuesday, they also said QCOs have effectively become non-tariff barriers, adding another layer of compliance burden and cost on Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises (MSMEs).

Governed by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) and issued by the government, QCOs aim to improve the quality of domestic products while restricting the import of substandard products. Once a QCO comes into effect, no one can manufacture, import or sell the product covered by the order without having a BIS standard mark under a valid licence.

QCOs are governed by the BIS Act, 2016, but they have been used excessively by the government after 2019 to reduce reliance on imports and promote self-reliance in manufacturing for both domestic and foreign markets.

There were 88 QCOs in 2019; by December 2024, the number jumped to 765, according to a CSEP working paper. Metals, machinery and electronics account for more than 60 percent of QCOs between 1987 and 2025.

“QCOs are not about quality; it is being incessantly used as a protectionist measure to protect a few large industry players,” Shaunak Rungta, director of stainless steel manufacturer Vardhan Group, said at the event.

Citing an example what he called disproportionate burden on MSMEs, Rungta said the BIS mandates a bank guarantee of $10,000 per product. For a small manufacturer with an annual turnover of just $1.15 million (about Rs 10 crore) producing 30 products, that works out to an unaffordable $300,000.

“There cannot be a blanket rule for everything, as one size cannot fit all,” he added.

According to Sanjeet Singh, a panelist and senior advisor to the Niti Aayog, QCO compliance has increased certification and administrative costs for MSMEs. “Compliance should not consolidate market power in the hands of a few; rather, it should foster competition,” Singh said.

Another panelist, Academy of Business Studies Director Arun Goyal, told ThePrint that the true beneficiaries of non-trade barriers like QCOs are vested monopolies. “QCO measures are meant to protect the consumer, but in turn, they are promoting a monopoly.”

According to Niti Aayog’s Singh, the feedback from MSME players is that QCOs are creating supply chain bottlenecks due to delays in testing and certification of intermediate products, which are critical for domestic production.

The impact of QCOs on the import of intermediate goods is highlighted in CSEP’s working paper, which says that QCOs led to a 16 percent drop in imports of intermediate goods in the year of its notification, and a 17.5 percent decline in the subsequent year, while in the long-term, it resulted in a 30 percent decline.

The working paper also highlights that nearly 45.7 percent of all QCOs apply to intermediate goods, followed by 40.5 percent to consumer goods and only 13.8 percent to capital goods.

According to Goyal of the Academy of Business Studies, QCOs must be restricted to end-consumer products only and not applied to raw materials or intermediate goods essential for domestic production.

While QCOs are acting as a barrier for trade flow, they are also bringing back the old “license raj system”, according to Vardhan Group’s Rungta.

He cites several bureaucratic hurdles in obtaining BIS certification, such as visits by inspectors to factories abroad to check the quality and certify the product, which further delay the process by up to seven to eight months.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: Navigating Trump’s tariffs is no child’s play. Indian toymakers are losing out on orders, enquiries