India’s journey toward financial inclusion has witnessed various innovations in policy over the past few decades. In the early 1970s, this meant the pursuit of bank nationalisation and improving the presence of banking services in rural areas.

The advent of Aadhaar in 2009 was a watershed moment, as it marked a paradigm shift in policy — towards the use of technology to drive financial inclusion. Once the foundations of digital infrastructure had been laid, it became more apparent how such infrastructure would be leveraged for the purpose of improving financial inclusion outcomes.

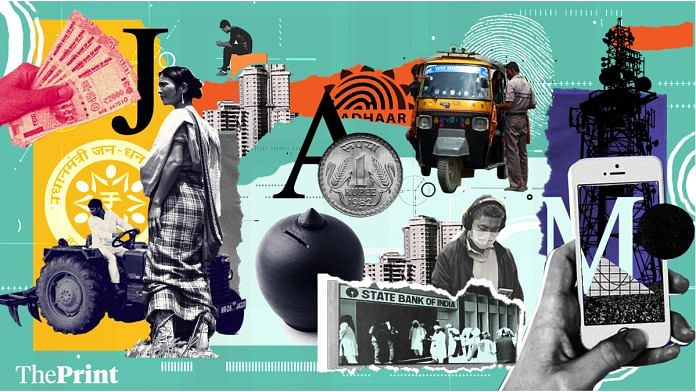

One method of doing so was to use the ‘Jan Dhan Account – Aadhaar – Mobile’, or JAM, trinity to facilitate Direct Benefit Transfers (DBTs) of welfare subsidies into bank accounts of the poor. The driving motivation was to increase account ownership and usage by making government transfers into citizens’ bank accounts. As a result, the market segments typically underserved by the formal financial system could be brought into its fold.

Also read: Inclusive, efficient, accountable — how to make digital welfare platforms more citizen-centric

Components of the JAM trinity

The core components of the JAM architecture are the basic savings bank accounts provided under the Jan Dhan Yojana, the unique biometric identifier in the form of Aadhaar, and the rapidly increasing Mobile penetration in the country. Each of these components has a specific function within the DBT pipeline:

• The Aadhaar number helps identify those who are eligible for various government schemes and confirms their identity through biometrics. Since Aadhaar numbers are mapped to bank accounts, it also acts as an individual’s financial address, allowing ease of electronic welfare payments.

For instance, an individual would submit their Aadhaar details to enroll into the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) or to receive old age pension as per the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme (IGNOAPS). Their identity would be verified against their Aadhaar, and the relevant benefits transferred to the bank account which is linked to the provided Aadhaar number.

• Government transfers are pushed directly into citizens’ Jan Dhan Accounts, which are zero-balance, no-frills savings accounts.

• High mobile ownership ensures outreach and communication to citizens upon successful transfer of the welfare payment.

The JAM trinity has impacted financial inclusion in the following manner:

Improving access to formal finance

One of the important thrusts under JAM was to improve bank account ownership by bringing banking to the bottom of the pyramid. By government estimates, approximately 470 million individuals hold Jan Dhan bank accounts, opened since 2014, of which 261 million are women account holders.

The initial offer of Jan Dhan accounts was bundled together with the RuPay debit card and government-provided pension and insurance schemes. This bundling helped improve access to a variety of financial instruments for the bottom of the pyramid.

While account ownership has indeed increased significantly over the past few years, whether this has translated into meaningful financial inclusion remains to be seen. Approximately 14 per cent of all Jan Dhan accounts were inoperative as of August 2021. From our field interactions with beneficiaries, we have learned that many account holders were unaware of the terms/conditions and benefits of holding a Jan Dhan account. Accounts were often opened hastily to help meet targets, ignoring the customer’s need to be provided adequate information.

The outcomes of such a drive include duplication of Jan Dhan accounts (the same person holding multiple accounts) and improper know-your-customer (KYC) protocols. Our past work has also demonstrated that low-income customers are often actively discouraged and misinformed about basic savings products (such as the Jan Dhan account). Given questionable implementation practices and low levels of awareness, true financial inclusion does not seem to have been achieved.

Facilitating Direct Benefit Transfers

Further, as a key enabler of the DBT system, the JAM trinity has aided improvements in the delivery of government benefits to citizens.

In the past, cash transfers were made through physical distribution channels, which often suffered from leakages through middlemen. The physical distribution of cash was expensive for the exchequer, as well as ineffective for the recipient. The DBT system eliminated physical cash distribution channels, instead facilitating electronic transfers directly into bank accounts. The Aadhaar-seeding of bank accounts allowed for the identity verification of beneficiaries, helping ascertain whether welfare benefits were being sent to the correct individuals.

Theoretically, the use of JAM should create an airtight transfer system with no scope for leakage. This has not played out. For instance, thousands of crores of rupees intended to provide income support to farmers under the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM KISAN) have been siphoned away from deserving beneficiaries into the accounts of ineligible fraudsters.

The DBT system itself is not without fault — our extensive fieldwork has shown that the system tends to exclude the most marginalised.

A prominent concern is that of accessibility of cash-out points — just over 50 per cent of respondents in the Dvara-Haqdarshak survey on exclusion in government-to-person payments reported that cash-out points were too far away from them. Digital transfer of welfare benefits is not useful without supporting physical infrastructure to allow citizens to withdraw benefits into cash.

The JAM trinity has, to a certain extent, moved the needle on financial inclusion. However, some teething issues must be addressed before the programme realises its true potential.

Aishwarya Narayan is a Research Associate at Dvara Research

The article is part of our series of financial explainers in partnership with Dvara Research.

Views are personal.

Also read: Can financial decisions be free of emotion? Why it’s not the case in Indian households