Widespread feeling at IMF meeting was that ground under global economy, financial markets and multilateral trading system has started to shift.

Washington: Woken one night by a 6.4 magnitude earthquake at the IMF annual meetings in Bali, global finance chiefs spent the week assessing the tremors now rippling through the world economy.

The quake “was symbolic for the widespread feeling among participants that the ground under the global economy, financial markets and the multilateral trading system has started to shift,” Joachim Fels, global economic adviser at Pacific Investment Management Co., said as he left the Indonesian resort.

With a stormier growth outlook and wobbly stock markets, finance ministers and central bankers on the island had plenty to talk about. Indonesian President Joko Widodo went as far as to warn “Winter is coming.”

Here are some of the key things we learned:

Market turbulence

Most sounded calm about the recent market turmoil and not readying to ride to the rescue, but then policy-makers don’t have a great track record predicting slumps.

US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said the stock sell-off wasn’t “particularly surprising,” while insisting US economic fundamentals remain strong.

Back in Washington, President Donald Trump blamed the “loco” Federal Reserve’s interest-rate hikes as the driving factor, but fellow central bankers in Bali defended Chairman Jerome Powell.

IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde noted that US stock valuations have been “extremely high,” implying a correction was overdue.

Policymakers also addressed the risks of another financial crisis, a decade after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. “Financial imbalances continue to build up, and the new financial system has yet to be tested,” said Tobias Adrian, head of the IMF’s monetary and capital-markets department.

The message overall was that the world economy is plateauing and by 2020 may be considerably weaker, something for investors to bear in mind.

“Is the sweet spot turning sour next year? More likely yes than not,” said Jerome Jean Haegeli, group chief economist at Swiss Re Institute. “We are very late in the economic cycle.”

Trade drag

Finance chiefs hammered home the message that simmering trade tensions are already denting global growth and need to be resolved. Lagarde was especially blunt in an interview with Bloomberg Television: “Our message was very clear: de-escalate the tensions.”

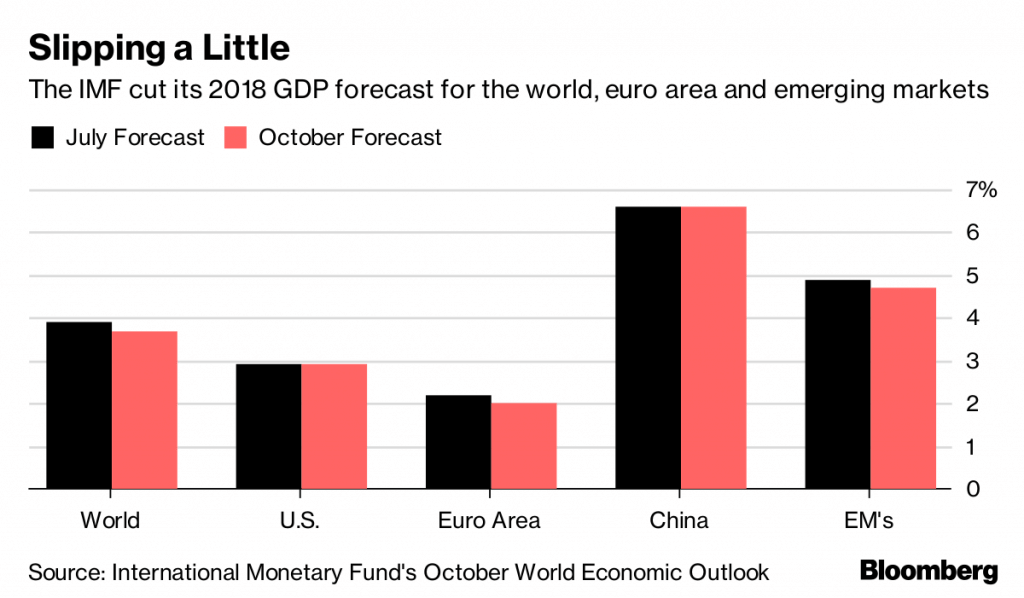

The IMF cited the tensions in cutting its outlook for global growth, noting that some of the risks from higher tariffs have started to materialize. The fund estimates a full-blown trade war would shave more than 0.8 per cent off global output in 2020.

“There’s really only one discussion that’s happening here, in earnest,” said Robin Brooks, chief economist at the the Institute of International Finance. “And that is basically the intensity of the trade dispute between the US and China and how bad that will get — how prolonged and how pernicious.”

Tightening tantrum

A recurring topic was the impact on emerging markets of those rising US rates and the stronger dollar. Policymakers took pains to differentiate themselves from economies such as Argentina and Turkey, which face idiosyncratic challenges.

Finance officials from Colombia and Mexico pointed to rough times ahead, and even the risk of a full-blown crisis for the unprepared. Indonesia’s central bank vowed to stay “ahead of the curve” on monetary policy as the Fed continues hiking. Meanwhile, Pakistan requested yet another bailout from the fund.

“Headwinds from higher oil prices, Fed interest rate increases and a stronger dollar, and the possibility of an escalation of trade tensions, don’t seem to be issues that will be resolved in three to five months,” Changyong Rhee, director of the Asia and Pacific department at the IMF, said in an interview. “Policy makers need to save ammunition.”

The Fed is aware its policies are impacting emerging markets. Vice Chairman for Supervision Randal Quarles said “the right response is for us to be as predictable, gradual about our policy as we can.”

There was even some clarity on what the exit path will eventually look like for the Bank of Japan. The shift will be first seen in its target rate, Governor Haruhiko Kuroda told Bloomberg.

Yuan value

China’s currency was a topic of discussion just days before the US Treasury Department is scheduled to release a closely watched report on currency manipulation.

While US Treasury staff have advised Mnuchin that China isn’t manipulating the currency, it will remain on a monitoring list because of its significant trade surplus with the US, according to people familiar with the matter. A draft report ratchets up criticism of Beijing for failing to rectify its trade imbalance.

The yuan has fallen more than 6 per cent this year against the dollar, prompting speculation it may fall through the key level of 7 per dollar. People’s Bank of China Governor Yi Gang used the IMF meetings to say the government won’t use its currency as a tool to deal with the trade conflict even as a tariff war with the US intensifies.

Meanwhile a senior IMF official described the yuan as “ broadly in line” with China’s economic fundamentals and the drop reflects the PBOC’s commitment to make the exchange rate more flexible.

Europe risk

The rule-busting budget plans of Italy’s populist government repeatedly cropped up at the meetings. Italian Finance Minister Giovanni Tria, at his IMF debut, had his work cut out trying to reassure colleagues that his country is committed to the euro and will put debt on a downward path.

European Central Bank Governing Council member Francois Villeroy de Galhau, sent an implicit warning to the Italian government, some of whose members have at times called on the ECB to step in to stem the rise in yields on the country’s debt. The ECB’s policy path “doesn’t depend on the fiscal uncertainties that can appear in member states,” he said.

The UK’s haggling with the EU over Britain’s exit was another political talking point. The IMF said it still expects the two sides reach a deal that avoids a “hard Brexit” at the end of March. But UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond said the government was prepared to ramp up spending to cushion against a shock to the economy. –Bloomberg