The pharma industry needs to do a better job of grappling with how success tends to bring out its worst instincts.

The Nobel Prize is one of the world’s top honors for recognizing groundbreaking work in science, diplomacy and other fields. But this year’s awards in medicine and chemistry stand out even in august company.

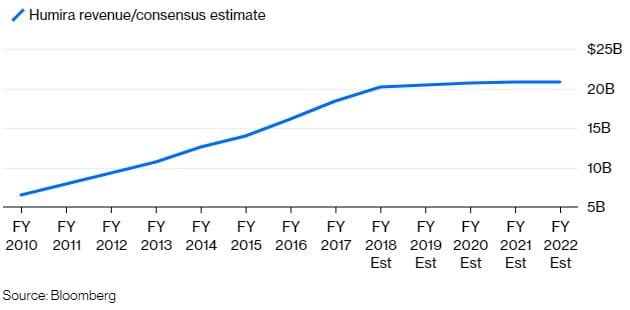

The prize in medicine, given Monday to James Allison and Tasuku Honjo, recognized their research on the immune system, which has led to drugs that have changed the treatment outlook for deadly cancers. On Wednesday, George Smith and Gregory Winter were awarded the chemistry prize for work that helped produce AbbVie Inc.’s Humira, the world’s best-selling drug, as well as a number of other of antibody treatments that have helped improve and extend the lives of millions of patients.

These breakthroughs wouldn’t have been turned into medicines without major investment and risk-taking by the pharmaceutical industry, which is now in line to reap billions in revenue from the treatments.

Of course, drugmakers should expect to reap profit for their efforts — they’re in business to do so. And these medicines represent some of the best possible outcomes of that profit motive. But pharma’s efforts to maximize gains can also work the other way, coloring R&D decisions and creating barriers to entry that ultimately add costs to the health-care system.

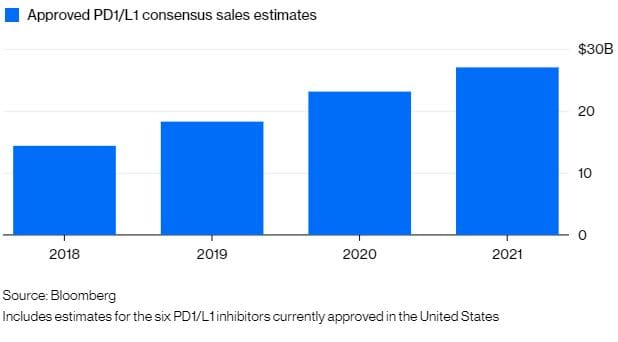

Moneymakers

A class of drugs that this year’s Nobel prize winners in medicine helped bring into the world are expected to generate more than $25 billion in annual sales by 2021

Case in point: There are six marketed drugs in the most successful class of immune-boosting cancer drugs that have emerged from Allison and Honjo’s research. There are many more copycats in development, and firms are working hard to extend the use of these medicines into new populations. Given how lucrative the young market has been — sales of category leader Keytruda, owned by Merck & Co., surged 89 percent in the second quarter from a year earlier — you can see why.

Drugmakers hope that combining these drugs with others will extend their use, as they only help a minority of patients in a few cancers on their own. But the hype over these combos has outpaced results so far, and there have been multiple bruising trial failures already. And while some of the thousands of combo trials currently being run have a compelling scientific underpinning, many others are the product of wishful thinking or are arguably wasteful duplications of effort.

Keytruda and its peers already have list prices of more than $150,000 a year, and combos will substantially boost that price tag — particularly in the U.S., where there’s little pricing pressure on cancer drugs. If combos become widespread, health-care budgets will buckle. And inevitably, over-investment in this one corner of cancer research will result in diminishing returns, and may come at the expense of other efforts.

Drugmakers that market a variety of other aging antibodies have engaged in controversial tactics that stall cheaper copies of their medicines. This isn’t a new set of behaviors in the pharmaceutical industry, but the cost, complexity, and wide use of medicines that owe their existence in part to Winter and Smith’s research have made these delaying actions particularly costly.

These Nobel prizes represent the best of science, and pharma’s ability to translate the discoveries into real-world results is laudable, too. But the industry needs to do a better job of grappling with how success tends to bring out its worst instincts, and regulators need to do a better job of curbing them.