New Delhi: While India’s female Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) has increased since 2017, and quite substantially in rural India, new research has confirmed some commonly accepted facts, such as how some basic aspects of life—advancing age, marriage and having children—significantly and detrimentally impact women’s participation in the workforce.

Notably, the paper also highlights the significant influence of cultural and social norms when it comes to women joining the workforce, with low female LFPRs being seen across rich and poor states alike.

These findings are part of a new working paper, published Friday by the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister (EAC-PM) and authored by EAC-PM member Shamika Ravi and Indian Statistical Institute’s Economics and Planning Unit member Mudit Kapoor.

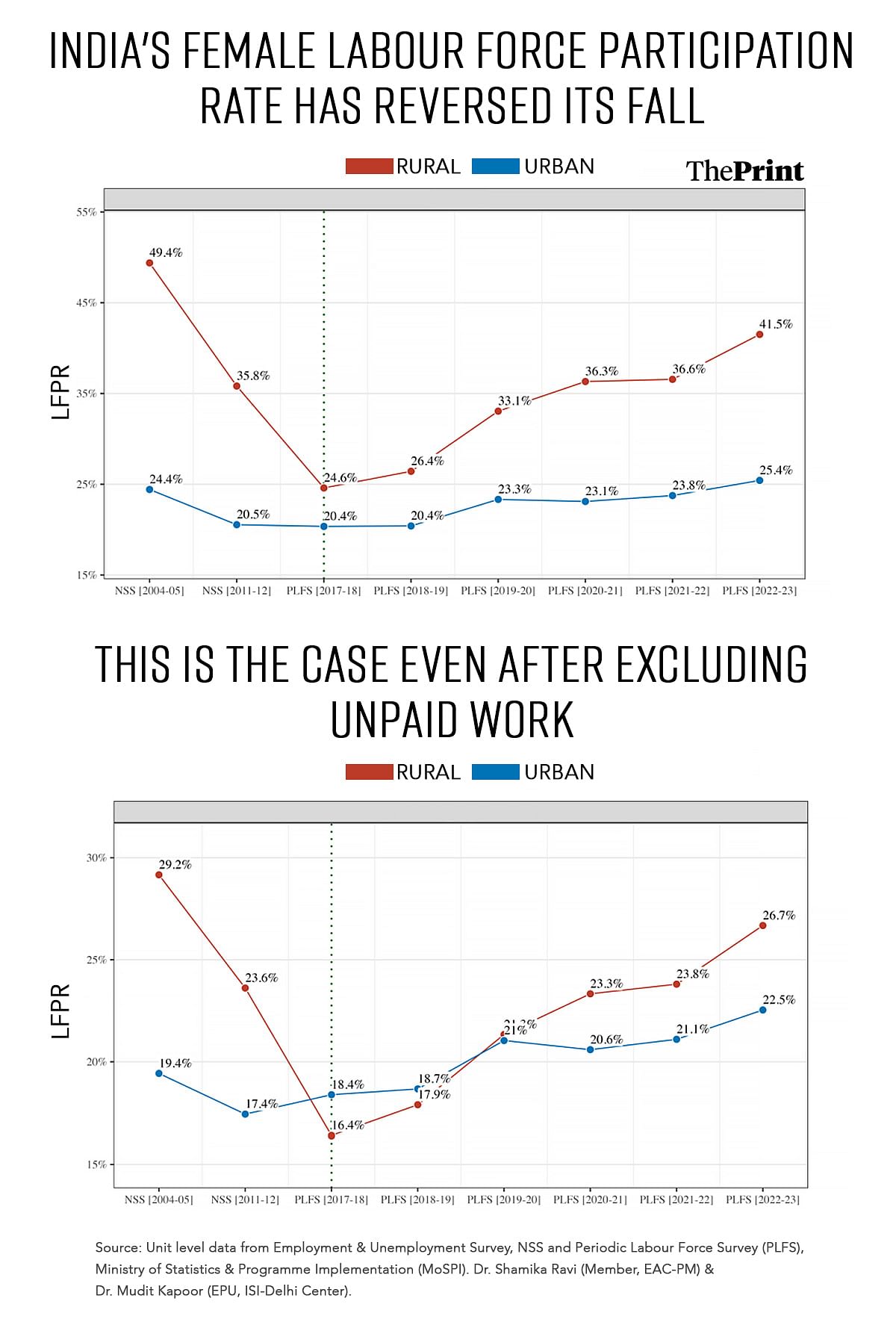

The authors, who analysed the data from the government’s Periodic Labour Force Surveys, found that India’s overall female LFPR “surged” from 24.6 percent to 41.5 percent, while urban female LFPR “rose modestly” from 20.4 percent to 25.4 percent.

Particularly noteworthy is the fact that the authors said the growth in the female LFPR was evident even when removing the segment of unpaid domestic workers. The Opposition has previously attacked the government over this issue, saying that the increase in female LFPR hides the fact that a lot of this work was unpaid.

“In sharp contrast to the period between 2004-05 and 2017-18, where the rural female LFPR declined significantly, the period between 2017-18 and 2022-23 witnessed a dramatic increase in female LFPR, particularly in rural areas,” the paper noted.

It added that previous researchers have attributed this recent increase in female LFPR to a better measurement of unpaid work.

“We explored this and estimated the Female LFPR by excluding unpaid work from the analysis,” the authors said. “The overall trends remain as before. In fact, we find that there has been a consistent rise in female LFPR post 2017-18 (even before the pandemic), and this rise is more pronounced in rural areas than in urban areas across India.”

Also Read: India hits back in WTO over allegations that it supports domestic farmers more than permitted

How life can get in the way of women’s work

One of the observations made by the authors, upon detailed analysis of the disaggregated data, was how advancing age had a different impact on working males and females.

“We also observed that female LFPR typically begins to decline much earlier than male LFPR in terms of age—and this result is consistent across states and areas (rural and urban),” the paper noted. “For example, in most states, female LFPR peaks between 30 and 40 years and then decreases sharply, whereas male LFPR remains flat at nearly 100 percent between 30 and 50 years and begins to decline gradually thereafter.”

In other words, females quit the workforce much earlier than males do. And this has a significant correlation with other aspects of life, such as marriage and having children.

“We observed that currently married women, particularly in urban areas, are significantly less likely to participate in the labour force compared to other cohorts (unmarried and rural women),” the paper said.

It did, however, mention that there were significant interstate variations in these findings. For instance, in Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, the female LFPR does not vary across marital status. Further, in some states such as Rajasthan and Maharashtra, married rural women were more likely to be within the labour force, especially after 40 years of age.

Notably, this trend is the opposite for men.

“Another striking result which is consistent across states and regions of India is that married men are significantly more likely to participate in the labour force than men who are not currently married, and this result is persistent for all ages of men, across all states and areas (rural and urban),” the paper said—another sign of the imbalance in the burden of the domestic workload.

Sometimes society & culture get in the way too

The working paper notes that there are distinct interstate variations in the female LFPR figures, both for rural as well as urban.

“In rural areas, significant increases are seen in states like Jharkhand (around 233 percent growth) and Bihar ( around 6x growth),” the paper noted. “Northeastern states also showed remarkable growth (example, Nagaland: 15.7 percent to 71.1 percent).”

“At the national level, urban areas witnessed modest increases overall. However there is notable growth in urban Gujarat (16.2 percent to 26.4 percent, around 63 percent growth) and marginal changes in urban Tamil Nadu (27.6 percent to 28.8 percent),” it added.

The revelation of this interstate variation, the paper said, was one of its “major contributions” since it highlighted the impact of the socioeconomic, political, and cultural diversity across states in India.

“These diversities play an important role, particularly in determining female LFPR,” the paper noted. “For example, states such as Bihar, Punjab, and Haryana have consistently reported very low levels of female LFPR. It is important to bear in mind that while Haryana and Punjab are among the richest states within India, Bihar is the poorest state.”

Similarly, it pointed out that the northeastern and southern states have consistently reported relatively higher female LFPRs.

“Historically, the development and gender literature has offered cropping patterns as an important factor determining female LFPR,” it added. “Rice cultivation is typically correlated highly with female LFPR across countries.”

The authors did acknowledge that there were likely several other reasons as well for such “significant and persistent” differences across states.

(Edited by Radifah Kabir)

Also Read: Real wages grew just 0.01% over the last 5 years and contracted in Haryana & UP, Ind-Ra report finds