Mumbai: International investors are calling on India to throw open the doors to its sovereign bond market with the promise of more capital to finance its growth aspirations.

While the country’s famously protective policy makers have rejected previous proposals, there are hopes they are becoming more receptive to having India’s bonds included in global benchmarks as Prime Minister Narendra Modi sets his sights on doubling the size of the economy.

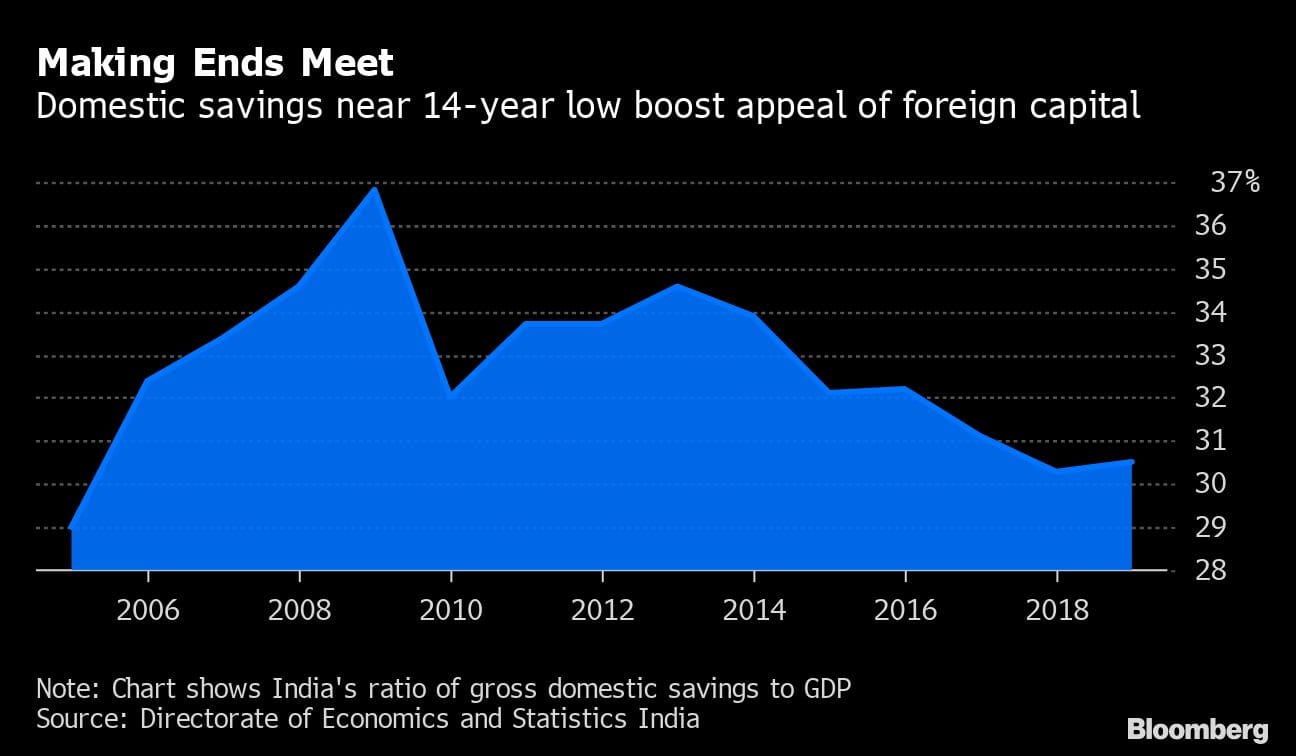

With waning domestic savings adding to the pressure for change, the government has already eased investment rules in sectors including retail, mining and manufacturing. China’s phased entry into several key bond gauges this year provides India with a template that could be shaped to its needs.

“We have ample room to open up to foreign portfolio investment debt flows,” said Ananth Narayan, a professor of finance and former South Asia head of financial markets at Standard Chartered Plc. “This would reduce financial repression of Indian banks, ensure a market price and accountability for government debt and free up our domestic savings for productive investments.”

Overseas investors hold just 3.7% of the almost 60 trillion rupees ($835 billion) of sovereign bonds issued by India, and the government has set a 6% limit on foreign ownership.

Overseas investors hold just 3.7% of the almost 60 trillion rupees ($835 billion) of sovereign bonds issued by India, and the government has set a 6% limit on foreign ownership.

This is a stark contrast to emerging-market peers like Indonesia, where there are no caps and global funds own about 40% of local currency government debt.

When Modi was in New York in September, the idea of more aggressively tapping the global debt market was floated. Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg News and Bloomberg Barclays Indices, announced that it would help Indian authorities navigate a course to inclusion in international bond benchmarks.

Road Ahead

The biggest hurdles are likely to be removing or significantly rolling back India’s limits on foreign ownership of sovereign bonds, and allowing the rupee to trade more freely on international markets.

Talks over inclusion in JPMorgan Chase & Co. indexes fizzled out in 2013 when officials balked at removing the cap. JPMorgan didn’t respond to requests for comment.

India will be cautious about any move to loosen its grip on the currency, which could have flow-on impact for export competitiveness and import costs.

Yet India may not have to drop its defenses in one fell swoop.

It could follow the path of China, which in April won phased inclusion into one of Bloomberg Barclays indexes. It also made it into a JPMorgan benchmark for 2020, even as concerns about liquidity, hedging and flexibility in currency execution and the settlement of transactions kept it out of FTSE Russell indexes. China removed its foreign investment limits on bonds and stocks in September.

“China provides a good road map for this process both in terms of steps and in terms of timeline,” said Bryan Carter, London-based head of emerging-market debt at BNP Paribas Asset Management. “If Indian authorities are serious about changes, we are still talking about a three-to-five year journey.”

The appeal of the nation’s debt to international investors is obvious, with India’s 10-year bonds offering yields around 6.5% in a world where trillions of dollars worth of debt now carry negative yields.

Also read: Global growth is slowing, World Bank chief says in fresh warning

‘Sticky Money’

For India, inclusion in global bond benchmarks could bring “upwards of $50 billion to $125 billion of new investment” in the economy, according to Bloomberg Economics’ Abhishek Gupta.

Advocates of India joining the indexes also argue that the country would also benefit greatly by attracting “sticky money” rather than “hot money” that races out when it is needed most in times of crisis.

Large institutional funds tend to be “benchmark huggers” who are effectively obliged to give member countries a permanent place in their portfolios, said Jan Dehn, the London-based head of research at Ashmore Group Plc.

Critics of India opening up can point to Indonesia.

While the Southeast Asian nation is a member of global bond indexes, and foreign inflows have made a huge contribution to its economic growth, Indonesia’s bonds and currency were taken on a roller-coaster ride in 2018.

Authorities in Jakarta had to buy back some of their own bonds and offload dollars, draining $10 billion from what had been a record stockpile of foreign-currency reserves. The central bank hiked its benchmark interest rate by 175 basis points, putting pressure on local borrowers.

Just like Indonesia, India’s government runs a budget deficit and the country as a whole has a current account deficit, meaning it needs funds from abroad to cover the gap between what it earns in exports and spends on imports.

Independent Streak

Wariness of foreign capital runs especially deep in India, reflecting a powerful desire for self-sufficiency that has guided much of the nation’s economic policy since independence from Britain in 1947.

As recently as July, plans to sell $10 billion in foreign-currency debt disintegrated amid a storm of criticism that India would be exposed to financial risks that it couldn’t control.

While there is a risk that India backs away from pursuing index inclusion again, the case for opening up the bond market is clearly gaining momentum, according to Narayan, the banker-turned academic who teaches at a management institute in Mumbai.

“It would mean a need for strict macro-economic discipline — overseas investors can punish us on wayward twin deficits, for instance,” he said. “Of course, such discipline and accountability might actually serve us well in the medium run.”

Also read: The 2020 economy should feel a lot better