New Delhi: India’s employment scenario has improved, but this improvement would be reversed if overlooked segments, such as unpaid family labour (UFL), are included in government employment data, according to economist Santosh Mehrotra.

According to Mehrotra, a developmental economist and visiting professor at the University of Bath, if the trend in UFL is taken into account, India’s employment scenario would show a downward trend, and marks “the worst form of reversal” in employment trends in India.

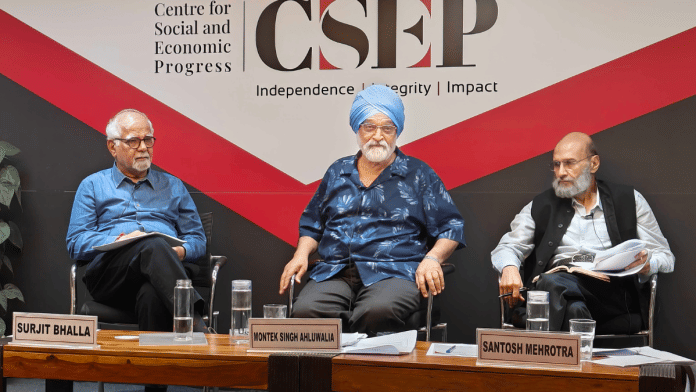

At a seminar, ‘Employment Generation in India – Facts and Figures’, organised by the public policy think tank Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP) Tuesday, Mehrotra said that the employment data and narrative promoted by the government and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) are flawed and need assessment.

He scrutinised the RBI’s KLEMS data and challenged the growth figures mentioned in the 2022-23 report.

“KLEMS report 2022-23 claims that employment grew by 80 million (8 crore) in the last 3-4 years, including 3 years of Covid, but there are question marks around it,” Mehrotra said. “How did employment grow in India when the ILO (International Labour Organisation) says that employment was stagnant in East Asia, and South Asia over the last few years?”

The KLEMS (K: Capital, L: Labour, E: Energy, M: Materials and S: Services) database provides employment estimates at all India-level, including public and private sectors.

He also asked where these 8 crore jobs came from if the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS)—the source of the KLEMS report—shows employment only increased from 54 crore to 57 crore in the past three years.

Mehrotra further said that the KLEMS data ignores the structural changes in India’s employment. He pointed out that women, especially in rural areas, showed higher engagement in agricultural and self-employment jobs.

He challenged the government’s perspective that the increase in women’s labour force participation, even in these sectors, is a positive growth. “It is the worst form of reversal of employment trend and a reversal of women leaving agricultural jobs since 2004.”

The economist also said that the number of people engaged in unpaid family labour increased from 55 million in 2018-19 to 95 million by 2022-23. Unpaid family labour is when an individual works in a farm/factory owned by a relative without pay.

Comparing the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) period of governance, Mehrotra pointed out that farm jobs fell for the first time in India’s history under the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) tenure.

He also critiqued the Modi government’s policy decisions such as demonetisation, and strict labour market regulations, which prompted a decrease in labour establishments, and a slowdown in the growth of non-farm jobs.

Mehrotra’s assessment, however, was challenged by Surjit Bhalla, former member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (PM-EAC) and former executive director for India at the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Bhalla argued that though the UFL was increasing in absolute numbers, it was falling as a share in the total workforce. He presented data from the PLFS that showed UFL decreased from 19.9 percent of the total workforce in 1999 to 15.5 percent in 2022.

He also countered Mehrotra’s claim that India needed more non-farm jobs, saying that India needs more employment, irrespective of sector.

Bhalla contended that the lack of employment in India is also due to the lack of labour. In this context, he pointed out that the recent fertility and immigration decisions over the years have stagnated the population of the country, affecting the supply of labour.

Both the panellists, however, agreed on one factor—real rural wages for workers have been stagnant over the last few years.

Mehrotra said that real rural wages— wages adjusted for inflation—for salaried employees have been stagnant since 2018. Bhalla agreed with Mehrotra on this, though pointing out that this trend was not exclusive to India. He, further expressed relief that the real wages were “at least not declining”.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: OBC representation in public sector companies improving, but still below Mandal Commission benchmark