New Delhi– “India, China and ASEAN should together work out a Panchsheel 2.0 and command it to the world,” former Singapore foreign minister, George Yong-Boon Yeo, said in Delhi Wednesday.

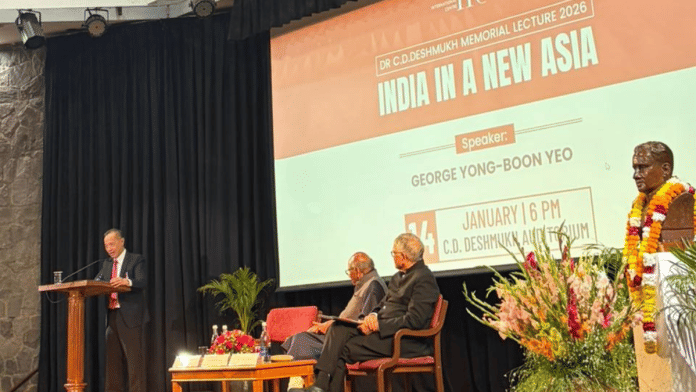

He was speaking at the 43rd C.D. Deshmukh Memorial Lecture at India International Centre. where, In the presence of India’s EAM, S. Jaishankar and former finance minister, P. Chidambardam, Yeo—who is the first Singaporean to receive the Padma Bhushan, India’s third highest civilian award– floated an idea: Asia’s two largest powers, together with Southeast Asia, should revive and modernise the principles that once anchored postcolonial diplomacy in the 50’s.

Call it Panchsheel 2.0, he suggested, with a renewed commitment to mutual respect, non-aggression, non-interference and peaceful coexistence, updated for an age of artificial intelligence, climate stress and multipolar rivalry.

“These are the principles humanity needs for the 21st century in a multipolar world,” Yeo said, referring to the original Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence agreed upon by India and China in the 1950s.

“We are ancient people. We know that you can’t change me, and I can’t change you—but you are worthy of respect,” he added.

The proposal comes at a moment when India finds itself, as Yeo put it, “on the move,” but moving through a far less forgiving global landscape than the one China encountered after joining the World Trade Organization in 2001. China, he said, enjoyed nearly two decades of uninterrupted growth, expanding its economy sevenfold in real terms before Covid-19. India’s rise began later and under heavier geopolitical pressure.

He said that trade wars, technological disruption and resurgent protectionism have narrowed the room for error. Yeo pointed to threats of draconian tariffs from Donald Trump as an example of the kind of pressure India now faces from the West.

Navigating this moment, he suggested, will require firmness without rigidity.

“You can’t show weakness, because if you show weakness, then it’s the end of you,” he said. “But you have to be flexible and practical.”

India and the RCEP

That balance in world order is already being tested by India’s energy ties with Russia, its historical defence relationship with Moscow, and Washington’s shifting priorities from Ukraine to the Indo-Pacific. If American interest in Ukraine wanes, Yeo argued, India’s oil purchases from Russia may matter less to Washington. But for now, New Delhi must establish a reputation for strategic autonomy, even at some cost.

At the same time, India must widen its economic horizons beyond the West as Southeast Asia, China and Africa then will be indispensable, Yeo said.

He also acknowledged India’s last-minute withdrawal from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), citing domestic concerns about farmers and fears of being swamped by Chinese manufacturing. But he was unequivocal about the long-term direction.

“I think eventually, India will join RCEP,” he said.

The key, he argued, is to ensure that the agreement continues to evolve in a way that allows India to join “in its own time,” on terms that reflect its domestic needs.

“The economies of India, China and Southeast Asia combined, are more than half the world. And the fastest growing half of the world. Which means that if we maintain the peace and have economic development for another generation, this region will pull the whole world around”, he added.

India in a New Asia

By the time Donald Trump returned to the White House, Yeo said, he had already learned to treat American politics as a form of stress testing. His former boss in Hong Kong, the billionaire Robert Kuok—now 102—once joked that the secret to longevity was waking up every morning to read what Trump had said overnight.

“Trump shoots up our cortisol level,” Mr. Yeo said dryly.

The real shift, he argued, has been underway for years: the consolidation of a multipolar world, one that the United States, for the first time, appears willing to openly acknowledge.

The past weeks have offered a preview. Venezuela, then Greenland, Cuba, Iran with crises coming by in rapid succession.

“He wants Canada to be the 51st state. He wants Greenland. He wants to take back the Panama Canal,” Mr. Yeo said. “This is about consolidating the hemisphere.”

Amid this, China’s technological strategy is diverging sharply from America’s. While Silicon Valley guards proprietary models, China has embraced open-source artificial intelligence.

“When China made DeepSeek open source, and then Alibaba followed, everyone entered the game,” Mr. Yeo said. “Including India.”

This, he believes, is transformative—economically, militarily, socially.

In Southeast Asia, countries have learned how to manage China: benefit from its growth without falling into its grasp. Doing so requires agility and balance.

“In this movement, naturally we look to India as a counterbalance,” Yeo said.

The problem is that ASEAN–India ties remain far below potential. Mr. Yeo recalled the early 1990s, when India’s economic reforms caught Singapore’s attention, and the skepticism that preceded the landmark India–Singapore trade agreement.

Yet India’s growth, he argued, ‘is organic and irreversible’ and nowhere are the stakes higher than in India’s relationship with China, Yeo said as he described the 2020 Galwan Valley clash as a turning point that hardened suspicions on both sides.

The asymmetry of historical memory compounds the problem. “The 1962 war is still remembered in India as if it happened recently,” Yeo said. “It’s largely forgotten in China.”

And yet, he noted, both countries are being pragmatic. China has begun issuing visas to Indian travellers. Reports indicate that India may allow Chinese firms to bid for public tenders.

He then recalled a moment from 2010, traveling near the Nathu La Pass in Tibet, when a Chinese official remarked that he hoped one day to drive to Kolkata. Strategists may disagree at the idea, Yeo acknowledged, but trade corridors could transform entire regions if peace holds.

“Hundreds of millions of Chinese will benefit,” he said, “and Calcutta will boom.”

For Southeast Asia, Yeo said, conflict between India and China is like a quarrel between parents. “We feel great pain,” he said. Singapore, where the strategic mandalas of India and China intersect, has every incentive to facilitate rapprochement.

That is what makes the idea of Panchsheel 2.0 more than nostalgia. The original principles underpinned the Bandung Conference and later the Non-Aligned Movement. Reimagined today, they could offer a moral framework for a fracturing world.

“It will take time,” Yeo added. “But people will begin to sign on.”

(Edited by Niyati Kothiyal)

Also read: Chinese commentary on Iran protests — serious but not regime-threatening