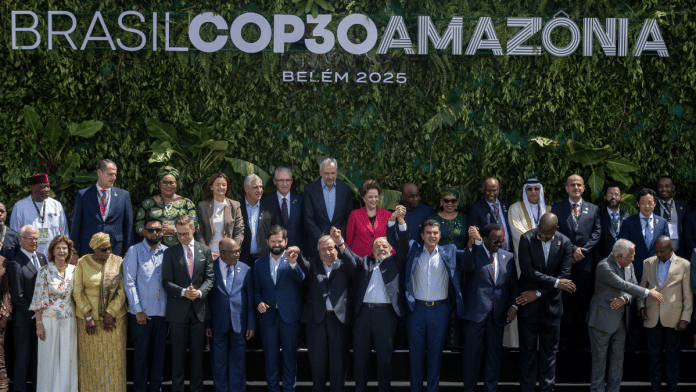

World leaders have departed the sprawling COP30 venue in the Amazonian city of Belém, Brazil, after hammering home the message that efforts to tackle climate change are moving too slowly.

Now the real work starts.

Over the next two weeks, negotiators from nearly 200 countries will thrash out the technical details on everything from how best to cut emissions to the structure of funds to help the poorest deal with the impacts of increasingly extreme weather.

Any final deal will mean somehow finding a consensus that can be tolerated by both the world’s biggest fossil fuel producers and the small island states on the frontlines of sea level rise, at a time when other issues, like trade and war, are displacing climate from the top of the international agenda.

“This is really going to be a very different COP” from United Nations Conference of the Parties summits held in recent years, COP30 President André Corrêa do Lago said last week. “It touches so many sectors of the economy that countries really have to be very careful, because no country in the world is ready for the transition.”

Here’s what to watch:

Agenda fight

Some of the biggest fights of COP take place on Day One, as countries hash out which items should get formal spots on the conference agenda. This year is no different.

Negotiating groups already have advanced several topics for consideration and have until Monday morning to propose more. But setting the agenda requires consensus among delegates, and several of the proposals have provoked friction among countries.

For instance, the group of Like Minded Developing Countries, which includes Saudi Arabia and India, wants to discuss a Paris Agreement provision that calls on developed countries to offer climate finance to poorer nations. It also wants to put on the agenda so-called unilateral trade measures — a thinly veiled reference to the EU’s levy on emissions-intensive imports, which goes into effect next year.

Conversely, the Alliance of Small Island States wants an item on how to respond to a recent report by the UN that showed the world is still well off course keeping global warming below the 1.5C goal outlined by the Paris Agreement. The alliance could face opposition from countries like Saudi Arabia that have resisted any more language on boosting ambition.

Brazil has suggested folding those agenda items into an existing negotiating track along with finance, setting the stage for a broader final decision, according to people familiar with the matter.

The whole effort is overlaid by some countries’ clamor for a cover decision or other broad response to the UN’s sobering assessment of the world’s emission-cutting progress so far. Brazil is meeting heads of delegation on Sunday afternoon in hopes of striking a grand bargain and avoiding a standoff.

Fossil fuel road map

After last year’s $1.3 trillion deal on climate finance, developed nations are trying to shift the conversation back to mitigation in order to keep 1.5C alive. At COP28 in Dubai, countries committed to transitioning away from fossil fuels, yet none of the more than 60 updated national climate pledges since then have put in place targets to reduce oil and gas production.

During his COP30 opening address, Brazil’s President Lula Inácio Lula da Silva said the world needed a road map to “overcome” its dependence on fossil fuels. Agreeing a way forward on that in Belém would be seen as a major victory by progressive countries and activists. However, it’s not clear where a new, transition-oriented initiative might fit in the COP process.

Countries at COP28 already agreed they’d contribute to “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner,” without setting criteria for what that looks like in practice.

“The truth is that all the fossil-producing countries have agreed to transition away, so we have a mandate,” do Lago told reporters Sunday. “Let’s talk about it.”

“It is clear that the fossil fuel industry is not preparing for just, orderly and equitable transition,” said Kalani Kaneko, foreign minister for the Marshall Islands. “Instead, we see a future of supply shocks, conflict of resources, stranded assets and the legacy of dangerous climate change being visited upon us to serve the interest of others.”

All eyes on Trump

The US is pulling out of the Paris Agreement, with its exit teed up for Jan. 27 next year, and it hasn’t registered any delegates to attend the talks. Yet US officials could show up at any time until the final gavel falls, since the country still remains part of the Paris accord and the underlying framework convention on climate change.

Even if that doesn’t happen, the US looms over the negotiations. Under President Donald Trump, the country has asserted a full-throated support for fossil fuels — and a disdain for confronting climate change — and has worked to disrupt action in other multilateral fora, including negotiations on plastics and shipping emissions.

Adaptation

Unlike its past two editions, COP30 doesn’t have a big headline deliverable. But one area where negotiators could make real progress is by elevating the need to adapt to climate change — an issue that was highlighted when Hurricane Melissa ripped through Jamaica, causing as much as $4.2 billion of damage.

Talks will focus on the need to narrow down a list of climate resilience indicators from 400 to about 100 by the end of COP30, resulting in a clearer set of criteria for policy assesment and support. An existing goal to double adaptation finance expires at the end of this year, and some delegates hope a new target will replace it.

“This COP needs to agree on an adaptation package with a new finance goal at its heart,” Kaneko said. “Our adaptation needs are overwhelming.”

(Reporting by John Ainger and Jennifer A. Dlouhy. With assistance from Akshat Rathi and Alfred Cang.)

This report is auto-generated from Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.

Also read: Modi unlikely to attend COP-30, Environment minister Yadav to lead Indian delegation to Brazil