With little fanfare, the Trump administration demolished the East Wing of the White House in order to make space for a new 90,000-square-foot ballroom. President Donald Trump teased the project for months, first announcing his plan to build a $100 million addition back in February. But the Trump administration didn’t originally say that construction of the ballroom — whose price tag has since more than tripled — would require the entire East Wing to be razed.

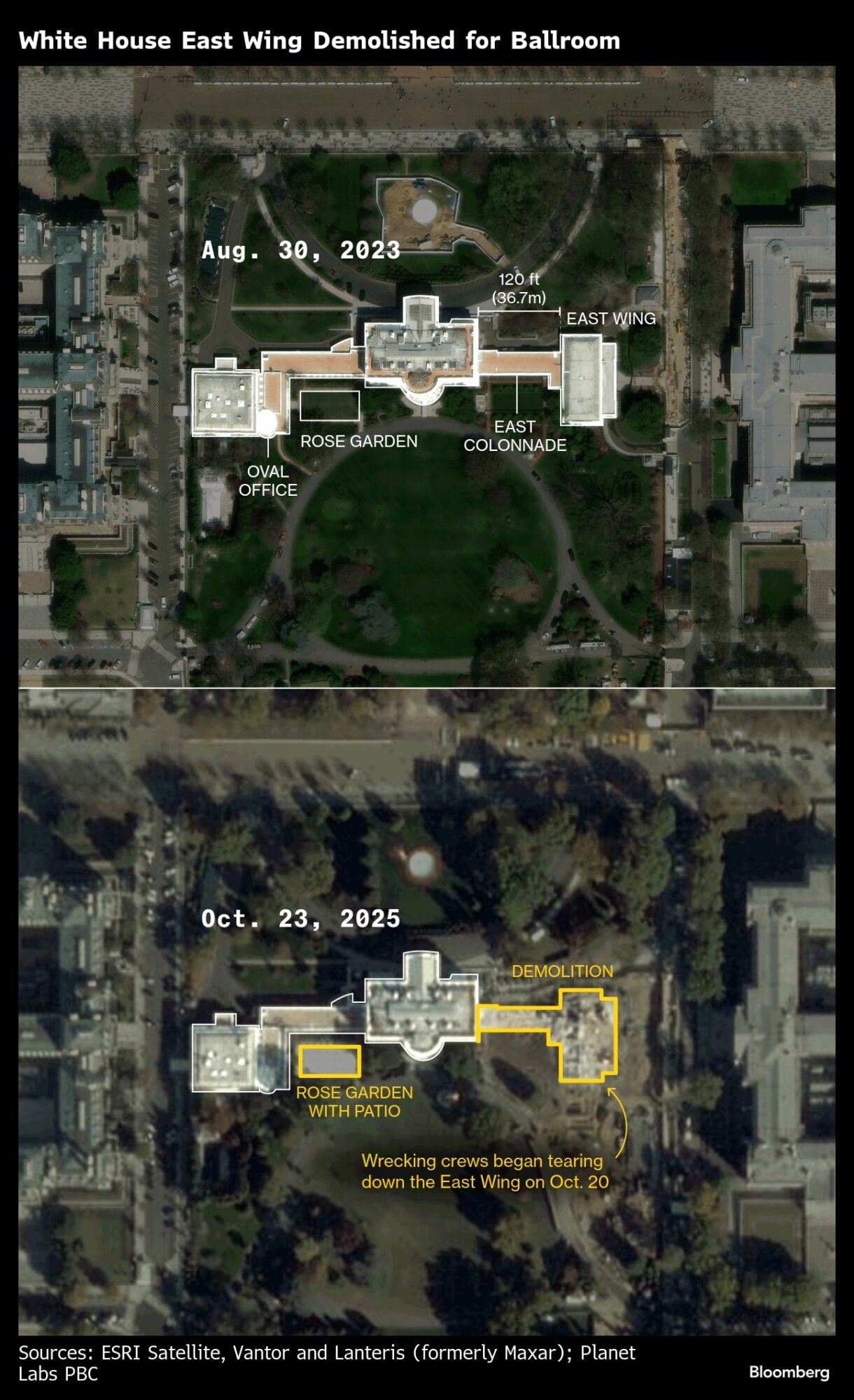

The demolition trucks that began pulling down the East Wing on Oct. 20 surprised both the general public and historians and architects who didn’t realize that the most prominent civic building in the US could be altered so dramatically without public discussion. Traditionally, changes to historic public structures undergo careful review by government agencies.

What is Trump doing to the White House?

Excavators tore down the East Wing after Trump ordered its demolition to build a ballroom in the same spot. The demolition marked the biggest construction effort to the 225-year-old building since the 1940s.

Trump unveiled his ballroom plans over the summer, after long complaining about wanting a larger room for entertaining at the White House. At the time, the president said the work on the White House grounds wouldn’t “interfere with the current building” and that the project’s plans paid “total respect” to the existing structure’s architectural style. He also pegged the total cost at around $200 million.

On Oct. 22, as the demolition proceeded, Trump said the price tag had risen to $300 million but would be paid entirely by “me and some friends,” including donors. On Oct. 23, he upped the figure to $350 million.

White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt defended the project. “There have been many presidents in the past who have made their mark on this beautiful White House complex,” she said on Oct. 23. “The East Wing is going to be more beautiful and modern than ever before. And in addition, there will be a big, beautiful ballroom that can hold big parties and state visits for generations to come.”

Trump’s planned addition would be substantially larger than the main White House building, which is about 55,000 square feet.

Is the president allowed to make such significant changes to the White House?

The White House is exempt from some rules that would apply to most other projects.

Federal historic preservation laws require historically significant properties to undergo extensive review prior to renovation. Properties that are 50 years or older fall under the scope of the National Historic Preservation Act, a 1966 law that launched the industry known as cultural resource management. Section 106 of the law requires the federal government to carefully document the cultural impact of any sale or alteration of a historic federal building. Such Section 106 reviews are familiar to builders and developers in Washington.

However, the law doesn’t apply to the White House, the Supreme Court or the US Capitol, as they are considered living properties, exempt under the 1966 act. The Washington, DC, department of buildings, which would typically handle permits, also said it has no jurisdiction over the White House.

What was the East Wing used for?

The East Wing, itself an addition to the White House, was constructed in 1902 and expanded in 1945. It housed the offices of the first lady as well as the president’s social secretary. The East Wing sat on top of a secure underground bunker known as the Presidential Emergency Operations Center that was built during World War II and will be upgraded during construction.

Older elements of the mansion not considered part of the East Wing also were demolished for the ballroom project, including the East Colonnade added by President Thomas Jefferson in 1805.

What other changes has Trump made to the White House?

Trump has been putting his stamp on White House decor and architecture since he began his second term in January. He had the White House Rose Garden paved for a patio and replaced chandeliers and artwork in the complex.

Are there any precedents for what the Trump administration has done?

While the White House isn’t subject to federal historic preservation laws, past administrations have traditionally sought reviews for additions to the White House. But changes as sweeping as the demolition of the East Wing have no real precedent.

While not subject to historic-preservation review, the demolition disregards the many procedures set forth by Congress, oversight agencies and past White House occupants to safeguard the building’s history, preservation experts said.

Projects to alter historic federal properties or build within Washington’s core fall under the purview of at least two federal agencies, the National Capital Planning Commission and the Commission of Fine Arts. Other recent alterations to the White House property, including the addition of a tennis pavilion during Trump’s first term, followed the review process. Trump’s more recent decision to pave the Rose Garden did not.

Neither NCPC nor the CFA has the power to stop a federal project, and indeed, President Harry S. Truman added a balcony to the White House without CFA approval. So far, the Trump administration hasn’t submitted its plans for a ballroom for review, but it said on Oct. 21 that it plans to do so.

The teardown also violates norms of historic preservation, especially for changes to the nation’s most visible and important structures, according to preservationists.

President Richard Nixon outlined the federal government’s responsibilities in a 1971 executive order — which is still in place today. “The Federal Government shall provide leadership in preserving, restoring and maintaining the historic and cultural environment of the Nation.”

Preservation laws also provide transparency for workplace safety and building regulations — rules set forth by the Environmental Protection Agency and Occupational Safety and Health Administration to monitor for the presence of asbestos, for example. Given the era when the East Wing was built, asbestos may be present in the building’s concrete, roofing and insulation.

The demolition and construction companies involved in the ballroom project, Silver Spring, Maryland’s Aceco Demolition and Bethesda, Maryland–based Clark Construction Group, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

(Reporting by Kriston Capps with assistance from Adrienne Tong and Krishna Karra)

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.