Delhi: Deepti Bansal considers herself no less than an activist, intent on telling the world the ‘ways of Baniyas’. Through her snack brand Being Bania, she is giving the cuisine its long overdue recognition and reviving lost flavours. Sundried sangri, a Marwari delicacy, is their bestseller. “Yes, we have it,” she said, as a loud cheer from a customer erupted on the other end of the line.

The Baniyas have conquered trade, finance, technology. And now, they have plunged into the food world – and they want to be at the top there too.

“I am Baniya, and I know my culture deeply. That’s when it occurred to me — why not talk about my own food? Because nobody else is talking about it,” said Bansal, a poised woman with a soft voice.

Bansal and her cofounder Konark Murarka are the new generation of Baniya entrepreneurs who are blending tradition with the new age digital market of packaged food on Blinkit and Amazon. Their brand dives into traditional community food habits: from pickles to papad to gatte ki sabzi, all packaged under a logo of the old-style munshiji, with cap, moustache and teeka. Every item is prepared in line with Baniya rules — no garlic, no onion.

Onion and garlic are ugra (violent) food items—they create agitation inside you. And if we’re agitated, how will we run a business? Have you ever seen a Baniya lose his cool?

-Chef Gunjan Goela

Baniya food isn’t new, but it has usually been lumped under generic vegetarian snacks. Now a more assertive identity is coming to the fore. The landscape of Baniya and allied regional cuisines, from Malwa to Marwadi, is now more visible through marketing and branding.

On Amazon, there’s clove-infused sev packaged as “Bania Bhaiyaji Ratlami Sev”. Indore’s Malwa Story sells sevs of every shape, from Ratlam to Ujjaini. Its IIT-IIM educated founder Akshansh Gupta calls it “an attempt to make the world fall in love with sev.” Rajasthan has Marwari Bites, with 25 kinds of khakhra and “thin bites”. Its logo, and even cursor, is a turbaned, moustachioed figure. Another label, Baneeya Sa, sells mathri, boondi and Mewari chana dal on Amazon, also with a turbaned mascot. In Gurugram, Baniya’s Kitchen serves thalis for Holi, Navratri, and corporate parties. There is even a rigorously researched cookbook, The Baniya Legacy of Old Delhi: Culture and Cuisine, by chef Gunjan Goela.

The demand for Baniya food has been growing since the 1990s, according to Goela, who was the first to introduce Baniya cuisine to the vegetarian menu at ITC.

“It took vegetarians by storm. They didn’t know food could taste this good without onion and garlic,” said the 60-year-old consultant with ITC, herself a Baniya. She has since catered for Ambani, Adani, Amitabh Bachchan, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“They all love my food,” Goela said, seated in the living room of her plush home in Delhi’s Civil Lines.

The community is strict about its eating practices, she added. For Baniyas, the kind of food they eat is a vehicle to the success in their businesses.

Being Bania has taken this community food movement a notch higher. And their customer base includes not just Baniyas, but people from across the country who are interested in exploring the community’s food culture.

“Whenever you think of what Baniyas eat, you simply reduce it to potato. Yes, they eat a lot of them. But they don’t only eat potatoes,” Bansal said.

For her and Murarka, building the brand has also meant a personal reconnect with the community and its old roots and routes.

“I didn’t know several food items that we used to eat. Because of migration and modernisation, our traditional eating habits have taken a backseat,” she said. “When I asked my parents, ‘Do you eat this?’ they said, ‘We used to eat it, but now nobody does – so, we don’t either’.”

Also Read: The Aggarwal crisis in India. They have everything but no one good to marry

Commerce and love, Baniya-style

At the three-floor Being Bania office in Delhi’s Badli, Deepti Bansal sits in a modest room with plain white walls, a rolling chair, and a simple wooden table. From here, she oversees the operations of the factory-cum-warehouse. A staff of 20 now handle the work she did alone until a couple of years ago— cleaning, packing, dispatching food.

In the cooking area, a woman wrestles with a large kadchi and a hot, oily pan as she fries papads — the kind Baniyas like loaded with spices. “I’ve made a box of papad!” she shouts. A young man rushes in to carry it to another room, where the papads cool before being carefully packaged.

“Baniyas can’t eat their food without papad and pickles,” Bansal said with a smile.

In India, the food choice changes every 100 kilometres. That is what prompted us to come up with a brand that caters to Baniya food habits

Deepti Bansal, co-founder of Being Bania

When the brand was taking its baby steps in 2021, Bansal was the worker, the creator, the designer, and the founder, all at once. With business taking off, others have been hired to take on some of those roles, but she’s now the poster girl for the brand. On the Being Bania website, her photo appears alongside the brand’s signature pastel-and-black packaging. In another image, she’s seen relishing traditional Baniya namkeen. A pop-up on the site invites customers to “taste the culture.”

While papads and pickles are made at the Badli factory, other traditional specialities like gatte and sangri are sourced from vendors in Rajasthan.

“We first thought we should get the vendors here, but they were not willing to shift their base to Delhi. So, every month we procure food items from them,” said Bansal.

The brand has grown over 100 per cent year-on-year, scaling from Rs 50,000 a month to over Rs 50 lakh in monthly revenue, according to Bansal. They deliver over 30,000 units monthly and are now on track to hit a $1 million annual run rate, she added.

It all began five years ago as a dinner table conversation between two friends, Konark Murarka and Ishan Pardesi. Both were sales managers, travelling constantly and craving home-style food.

“In India, the food choice changes every 100 kilometres,” said Bansal. “That is what prompted us to come up with a brand that caters to Baniya food habits.”

Murarka, a Baniya, and Pardesi, a Punjabi, initially floated a company called Big Brands Consumer Private Limited, planning to market both Punjabi and Baniya food. It was around this time that Bansal entered the picture. She was hired as a designer but as they thrashed out the details of the business, she became a co-founder as well.

“Punjabi food is well-known, not Baniya food. That’s when we made a list of Baniya food and what they eat,” said Bansal.

They began researching community food habits, reaching out to families and relatives, studying market supply and demand, and visiting Rajasthan — the hotspot of Baniya cuisine. In Khatu Shyam and Bikaner, they explored markets for ker, sangri and beans, bringing back samples for Delhi chefs to identify the most authentic flavours.

But as Bansal and Murarka worked side by side for months, something else was cooking — a love story. Just before the brand’s official launch in 2021, Murarka told her, “You bring out the best in me.” She replied, “You do the same for me.”

Their food preferences aligned too. Both dislike sangri and both cherish kair ki sabzi. The brand became personal, a way to put old food traditions back on the table, and also to build something together.

In the Baniya world, food itself is as much about commerce as it is love.

Right tastes for business temperament

For Baniyas, their food complements their business mindset. They avoid onion and garlic to maintain a calm temperament, essential for business dealings, according to chef Goela.

“Onion and garlic are ugra (violent) food items—they create agitation inside you. And if we’re agitated, how will we run a business?” she said. “Have you ever seen a Baniya lose his cool?’

But the right kind of food was rarely available in hotels and restaurants where many Baniyas struck business deals. When Goela joined ITC in 1998, Baniyas and Jains rarely ate at the chain’s hotels. She proposed adding Baniya dishes made without onion and garlic. It served two purposes: vegetarians now had a wider choice, and Baniyas and Jains became dedicated ITC customers.

“After a few months, I designed a new vegetarian menu that included Baniya food. ITC became a banquet for them,” she added.

Baniyas are very stubborn about their eating practices, according to her. In earlier days, women had clothes set aside only for cooking, and no one else was allowed to touch them.

“Baniyas are very much into purity and impurity. Except a Brahmin or someone from their community, they don’t let anyone cook. They do a lot of background checks,” she said.

Goela has since turned her knowledge into a book. In 2023, she published Baniya Legacy of Old Delhi: Culture and Cuisine, providing an intimate glimpse into the eating habits of the community along with recipes.

We use a lot of hing, dahi, malai, and aamchoor for the gravy. Our method of cooking is different

-Neha Gupta, home chef at Baniya Kitchen

“A typical meal in the afternoon would comprise arhar ki dal, chawal, bhune alu and another sookhi sabzi like baigan or tinda. Alternatively, there would be kadhi-chawal. No meal would be complete without dhaniya-pudina chutney,” a passage reads. In August, she presented a copy to Delhi Chief Minister Rekha Gupta.

For Goela, documenting Baniya food culture was necessary because no one had done it before. It was ubiquitous yet unheralded. Her inspiration came from her mother, who was deeply strict about the Baniya diet. Even at five-star hotels like the Oberoi, she would only eat naan and curd with pepper and salt.

“There weren’t many options for her,” said Goela. “That’s when I thought I should do something to make Baniya food accessible — anywhere and everywhere.”

Since the purity-obsessed days of yore, the community has evolved. While they stuck to freshly cooked food from their own kitchens before, they are now a little more adventurous and not averse to eating out. That makes preservation all the more urgent to her.

“Wherever I go, for lectures on gastronomy or to speak to students, I insist on them learning about Baniya food,” said Goela. She wants it to go mainstream and with the Baniya stamp.

Meanwhile, some home chefs are serving the market for Baniya food from their own kitchens.

Neha Gupta, 42, has been running Baniya Kitchen in Gurugram for seven years. It brings a taste of Chandni Chowk to the city.

“It was my love for Old Delhi Baniya food that made me become a chef,” she said.

Even within the community, she points out, there are divides. Delhi Baniyas refer to others as bahar wale Baniya. During Navratri too, their food differs. Instead of tomatoes, they use curd and cream for tang.

“We use a lot of hing, dahi, malai, and aamchoor for the gravy. Our method of cooking is different,” said Gupta.

Also Read: Traditional Baniya banquets had no paneer. The most exotic dish was raswali matar

Papad and pickles for pan-India plates

Despite being a Baniya, Deepti Bansal had to dig deep to get to the roots of the community’s dishes. Apart from multiple trips to Rajasthan, she mined her family members’ memories.

One story her grandparents told was of a famine that had struck the region. With no vegetables at hand, gatte ki sabzi was born — thin rolls of gram flour mixed with masala, cut into pieces, and fried. It eventually became a staple of the community.

Bansal, who was born and raised in Lucknow, was hearing these stories for the first time.

“Rajasthan doesn’t have a lot of vegetation. After the famine, people started storing peas, pods, and drying them. Vegetable dishes made from gram flour and spices were born out of that necessity,” she said.

Those ancestral preparations are now procured directly from Khatu Shyam and Bikaner, stored in Being Bania’s Badli warehouse, and sold on Amazon, Flipkart, and most recently Blinkit, where it launched two months ago.

What surprised the founders was that many of their customers weren’t Baniyas. It showed them that the Indian market was curious about what Baniyas eat.

“They were from South India, Bengal, and Bihar. And we were utterly surprised,” said Bansal.

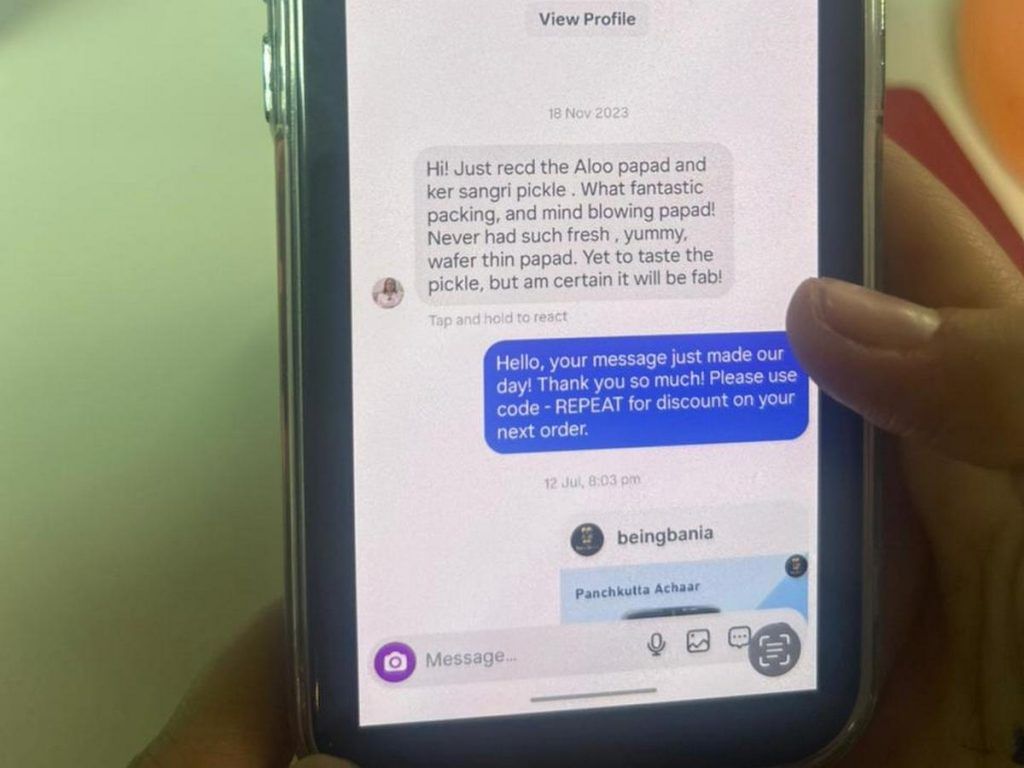

She proudly showed off numerous complimentary messages from customers. One praised the ker sangri achaar and aloo papad.

“We are regular customer at Swiggy Instamart and love your product too much. It gives us authentic traditional taste as prepared by our nani and daadi,” it said.

In the last three years, Being Baniya has achieved around 60 per cent repeated customers. The next step, Bansal said, is to strengthen their presence within Baniya groups and join the World Baniya Forum, a community platform of businesspersons, entrepreneurs, investors, and other professionals.

“It is for everyone to explore Baniya food. But for Baniyas to know first that their traditional food is just a click away,” she added with a laugh.

This is the third article in Baniya Basics, a three-part series on the changing face of India’s mercantile community.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)