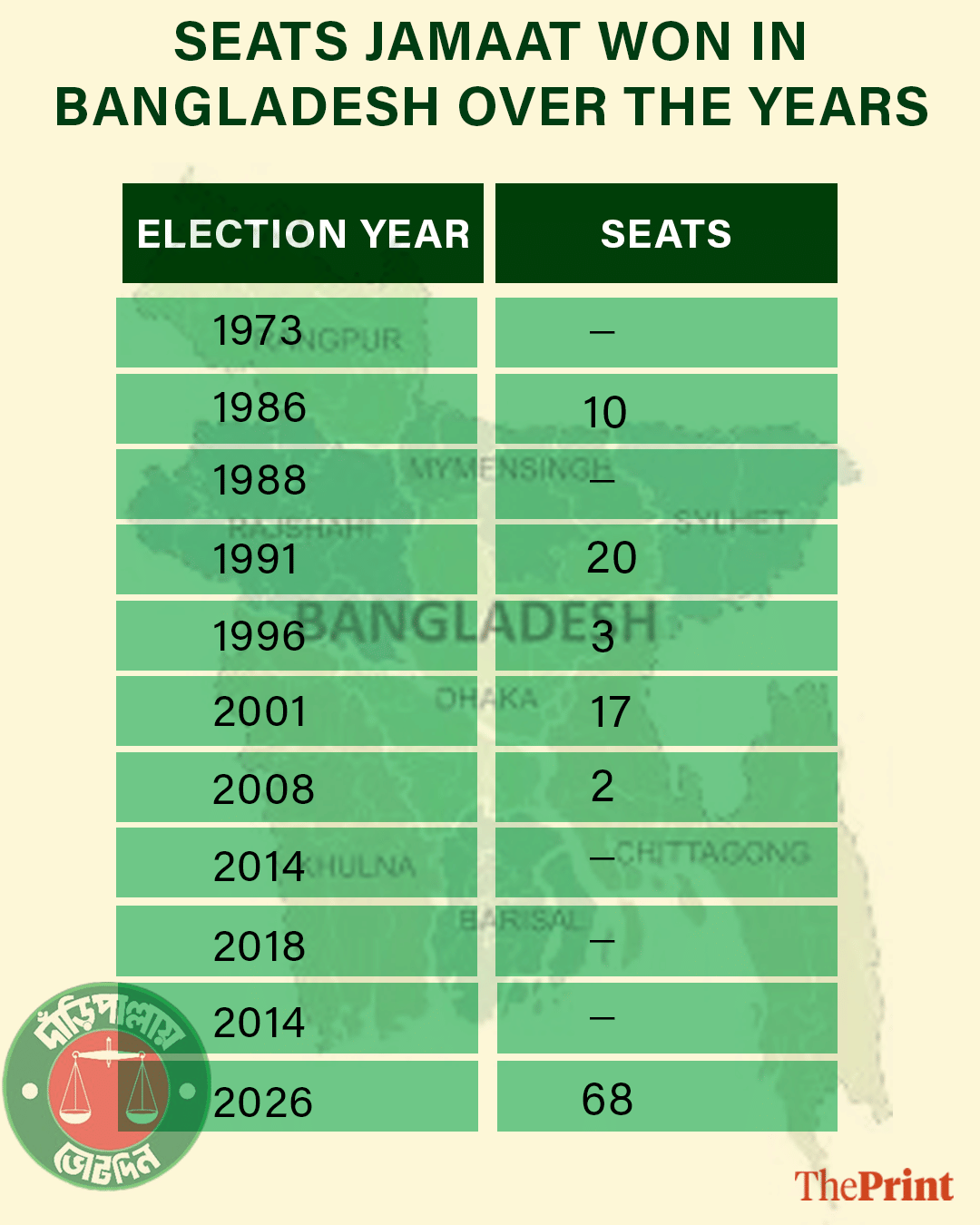

Dhaka: The just concluded general election marked a major shift in Bangladesh’s political landscape. Jamaat-e-Islami, banned until August 2024, not only pulled off its highest seat tally and vote share yet, but also surpassed Jamaat offshoots in the Indian Subcontinent.

Of the 299 seats in Bangladesh where polling was held on 12 January, Jamaat won 68, making it the only offshoot of the Jamaat-e-Islami in the Indian Subcontinent to have a sizable number of representatives in the legislature.

Founded in 1941 in Lahore by Islamic scholar Abul A’la Maududi, the movement envisioned a political order guided by divine sovereignty, and enforced through Islamic law. Maududi called it “theo-democracy”. As an organisation, Jamaat never functioned in a silo. For decades, its branches moved along the edges of power in South Asia—ideologically influential, with a disciplined cadre, but never dominant at the ballot box.

With the outcome in Bangladesh, that’s no longer the case.

Jamaat’s resurgence was aided by its dense network of affiliates, including Bangladesh Islami Chhatra Shibir. Success in student union elections at major universities helped build momentum among younger voters. Analysts ThePrint spoke to also pointed to increased support among rural women and constituencies with a large presence of youngsters.

International dynamics add another layer. The resurgence of Islamist politics in Bangladesh comes as such movements face pressure elsewhere in the Muslim world.

Analysts ascribed Jamaat’s electoral turnaround in Bangladesh to four factors: outreach, appeal in rural areas and among the youth; complacency of the two major parties; Awami League ban; and a ‘reformist’ agenda under Jamaat’s current emir, Dr Shafiqur Rahman.

“A significant portion of Bangladesh’s population continues to live below the poverty line, earning less than $2 a day. For these voters, the promise of democracy alone has not translated into better livelihoods. Jamaat’s consistent presence through charity, clinics, schools and relief work has helped it build trust where the state has often seemed absent,” Asif Shahan, author and professor at Dhaka University, told ThePrint.

The Bangladesh offshoot of Jamaat traces its roots to the East Pakistani wing of Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan. During the 1971 Liberation War, it opposed Bangladesh’s independence and staged pro-Pakistan demonstrations. After the formation of Bangladesh, the government of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman banned Jamaat. The prohibition was lifted under President Ziaur Rahman, paving the way for the formal establishment of the political party in 1979.

For much of its history, Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami functioned as a coalition-dependent force, most notably alongside the BNP. Two of its leaders served as ministers in the BNP-led coalition government between 2001 and 2006.

But under Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, its registration was canceled in 2013.

Senior leaders including Ghulam Azam and Delwar Hossain Sayeedi were prosecuted by the Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal for war crimes dating back to 1971; many including Motiur Rahman Nizami and Muhammed Kamaruzzaman were hanged. Jamaat was banned again by the Awami League on 1 August, 2024, amid student-led protests.

After Hasina’s ouster, the interim government led by Muhammad Yunus lifted the ban and the party’s registration was reinstated, paving the way for its return to Bangladesh politics.

Yet controversy persists. Three days before polling day, women’s rights groups organised nationwide protests over Shafiqur’s now-deleted social media post equating all working women with sex workers.

Also Read: Not pro-anyone, pro-economy—Bangladesh PM-elect Tarique Rahman sends clear global signal

Mapping Jamaat’s gains

Bangladesh Election Commission data shows Jamaat-e-Islami got 31.76 percent of the total votes polled, making it the second-largest party after the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which secured a vote share of 41.97 percent.

Crossing the 30-percent mark signals a major expansion of Jamaat’s electoral base, given that its previous peak performance was around 18 percent (1991). Barring the 10 seats it won in 1986, 20 in 1991 and 17 in 2001, its seat tally was restricted to single-digits.

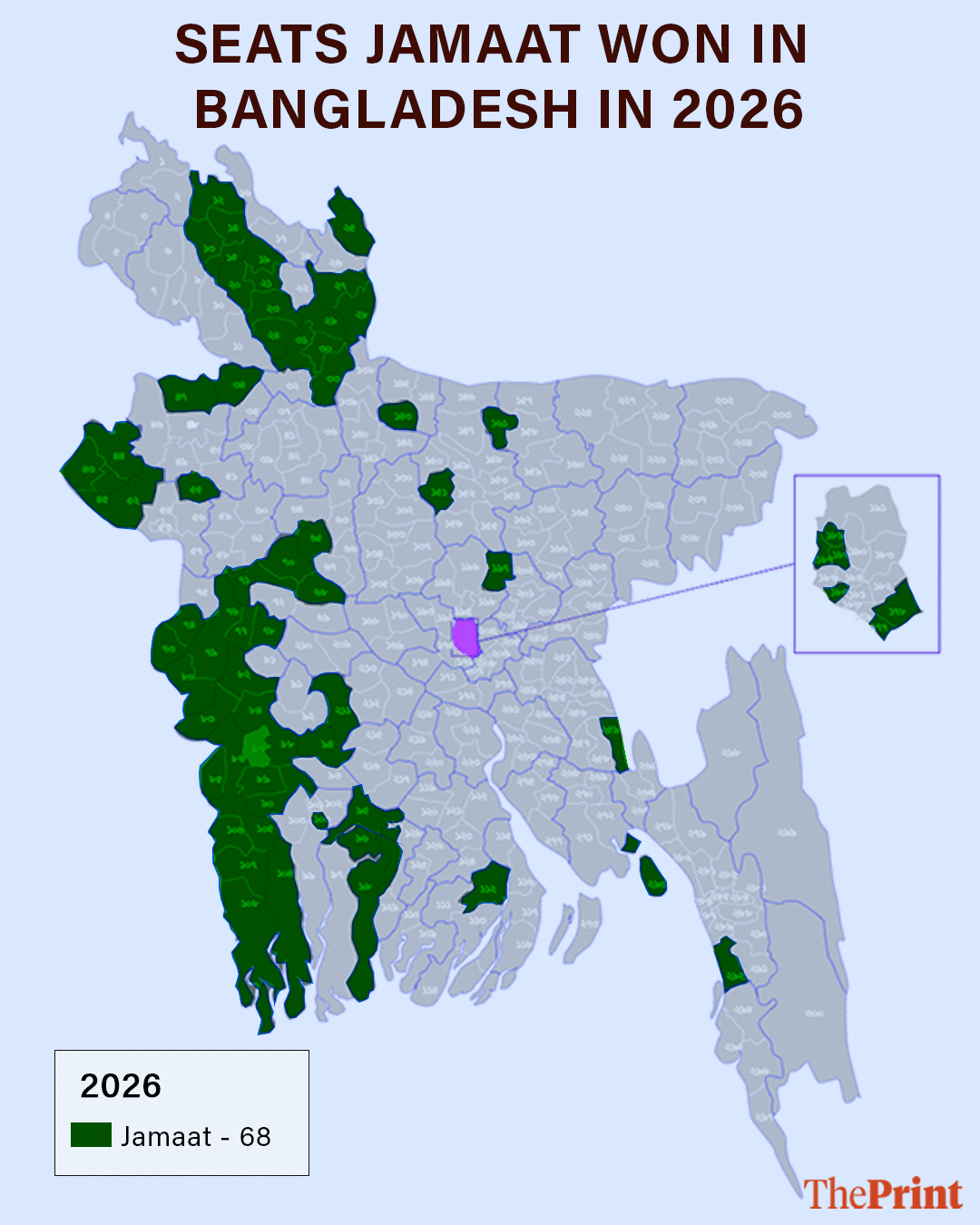

This time around, Jamaat recorded its biggest electoral gains in Khulna division (winning 25 of 36 seats), Rangpur (16 of 33) and Rajshahi (11 of 39). It swept all seats in Satkhira, Meherpur, Chuadanga, Nilphamari and Chapai Nawabganj districts. For the first time, it won 6 of 15 seats in metropolitan Dhaka and an ally won the seventh. In many other Dhaka seats, the margin of loss was narrow. For instance, it lost Dhaka-10 by 3,300 votes.

The party even fielded a Hindu candidate in Khulna, who eventually lost.

The data clearly shows that Jamaat is strongest in the Khulna division, securing 48.26 percent of the vote—even ahead of the BNP with 43.55 percent. This makes Khulna in south-western Bangladesh its electoral stronghold, besides Rangpur division in the north where its vote share was 39.78 percent, as opposed to the BNP’s 41.95 percent.

Jamaat also put up a fight in other parts of the country. In Rajshahi, for instance, it secured 39.71 percent of the total votes polled, showing strong consolidation despite trailing the BNP. Together, Khulna, Rangpur and Rajshahi form a corridor running along Bangladesh’s western borders where Jamaat’s rural and semi-urban support appears most entrenched.

Earlier, these areas were seen as strongholds of the Awami League.

In contrast, Jamaat’s performance was moderate in other divisions. It got 28.01 percent in Chattogram, compared to the BNP’s 51.88 percent. In Barishal, it got 23.46 percent, and in Sylhet, 22.62 percent, as opposed to the BNP’s 47.64 percent and 59.54 percent. In Mymensingh, Jamaat’s vote share was 21.85 percent, and the BNP’s 51.60 percent.

In Dhaka, the country’s political and economic center where Jamaat had historically never gained much ground, it secured 22.38 percent of the vote. The BNP, though, maintained a strong lead there with 51.41 percent along expected lines.

Overall, the redrawn electoral map shows Jamaat’s appeal is strongest in rural and semi-urban northern and southwestern regions, while it remains relatively weaker in wealthier, urban, and diaspora-influenced divisions such as Dhaka, Sylhet and Chattogram.

What is also clear is that Jamaat is no longer a fringe electoral force in Bangladesh, but a major national contender with concentrated regional strongholds and a significantly expanded vote base. ThePrint looks at what explains this shift.

What worked in Jamaat’s favour

Jamaat’s electoral breakthrough followed a strategic break from the BNP. It floated an alliance after 17 years and partnered with the National Citizen Party (NCP) comprising prominent faces from the anti-Hasina stir. But there is more.

“When asked what drives Jamaat’s rural support, three factors stand out: its visible charity and grassroots presence; the perception of ethical leadership compared to mainstream parties; and its blending of Muslim identity with promises of economic reform,” said Asif Shahan. He explained that Jamaat projected itself as an advocate for an Islamic welfare society and a supporter of tax cuts. It also promoted social work through charities.

Dhaka-based political analyst Mohammed Tanvir added, “When the same political cycle continues for many years, voters naturally begin to look for alternatives. A party that appears different or less tested can start to represent new hope, new language, and new promises about the future. That psychological shift alone can create space for a comeback.”

Tanvir said a sense of exclusion or unfair treatment can also generate sympathy over time.

In the case of Bangladesh, Jamaat’s supporters pointed to over fifteen years of ‘repression’ under the Awami League government. Many senior leaders were executed after controversial trials, thousands of leaders and activists were detained, and the party struggled to function with a clear political identity or constitutional space. For many of Jamaat’s sympathisers, this created a strong narrative of endurance and survival, which can gradually translate into empathy and eventually political support, said Tanveer.

He also pointed out that organisational continuity is very important. According to him, even when a party is not highly visible, it may still maintain strong grassroots networks, committed supporters, and an ideological base. When the political environment changes, such a party can re-emerge quickly and demonstrate that it never truly disappeared.

Moreover, generational change plays a major role. A large portion of today’s voters belong to a new generation that does not carry the same lived memories of past political conflicts. They tend to focus more on current messaging, leadership style, and future promises.

This, Tanveer said, allows a previously sidelined party to be viewed through a fresh lens.

Also Read: Bangladesh polls: Around 70% ‘yes’ votes for July Charter referendum. What comes next

Indian subcontinent, political Islam & Jamaat

Jamaat-e-Islami, the parent outfit, was born in British India, driven by Maududi’s conviction that Islam was not merely a religion but a political system. After Partition, the organisation split into two separate entities: Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan and Jamaat-e-Islami Hind.

A branch would later emerge in Bangladesh.

In India, Jamaat’s Jammu and Kashmir wing was banned in 2019 in the aftermath of the Pulwama terror attack. In Russia too, the broader movement was designated a terrorist organisation in 2003 over alleged ties to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Afghanistan also has a branch, founded in 1972 by Burhanuddin Rabbani who drew inspiration from Maududi. Initially dominated by ethnic Tajiks, the Jamiat-e-Islami in Afghanistan became one of the principal factions within the “Peshawar Seven,” the coalition of Afghan mujahideen groups that fought Soviet forces during the 1980s.

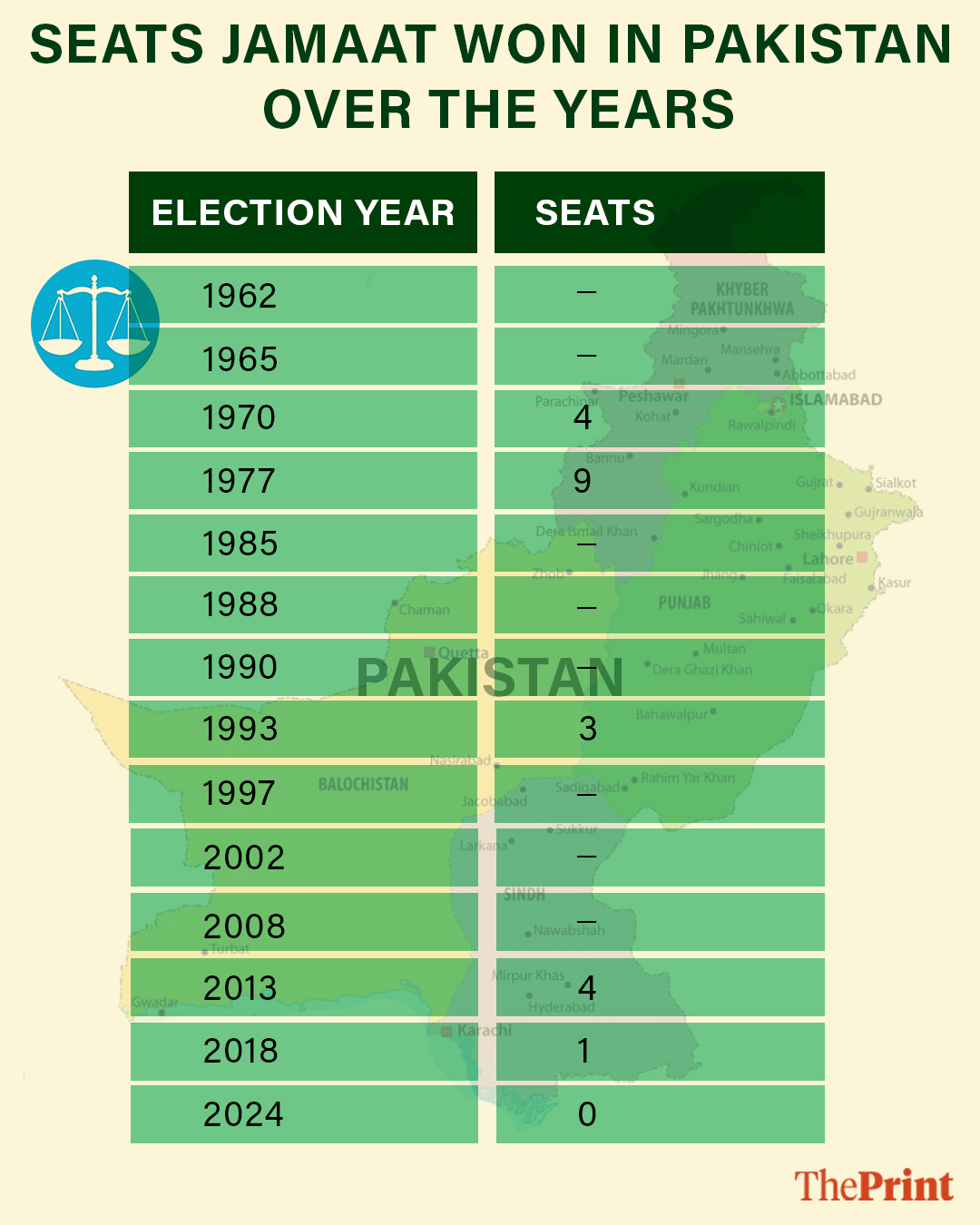

In Pakistan, Jamaat sought to transform the country into an explicitly Islamic state, but its electoral success has remained limited. In 1970, it fielded 151 candidates in the general election but won only 4 National Assembly seats.

In 1977, it won 9 seats as part of the Pakistan National Alliance. Its most significant electoral breakthrough came in 2002, when it joined the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal alliance, which won 59 seats and power in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Since then, its footprint has only shrunk: 4 seats in 2013, 1 seat in 2018 and no seats in 2024.

Even today, in Pakistan’s fragmented religious political landscape which includes figures like Fazlur Rahman, no single Islamist party commands a dominant nationwide mandate.

Pakistani journalist Ebad Ahmed said this is because of a paradox.

Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan traces its intellectual foundations to Maududi, whose vision of political Islam has had a deep and lasting influence in Pakistan. But Maududi initially opposed the creation of Pakistan, arguing that nationalism was not the basis for an Islamic state. He was also particularly critical of the Muslim League, which he viewed as a political outfit dominated by landlords and elites rather than religious leaders.

“Yet after Pakistan’s creation, Jamaat’s ideological influence steadily grew. The Objective Resolution of 1949, which laid the foundation for Pakistan’s constitution to be Islamic in character, reflected many themes central to Jamaat’s worldview. Over time, the party’s ideological framework shaped debates around Islamisation, education, defense narratives and state institutions,” said Ahmed. He told ThePrint that even groups that oppose Jamaat often operate within an Islamic ideological vocabulary that Maududi helped systematise.

Jamaat’s student wing, Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba, too has historically had an ideological presence on college campuses, but many of its activists eventually join mainstream parties.

Moreover, political dynamics differ in each of Pakistan’s four provinces. For instance, Jamaat never gained a foothold in Balochistan where local nationalism and tribal politics dominate. And in Pakistan’s Punjab province, Jamaat works more as a welfare and relief organisation, while Pakistan Muslim League (N) and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) dominate politics.

In Sindh, Jamaat’s primary base is urban Karachi, particularly among Urdu-speaking Muhajirs. Its cadre structure there is disciplined and organised. The current emir of Jamat-e-Islami Pakistan, Hafiz Naeem ur Rehman, has tried to position the party as a credible urban alternative. Despite visible electoral strength, Jamaat has struggled to convert support into executive power, even failing to secure the Karachi mayoralty at crucial moments. Interior Sindh, meanwhile, largely remains outside its grasp.

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Jamaat has pockets of influence, but larger movements, particularly the Imran Khan-led PTI, have cut into its support base. Another key factor here is women’s participation. In earlier decades, women were discouraged from voting in conservative areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which is not the case anymore.

A tactical rebranding

At the heart of Jamaat’s electoral success in Bangladesh is its emir, Dr Shafiqur Rahman.

Elected to lead the party by its rukon (full members) in 2019, he was reelected in 2023 and again in 2025. Shafiqur has been credited within the party for moving Jamaat away from its traditional insularity, opening its ranks to a wider array of politicians, courting religious minorities, and reaching out symbolically to freedom fighters—a political constituency long hostile to the party owing to its stance on the liberation of Bangladesh in 1971.

This general election marked another personal milestone for Shafiqur: he won his maiden parliamentary seat, that too in Dhaka, where Jamaat had never won a seat before.

Alongside him, Mia Golam Parwar, the party’s secretary-general since 2019, oversaw organisational expansion, while the student wing, Bangladesh Islami Chhatra Shibir, expanded its influence across campuses, feeding a younger cadre into national politics.

However, the organisation remains sceptical of core political principles such as secularism and democracy to such an extent that they continue to term these concepts to be ‘haram’ (‘forbidden’ in Islam).

Jamaat spokesperson Nakibur Rahman told ThePrint, “With 77 seats [allies’ tally], we have nearly quadrupled our parliamentary presence and become one of the strongest opposition blocs in modern Bangladeshi politics. That is not a setback. That is a foundation.”

If Jamaat’s electoral breakthrough marks a turning point, its leadership’s rhetoric points to a bid at regional repositioning. Over the past few days, Shafiqur or his party members never once mentioned Pakistan, instead speaking of a collaborative approach towards all.

In October 2025, speaking in New York, Shafiqur articulated what he described as a pragmatic vision of Bangladesh-India ties. “If we get the opportunity to govern the country, our relationship with India will be based on mutual respect,” he said. The 67-year-old added, “People can change their place of residence, but they cannot change their neighbours. We want to respect our neighbour, and we expect the same respect in return.”

He acknowledged that in terms of area, India is “26 times larger than Bangladesh” and has greater resources and manpower. “We respect them considering their position. However, they must also respect the existence of our small territory and its nearly 180 million people. This is our demand. If this happens, both neighbours will not only live well but will also bring mutual honor in the global arena,” he said.

The message was consistent. At a meet-and-greet with foreign journalists on the eve of the election, Shafiqur again described India as a “top priority”.

Among all major parties, Jamaat’s manifesto was the only one that explicitly mentioned ties with India and called for cordial relations.

As Shahan summed it up: “Jamaat will keep its anti-India rhetoric alive as an Opposition. A common narrative suggests Jamaat operates at Pakistan’s behest. Yet many ordinary voters in Bangladesh do not frame their support in India-Pakistan terms.”

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: BNP’s resurgence in Bangladesh: Tarique’s liberal pivot, Jamaat fears & politics of limited options