New Delhi: Pakistan’s Chief of the Army Staff (COAS) Field Marshal Asim Munir is just one step away from becoming the most powerful man in his country, officially. Six months after Operation Sindoor, Pakistan tabled the 27th Constitutional Amendment in the Senate, effectively giving lifetime status and constitutional protection to Munir apart from handing him unilateral command of the armed forces.

Officials have cited this promotion only the second (after 1959, when Ayub Khan was made Field Marshal) in Pakistan’s history as justification for formally recognising such lifetime ranks in law.

If enacted, the amendment would also abolish the office of the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee on 27 November, the day the current CJCSC General Sahir Shamshad Mirza is scheduled to retire. His departure would mark the end of the Joint Services Committee, making him the last officer to hold the position.

This is effectively one of the most far-reaching restructurings of Pakistan’s governance framework in decades, overhauling the judiciary, redefining military ranks, and expanding executive powers.

The draft amendment, circulated among lawmakers this week, seeks to create a new Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) that would assume many of the powers currently held by the Supreme Court, including the authority to hear constitutional petitions and disputes between governments.

Law Minister Azam Nazeer Tarar tabled the 26-page draft to be titled the bill for Constitution (Twenty-Seventh Amendment) Act, 2025, hours after it received the federal cabinet’s approval.

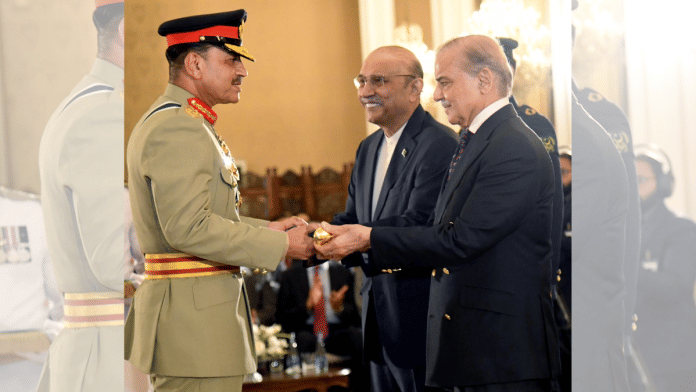

The cabinet meeting, chaired by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, was held via video link from Baku, where he was attending Azerbaijan’s Victory Day ceremony alongside Field Marshal Munir.

Like last time, both the senate proceedings are being done over the weekend which is not the usual norm. The meeting was boycotted by Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F) and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) lawmakers.

While the Opposition staged a boycott, a joint meeting of the Senate and the National Assembly’s law and justice standing committees on Sunday approved the 27th Constitutional Amendment Bill with minor changes, The Dawn reported.

On Sunday, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif ordered the withdrawal of a proposed clause granting immunity to the PM in the 27th Constitutional Amendment, saying the premier must remain “fully accountable before the law and the people.”

Taking to ‘X’, Sharif clarified that the clause was not part of the cabinet-approved draft and directed its immediate removal. “While I acknowledge their intent in good faith, the proposal was not part of the Cabinet-approved draft. I have instructed that it be withdrawn immediately,” he wrote.

On my return from Azerbaijan, I have learnt that some Senators belonging to our party have submitted an amendment regarding immunity for the Prime Minister.

While I acknowledge their intent in good faith, the proposal was not part of the Cabinet-approved draft. I have…

— Shehbaz Sharif (@CMShehbaz) November 9, 2025

The planned amendment comes a year after the controversial 26th Amendment curtailed judicial independence. It had stopped short of creating a second top court–the Federal Constitution Court (FCC)–to handle all cases related to constitutional powers. The move, had it gone through, would have limited the role of Pakistan’s Supreme Court into adjudicating civil and criminal disputes only.

Earlier this week, Shehbaz Sharif spent days courting coalition allies—including delegations from the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), Muttahida Qaumi Movement–Pakistan (MQM-P), and Pakistan Muslim League-Quaid (PML-Q)—to secure the two-thirds parliamentary majority required for passage of the Bill.

With 233 seats in the 336-member National Assembly, the ruling coalition has enough votes in the lower house but falls short in the 96-member Senate, where it holds 61 of the 64 seats needed to clear the Bill.

The opposition PTI has vowed to resist the changes “tooth and nail”, with its chairperson Gohar Ali Khan warning that the amendment would “jeopardise the independence of the judiciary” and threaten the federation’s integrity.

The government dismissed allegations that the amendment would undermine provincial powers or judicial independence. “No step will be taken that weakens the federation or the provinces,” Defence Minister Khawaja Asif insisted in a press conference last week.

But lawyers and analysts say the changes could tilt the balance of power, formalising what many already describe in the adage: “Every country has an army, whereas the Pakistani Army has a country.”

Also Read: Asim Munir now has a Musharraf-style path ahead in Pakistan. It’s the 27th Amendment

An unopposed military—and its rule

At the centre of the debate is Article 243 of Pakistan’s Constitution, the clause that defines who commands the armed forces and one for which the federal government and military are perpetually embroiled in a tug of war.

The proposed changes to Article 243 introduce a significant restructuring of Pakistan’s military command framework. As per the amendment, the President shall, on the advice of the Prime Minister, appoint the Chief of the Army Staff, who shall also serve concurrently as the Chief of the Defence Forces; the Chief of the Naval Staff; and the Chief of the Air Staff

The position of Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee is to be abolished and the ranks of Field Marshal, Marshal of the Air Force, and Admiral of the Fleet would be granted lifetime status and constitutional protection.

These changes collectively consolidate command under the Army Chief—who will simultaneously act as the Chief of the Defence Forces—and redefine Pakistan’s top military structure following the abolition of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee.

These titles — reserved for exceptional national heroes — could not be revoked except under charges and procedures outlined in Article 47, which governs the removal of the President.

“Field Marshal, Marshal of the Air Force and Admiral of the Fleet, being national heroes, shall not be removed from office except on the ground or charges and in the manner provided under Article 47 (9). The provisions of Article 248, as applicable to the President, shall mutatis mutandis apply to Field Marshal, Marshal of the Air Force and Admiral of the Fleet,” the Bill reads.

Their salaries, allowances, and post-command duties would be determined by the President on the advice of the Prime Minister.

Article 47 of the Pakistani Constitution outlines the procedure for the removal of the President, allowing for impeachment on grounds of physical or mental incapacity, or for violating the constitution, or gross misconduct. This process requires a written notice from at least half the members of either house of Parliament, which is then sent to the National Assembly Speaker, and culminates in a joint sitting of both Houses to pass a resolution for removal with a two-thirds majority.

On the possibility that Article 243 may be amended, Pakistani journalist Zarrar Khuhro said on ‘X’ that the clause has been changed five times since 1973, when the Constitution was adopted.

The original version said, “The federal government shall have control and command of the armed forces.” But, in 1985, General Zia-ul-Haq changed it, so “the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces shall vest in the President”. Through the 8th Amendment, he also gave the President power to appoint service chiefs “at his discretion”, sidelining the Prime Minister.

Nawaz Sharif’s 13th Amendment in 1997 removed “in his discretion”, returning power to the PM. General Pervez Musharraf reversed this in 2002 and changed the language to “in consultation with the Prime Minister”—making the President’s word final.

The 18th Amendment in 2018 then clarified that military appointments are made on the PM’s advice, effectively reducing the President’s role to a ceremonial “supreme commander”.

Law Minister Tarar said the post of Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee would be abolished on 27 November. After that, the Army Chief would also serve as Chief of Defence Forces, while the Prime Minister, on his recommendation, would appoint the Commander of the National Strategic Command.

The 26th Amendment had increased the Army chief’s term to five years, extendable for another five, but the current chief was appointed under the old three-year rule. This created some legal confusion, with some arguing that last year’s amendment automatically extends Munir’s term to five years while others say that a fresh notification is needed to make it official.

Minister of State for Law and Justice Aqeel Malik told reporters that a new notification for the army chief’s tenure was unnecessary, as the Army Act—amended through the 26th Constitutional Amendment—already sets a five-year term for the position.

“Article 243 was meant to preserve civilian command over the armed forces. The 27th Amendment risks rewriting it into a charter of military supremacy,” The Dawn wrote in its analysis.

Stripping the Supreme Court

On the creation of the Federal Constitutional Court, Tarar said it was rooted in the 2006 Charter of Democracy between the PPP and the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N). The new court, he explained, would handle constitutional matters with representation from all provinces, while existing superior courts would continue hearing other cases.

He noted that previous efforts, such as forming constitutional benches, had apparently failed to ease the Supreme Court’s backlog, with only 5–6 percent of cases consuming nearly 40 percent of the court’s time.

Under the proposal, the FCC would become Pakistan’s highest authority on constitutional matters, effectively stripping the Supreme Court of its original jurisdiction under Article 184–the provision that grants the Court suo motu powers to take up matters of public importance and fundamental rights.

The move would establish a dual-apex system, with the FCC handling constitutional interpretation and intergovernmental disputes, while the Supreme Court would remain the country’s top appellate body for civil and criminal cases.

Judicial appointments to both courts would be made through a restructured Judicial Commission, which would include the Chief Justices of both the FCC and the Supreme Court. The amendment raises the retirement age of FCC judges to 68, while fixing the Chief Justice of the FCC’s term at three years.

Last year’s 26th Amendment gave the Pakistan government a lot more control over the judiciary. Yasser Kureshi, lawyer and lecturer for South Asia studies at the University of Oxford, wrote in an article that the judicial amendments introduced in 2024 worked as 3Cs— court-packing, court-curbing and court-managing.

Court-packing, he wrote, allowed insertion of judges who were loyal to the government. Instead of the senior-most judge being appointed the Chief Justice, a parliamentary committee controlled by the ruling coalition gets to pick the CJ.

Court-curbing limited SC’s powers. Judges can no longer take up suo-motu (on its own) cases, he said.

And court-managing led to creation of constitutional benches within the Supreme Court as a compromise after the proposal for a FCC was dropped due to opposition. Members of these constitutional benches, Kureshi wrote, are selected by a judicial commission that is dominated by government faithfuls.

The centrepiece of the 27th Amendment, lawyers believe, is the unfinished task of forming the FCC.

Pakistan’s legal system is built on the tradition of common law, inherited from colonial rule, under which independent judges interpret laws through precedents. Barrister Asad Rahim Khan argued in a news article that this system was designed to “shield the citizen from tyrannical kings (a recurring problem in Pakistan).”

The idea of a separate constitutional court isn’t new to Pakistan. The country had a Federal Court till 1956, after which it became the Supreme Court. Now, the government wants to split it again, lawyers say.

They say that if the amendment goes through, the Supreme Court would retain routine civil, land and property disputes and criminal cases, while all constitutional matters, including fundamental rights challenges and review of government actions, would move to the FCC.

“Last time (26th Amendment), they proposed a constitutional court, but coalition partners opposed it. So, they agreed to form a constitutional bench. This time, a similar proposal is reportedly under consideration … If this happens, some powers of the Supreme Court will be shifted to the new court,” Adil Chattha, a lawyer at the Islamabad high court, told ThePrint.

Supporters of the FCC say that the new court would reduce case backlog.

On this, barrister Yaseer Latif Hamdani told ThePrint he supports the concept but remains cautious of executive control over judicial transfers. “I happen to agree with the proposition that Pakistan needs the FCC. The transfer of judges, however, is problematic and may lead to a pliant judiciary,” he said, referring to the previous amendment of shifting of judges.

But Khan pointed out in the article that official data shows the Supreme Court’s pending cases constitute only 2 percent of all cases yet to be adjudicated; 98 percent of them were in lower courts.

“Constitutional benches created by the 26th Amendment have already issued confusing and contradictory judgments,” Khan wrote, noting that decisions on reserved seats and military trials “seemed to ignore basic legal logic and constitutional rights”.

“Pakistan has never suffered from a shortage of constitutional courts—what has forever plagued it is a lack of constitutional courage,” he wrote.

The amendment also proposes changes to Article 248, granting the president lifetime immunity from criminal prosecution or arrest—a privilege that would continue for governors only while in office. Currently, both offices enjoy such protection solely during their respective terms.

Addressing the issue of Senate elections, Tarar noted that polls in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa had been delayed for over a year. To prevent similar disputes in the future, the law minister said, the Bill includes a clarifying clause outlining procedures for electing the Senate chairman and deputy chairman immediately after elections.

Additionally, the draft seeks to increase the constitutional cap on provincial cabinet sizes, raising the limit from 11 percent to 13 percent of each assembly’s total membership.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Pakistan Army’s FWO and NLC are the business empires that will benefit from Trump proximity

Hitting soft is a sin. Modi did that & Munir rose in power.

modiji obliged asim munir by ordering operation sindoor – what a trap sir ji