US President Donald Trump has said he’s instructed the Defense Department to start testing nuclear weapons “on an equal basis” with rivals such as Russia and China.

It’s unclear whether he means detonating nuclear warheads, which would reverse decades of American policy and violate a de facto global ban, or a scale-up of something the country already does: testing weapons delivery systems, such as intercontinental ballistic missiles, that can carry nuclear warheads.

A return to explosive nuclear testing isn’t a new idea in Trump’s orbit. Senior officials reportedly considered the move during his first term in office, and last summer, Robert O’Brien, who served as Trump’s national security adviser from 2019 to 2021, made a public push for the US to resume full-scale live tests to “maintain technical and numerical superiority” over Russia and China’s combined nuclear stockpiles.

Trump has framed his new directive as a response to other nations’ testing programs. His comments followed Russia announcing successful trials of a cruise missile and torpedo drone, both of which are capable of carrying a nuclear warhead and run on atomic energy. Neither test involved a nuclear explosion.

When did the US last conduct test detonations of its nuclear weapons?

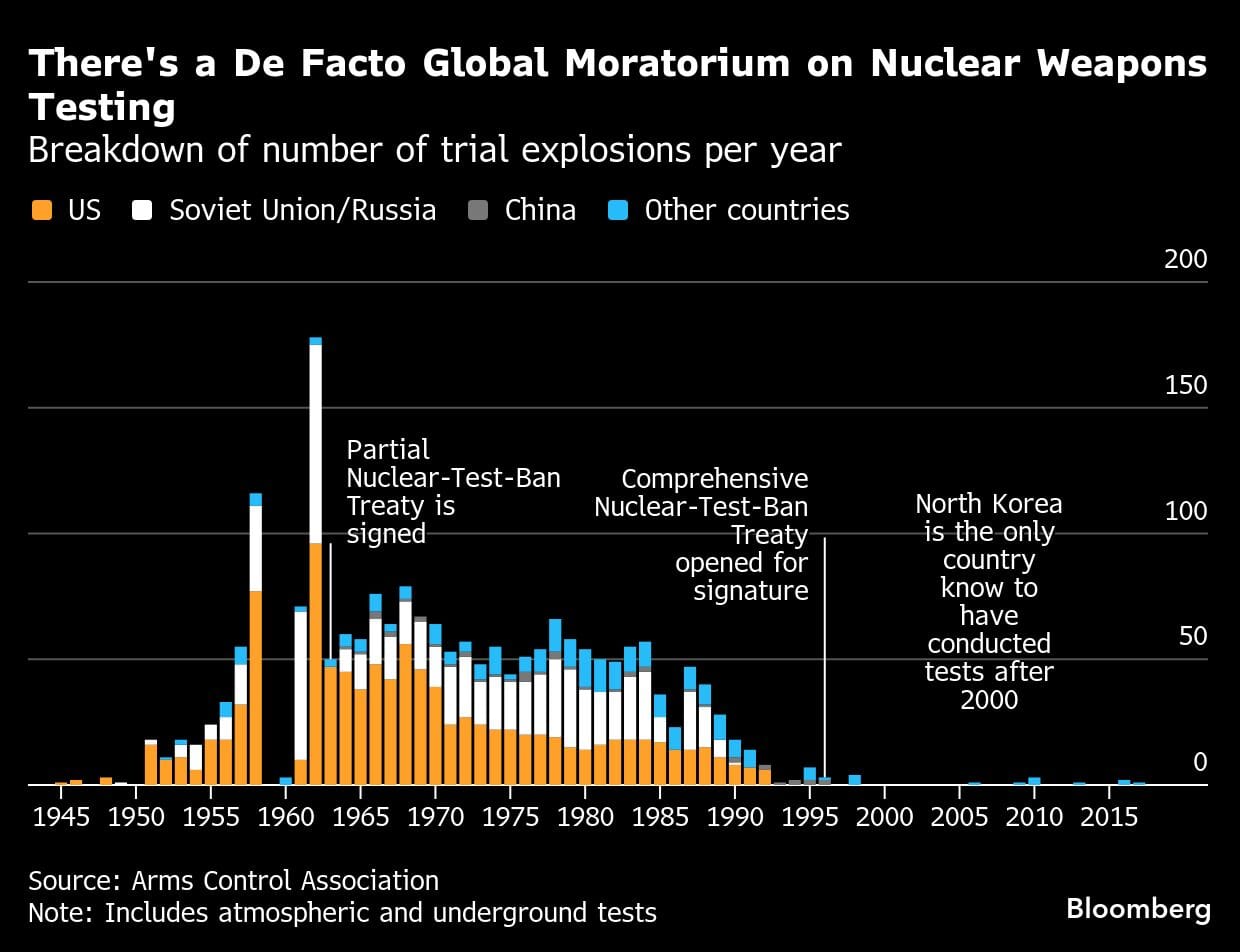

The US hasn’t tested the explosion of a nuclear weapon since 1992, when then-President George H.W. Bush ordered a moratorium. It instead relies on proven designs, advanced computer simulations and so-called subcritical experiments that stop short of detonating a warhead.

Russia’s last known nuclear test detonation was also more than 30 years ago, in 1990, while China’s was in 1996. Together with the US, they’re signatories to an international agreement banning nuclear weapons tests: the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, which was negotiated in the early 1990s and made open for signature in 1996.

While none of the trio have ratified the deal, meaning it technically hasn’t entered into force, they still observe its terms — as do nuclear-armed states such as India and Pakistan that haven’t signed the treaty. The only nation known to have tested nuclear warhead designs this century is North Korea, which last detonated a device in 2017.

Are live tests of nuclear weapons necessary?

Nuclear devices require precise timing, temperature, pressure and materials. During their early development, physical testing helped scientists understand these different variables, as well as how much damage the weapons can inflict on a target and the levels of radiation and heat they produce.

The first test detonation was conducted in the New Mexico desert in 1945 as part of the Manhattan Project. This preceded the Americans dropping atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II.

For decades afterward, developers around the world used remote testing sites to determine whether new designs worked and could deliver the expected amount of explosive power. Aside from providing technical data, the demonstrations were also seen as a projection of military strength.

The most modern US nuclear weapon is the B61-13 air-dropped bomb. The B61 series dates back to the 1960s and was updated over the decades through additional testing. But technological advancements mean the latest iteration was developed using computer simulations and data from previous tests, without a live test explosion.

A return to full-scale nuclear detonation testing in the US would take several years and cost hundreds of millions of dollars, said Daryl G. Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association.

What risks could come with a restart of nuclear weapons testing?

Should the US resume testing activity, it could potentially trigger another nuclear arms race — and not just among superpowers — undermining decades of non-proliferation initiatives. Russia has said that if the US defies the global ban, it will “act accordingly.”

Trump’s cryptic comments about testing come at a precarious time for nuclear diplomacy and contradict his previous calls for denuclearization. The New START Treaty between the US and Russia, which limits their numbers of deployed strategic warheads, is due to expire in February.

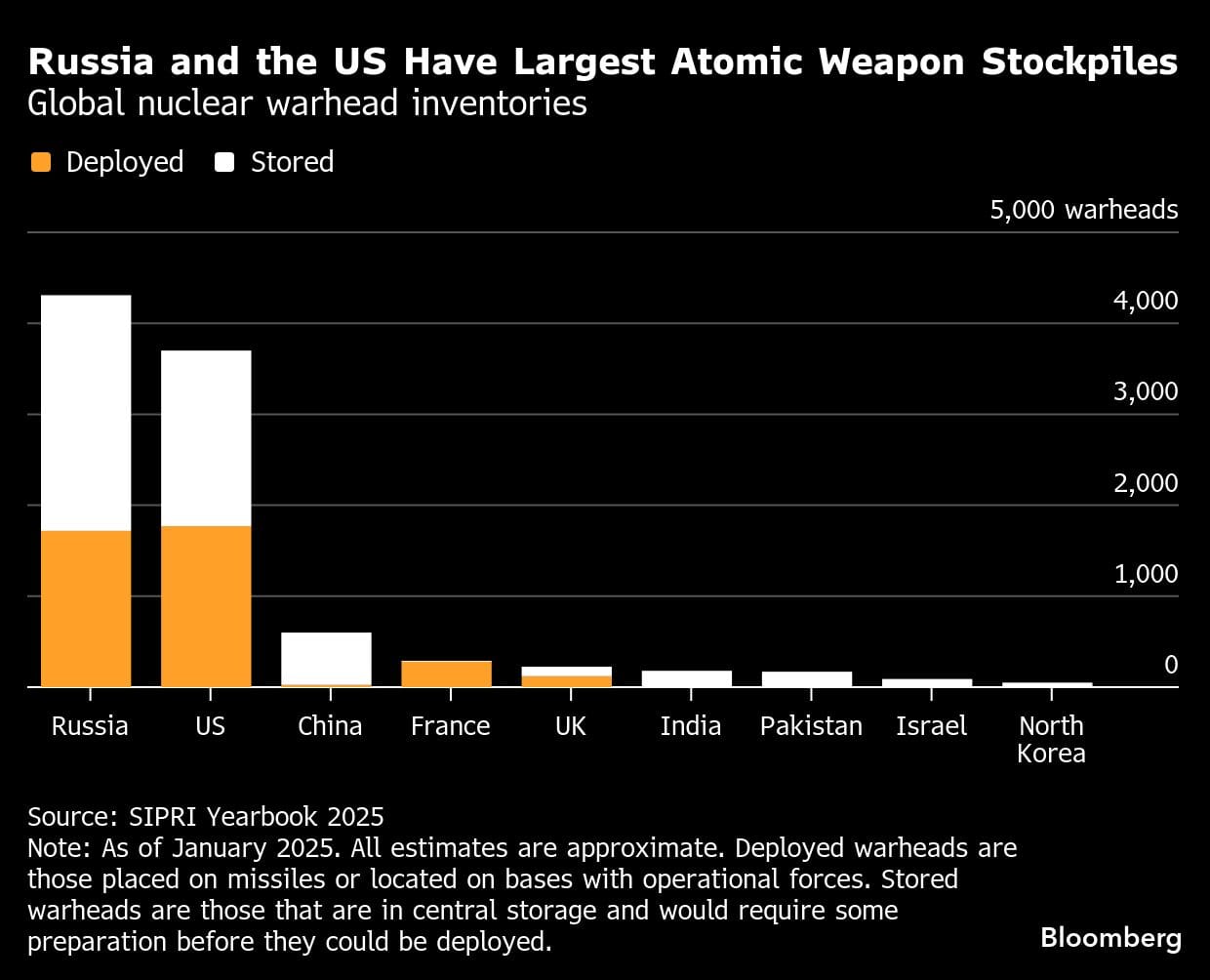

Russia has the world’s largest stockpile of nuclear weapons, with about 4,300 deployed and stored warheads, followed by the US, whose inventory stands at 3,700, according to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. China is a distant third, possessing 600 warheads, although US intelligence has warned that the country is rapidly expanding that arsenal.

Who would benefit from a resumption of nuclear weapons testing?

Annual assessments conducted by directors of the US national nuclear laboratories and the commander of US Strategic Command say the country’s nuclear stockpile is safe, reliable and effective, and there’s no technical reason to return to explosive testing.

Between them, the US and Russia carried out nearly 2,000 nuclear weapons tests from the 1940s to 1990s and have enormous amounts of data to work with already, said William Alberque, a Europe-based senior fellow at the Pacific Forum. If the US were to revive its testing activity, this would “open the door for China to resume testing, and they’re the only one of the Big Five that has a need for new test data.”

The Big Five refers to countries officially recognized as nuclear-armed states under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons: Russia, the US, China, France and the UK.

Three other states — India, Pakistan and North Korea — acknowledge having nuclear weapons; Israel is widely believed to have them as well but has never confirmed or denied its arsenal.

How were nuclear weapons tested in the past?

The earliest tests were carried out in the open air, either detonated on towers over land or dropped from aircraft. These atmospheric tests produced valuable information about the weapons, such as the size of the “fireball” of extremely hot, rapidly expanding gas, and the amount of radioactive fallout generated by the blast.

But there were serious environmental and public health dangers, particularly as wind and rain spread radioactive particles to populated areas. The Castle Bravo test on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands in 1954 was the largest test detonation conducted by the US, producing more than double the expected explosive power. It was also the worst radioactive disaster in American testing history as the fallout contaminated a much wider area than anticipated.

Mounting safety concerns culminated in the international Partial Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty in 1963, which prohibited above-ground and underwater testing. The last atmospheric US and Russian tests were in 1962, while for China, which didn’t sign this treaty, its final test was in 1980.

Underground testing was mostly conducted by excavating a cavity deep below the surface and detonating the warhead in the middle of that space to contain the heat, pressure and fallout. This method also offers more secrecy, making it more difficult for adversaries to analyze the fireball.

While safer than atmospheric testing, the underground setting still carried the risk of soil and groundwater contamination There also were some accidents, such as during France’s Beryl test in Algeria in 1962, when hot gases and radioactive material spewed from the side of the mountain where the trial took place.

What’s the concern about the weapons Russia has been testing recently?

The 9M730 Burevestnik cruise missile is capable of carrying a nuclear warhead and is powered by an atomic reactor, relying on a fission reaction — the splitting of atoms to release energy — as the core of a ramjet. This gives the missile nearly unlimited range. In October, Russia said the Burevestnik had successfully test flown for about 15 hours, covering around 14,000 kilometers (8,699 miles).

Although the Russians designed the weapon to bypass air and missile defenses, it’s not clear whether the Burevestnik is any more capable of doing that than conventional cruise missiles, according to Jeffrey Lewis, a nuclear arms expert at the Middlebury Institute of Strategic Studies in California.

The US has sensitive satellites in geostationary orbit that form the Space-Based Infrared System that can detect missile launches anywhere on Earth, as well as conventional air defenses designed to shoot down cruise missiles. This year, Trump directed the US military to develop and deploy the Golden Dome system, which is meant to defeat any aerial threat against the country.

“This is ultimately what is so stupid about arms races,” Lewis said. “There isn’t any victory at the end. It’s just a process of one side building systems, the other side building systems in response, and so on. Everyone ends up in exactly the same place they started, just at great expense.”

(Reporting by Gerry Doyle)

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.