New Delhi: President Donald Trump announced a temporary 10 percent global tariff under Section 122 of the Trade Act—effective 24 February—hours after the US Supreme Court struck down his sweeping global duties imposed under emergency powers.

In the latest development, Trump, on 21 February, decided on an increased 15 percent tariff under Section 122—“effective immediately”—and communicated it via Truth Social.

The US Supreme Court had invalidated the tariffs imposed under the 1977 IEEPA only, holding that the law does not explicitly authorise broad tariff powers, which the Constitution reserves for Congress.

To maintain tariff policy momentum despite the ruling of the highest US court, the Trump administration plans on relying on Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974.

The provision allows the US President to impose temporary import duties of up to 15 percent to address “large and serious” balance-of-payments deficits. Unlike IEEPA, which does not explicitly mention tariffs, Section 122 explicitly authorises temporary, across-the-board tariffs for a limited 150-day period, unless Congress votes to extend them.

During the 10 percent tariff announcement, the Trump administration had emphasised that other tariff measures, such as those under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962—used earlier in 2025 to hike the tariff on steel and aluminium from Mexico, Canada, India, and the European Union countries to 50 percent—remain in “full force”. The 25 percent tariff on auto parts, earlier imposed on the same countries under the same section, would also prevail.

Besides, tariffs of up to 50 percent on Chinese goods—which came into force in 2025 under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974—are still in force, added the US administration. Section 301 provides for tariffs in cases of unfair foreign trade practices, including intellectual property theft and forced technology transfers.

Section 232 (national security) and Section 301 (unfair trade practices) do not rely on the now-struck down IEEPA.

What do these announcements mean for India? Though the court’s ruling effectively lowered the immediate tariff burden for some Indian exporters by restoring the most favoured nation rates (MFN), the tariffs on steel, among other goods under Section 232, continue. Now, Trump’s new 15 percent tariff would apply to the remaining exports—which got court relief—as a surcharge on top of the existing, product-specific MFNs. This tariff, though, is uniform and brings all countries at the same tariff level.

Notably, the India-US interim trade agreement reached earlier in February had fixed the reciprocal tariff for labour-intensive industries, such as textiles and apparel, leather and footwear, plastics and rubber, organic chemicals, home décor and artisanal goods, as well as certain machinery, to 18 percent, down from a peak of 50 percent in 2025. More significantly, the tariffs on these industries in other neighbouring countries were higher.

Under the same agreement, the US had agreed to remove Section 232 tariffs on certain aircraft and aircraft parts and to provide a preferential tariff-rate quota for auto parts.

Since the court order, calls for looking at the deal again have been growing louder in India—18 percent doesn’t sound as beneficial against the backdrop of the roughly same global rate (15 percent plus MFN).

This comes as Trump’s new 15 percent tariff faces a 24 July Congressional test—the process begins earlier. The tariff is unlikely to be extended, say some reports, citing the upcoming, November mid-term elections, in which instance it will simply lapse.

A key feature of Section 122 is that it cannot be used for targeting specific countries, say, by citing the fentanyl crisis or Russian oil, and cannot be used as a punitive measure. At the same time, it takes away the competitive edge of securing any early deal with the US.

Section 122, which reportedly has never been used to impose trade restrictions, could, eventually, remain Trump’s short-term negotiating leverage, according to legal experts.

Also Read: US SC strikes down Trump tariffs, calls it beyond his legitimate reach

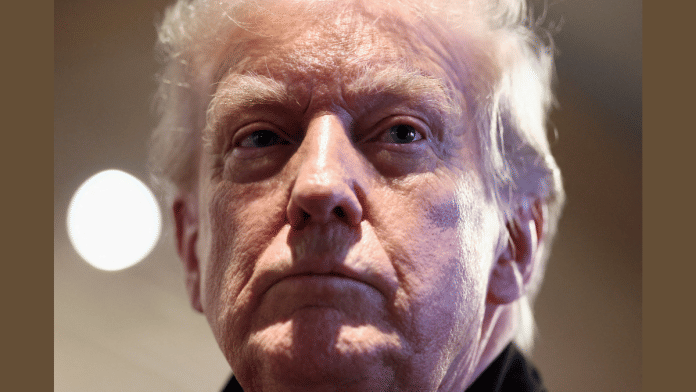

Trump’s sharp criticism

At a White House press conference following the judgment, Trump sharply criticised the majority of justices. He called the ruling “deeply disappointing” and accused the court of undermining executive authority in matters of trade and foreign policy.

The President lashed out at the bench, including the two judges he had appointed during his first term, accusing them of lacking the courage to “do the right thing”. He insisted that his administration would continue using every available legal instrument to protect American industries and workers.

Trump framed the court’s intervention as a setback but not a defeat, arguing that Congress already provided sufficient statutory tools to continue his tariff agenda through alternative provisions.

What the court held

In its 6–3 ruling, the US Supreme Court concluded that the **International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) does not authorise the President to impose tariffs. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts said that while IEEPA grants the executive broad powers to regulate financial transactions during emergencies, it does not extend to levying import duties.

The opinion underscored the importance of Article I, Section 8 of the US Constitution, which assigns specific legislative powers to Congress, including the authority to lay and collect taxes, regulate interstate and foreign commerce, coin money, declare war, and raise armies.

The court noted that IEEPA lists powers such as blocking transactions and freezing assets, but is silent on tariffs, a silence that the majority found decisive.

The bench also observed that no President in IEEPA’s nearly five-decade history had used it to impose sweeping global tariffs of this scale.

However, in dissent, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, argued that the authority to regulate importation has historically encompassed tariff-setting powers. The dissent warned that the decision could complicate trade enforcement and create administrative disruption.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: Neal Katyal’s big win: The Indian-American lawyer who took on Donald Trump’s tariffs head on